Stanislaw Marian Thun,

born in 1894 in Dzierzno Dworskie near Rypin

soldier of the Home Army, lieutenant colonel, noms de guerre: "Leszcz", "Janusz", "Malcz", "Nawrot"

killed in action on 3 August 1944

Warsaw Uprising Insurgents' Biographies

Stanislaw, Jerzy i Wanda Thun

The von Thuns, a noble family from Pomerania, have on numerous occasions proven their patriotism and devotion to the Polish tradition.

The great-grandfather, Julian, fought in the January Uprising. The grandfather, Stanislaw, fought in WWI and the Polish-Bolshevik War. He also fought in the 1939 Defensive War, and was a member of KeDyw (Kierownictwo Dywersji - Home Army Sabotage Command). He was killed during the Warsaw Uprising.

His son Jerzy joined the Home Army while still in his teens. He took part in the Warsaw Uprising.

Jerzy's future wife, Wanda Pienkowska, also fought in the Warsaw Uprising. She was a Home Army soldier and a combat medic. Althought they both fought in the same area, just a few blocks apart, it was not until after the war that they met for the first time in Gdansk.

Stanislaw Marian Thun

Stanislaw Marian Thun  Jerzy Thun

Jerzy Thun Wanda Thun

Wanda Thun

MY GRANDFATHER - STANISLAW

Stanislaw Marian Thun was born on 19 November 1894 in Dzierzno Dworskie in Swiedziebna parish near Rypin. He could be described as a paragon of virtue. He lived life to the fullest, and his broad interests and numerous achievements would be enough to fill at least two ordinary biographies. A steadfast patriot, he was known for his integrity and diligence for which he received numerous commendations from his army superiors. He spoke three foreign languages: German, Russian and French. He often visited Vienna, travelled extensively in Russia and North Hungary, visited Romania. Many traits of his character, including aptitude for languages and personal integrity, were inherited by my father.

In June 1913 my grandfather graduated from the Third Gymnasium in Cracow and passed his matura exam [a rough equivalent of the British A-levels - translator's note]. In the autumn of the same year he entered the Medical School at the Jagiellonian University, but he had to leave having completed only two semesters (student's book No.: 13041).

After the outbreak of WWI, on 16 August 1914 Stanislaw enlisted in the Polish Legions (sworn in on 04 September 1914). He received a frontline assignment and took part in the Carpathian Campaign. Already on 29 September 1914, upon the recommendation of brigadier Zygmunt Zielinski, he received a battlefield commission to the rank of ensign (promotion certificate issued on 19 January 1916).

First, he served as a platoon commander in the 2nd Infantry Regiment of the Polish Legions, and then as an aide-de-camp in the 2nd Batallion, 2nd Infantry Regiment of the Polish Legions. On 29 October 1914, his unit, under the command of Gen. Z Zielinski, took part in the battle of Nowodworna near Molodkowa and Harcz, in which about 700 soldiers were killed. The grandfather was wounded in the right leg - he walked wih a limp for the rest of his life - and spent the next several months in a Russian hospital in Ploskirow (together with Capt. Tadeusz Tesler). After his wounds had healed up he was taken prisoner by the Russians.

In the meantime his military unit command issued a Diploma (No.: 1270). The little piece of coloured parchment reads:

To the fellow soldier, Ensign Stanislaw Thun, for conspicuous gallantry and to commemorate the combat service

with the 4th Infantry Regiment of the Polish Legions during 1915 to 1916, we hereby present the Swastika Award, 2nd class.

Issued near Ruda Sitowicka the command of the 4th Inf. Reg.

In the third year of the World War ROJA

16 September 1916

The diploma must have been sent to my great-grandmother, because her son was a prisoner of war at the time.

In June 1917, he managed to escape using a forged document of identity bearing a false name of Malczewski. Russian documents indicate that my grandfather may have been kept in a forced labour camp (Katorzhennaya rabota) in Irkutsk. After the escape he had been wandering through Russia until 02 February 1918 when he crossed the front line and was interned in Vienna.

After he had returned to Cracow he started working as a clerk in the Welfare Inspectorate of the Centre for Economic Restoration of the Imperial and Royal Stewardship. His employment was confirmed by a certificate issued on 18 April 1918, which entitled the holder to stay in the office after regular working hours. On 1 November of the same year he enlisted in the Polish Army.

For the first month of his service he was an adjutant officer in the rank of 2nd lieutenant. On 12 November he was promoted to 1st lieutenant. His promotion was announced in the general order No. 8 issued by Brig. Gen. Roja. He was next assigned to the 4th Infantry Regiment as the commander of the unit's army messengers. In January 1919 he became an aide-de-camp to the commander of Warsaw Military District, and after that he served for five months as a company commander in the 2nd Infantry Division of the Polish Legions stationed in Jablonna. Next, he received a frontline assignment to the 2nd Infantry Division, in which he served as a company and batallion commander. There is a military ID preserved in the family archive issued on 21 May 1919 in Lida by the command of the 2nd Division of the Polish Legions, and signed by Gen. Roja. It states that the holder, Lt. Thun Stanislaw, was assigned to the 2nd Division of the Polish Legions as the commander of the Rover Scout Military Unit. Before long, the 1st Rover Scout Comapany under my grandfather's command distinguished itself in battle and earned a citation in the order No. 108 issued by Gen. Roja on 27 July 1919. The order included also several valor awards citations. The order reads:

The Gallant soldiers of the 1st Rover Scout Company under the exemplary leadership of their valiant commander Lt Thun have distinguished themselves in action during the fights near Radoszkowice, Rogowaja and Puchalki. Under heavy artillery fire, outnumbered by the advancing forces of the enemy, the company held its position repeatedly forcing the enemy to withdraw.

The gallantry demonstrated by the rovers at Radoszkowice as well as during the battle of Radziwce, in which they drove back the enemy charge, is even more commendable in the light of the fact that the company had volunteered to hold the exposed positions. The company commander and the following rovers-officers and soldiers are hereby awarded...

From September 1919 to March 1920 my grandfather served as an aide-the-camp: first to the CO of the Operational Group Kielce, and then to the commander of the Pomerania Group, and then to the commander of the 2nd Frontline Army.

I would like to quote the general order No. 2 of 6 September 1920:

Soldiers!

Each one of you has or had a mother!

"Certainly", you will say, "everyone has a mother".

Brothers in arms! Not every mother, however, is equally loving and caring. It may even happen that a mother hardly cares for her child.

"So it may be", you will say.

Fellow soldiers, even if your mother were the worst of all, would you stand and watch her being tyrannized and beaten by a stranger?

Soldiers! How can the Bolsheviks believe that we will let them beat our Mother Country - Poland, even though she had no time, and was even not allowed to rise her children properly under the yoke of the German and Russian rule? Fellow soldiers, the mind and the heart command us to stand and fight to defend ourselves against Moscow's aggression and the tsarist methods.

I salute you!

(-) ROJA, Gen.

The order is to be read in all units under my command.

I hereby certify that this is a true copy of the original

(-) Rosinski, Lt.Col.

It is interesting to note that all general orders from the period were signed only with surnames. I do not know whether it was just a military mannerism or some kind of a security measure.

On 23 October 1920 Stanislaw submitted a requested for a transfer to Warsaw so that he could take up studies at the College of Trade. The permission was granted and he was transferred in December 1920. While in Warsaw, he served as a liaison officer to Warsaw Military Command in the rank of captain. At the same time, he may have worked for the military intelligence. An identification document No. 13 issued in Grudziadz on 04 June 1920 to Stefan Tiedmann, a merchant, born on 20 May 1894 at 44 Lipowa Street, Grudziadz, which contained my grandfather's photograph, may suggest my grandfather's involvement with espionage.

Before he had earned his degree in June 1922 for a dissertation "Polish Immigrants in Parana After the World War", my grandfather was awarded the Silver Cross of the Order Virtuti Militari (the highest Polish military award for valor). The medal was awarded on 17 May 1922 by the Office of the Adjutant General to the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces.

The Virtuti Militari 5th class (the Silver Cross) award certificate

On 1 January 1923 he was assigned to the Military Research and Publishing Institute. On 15 February 1923 he became the head of the 2nd Department of the Scientific Publishing Institute.

From 1 September to 1 December 1924 he attended a pre-promotion upgrading and unification course for officers in Rembertow. His certificate of achievement was signed by Brig. Gen. Prich (again, no Christian name). He was promoted to major shortly after.

On 28 April 1926, the Chancellor of the Order Polonia Restituta signed a decree of the President of the Republic of Poland making Major Stanislaw Thun a Member of the Order for his meritorious contribution to military science and publishing.

Member of the Order Polonia Restituta award certificate

On Polish Independence Day, on 11 November 1928, my grandfather was awarded two medals: The War of 1918-1921 Commemorative Medal and The 10th Anniversary of Polish Independence Medal.

On April 8 1931, the Minister of Home Affairs Slawoj-Skladkowski awarded my grandfather the Lifesaving Medal for rescuing a drowning man on 15 June 1930.

All those honours were granted shortly before my grandfather had retired from active duty on 29 February 1932. After he had retired he became a director of the Central Miliary Bookshop, which position he held until 1939.

In the certificate of service issued by the director of the Military Research and Publishing Institute, Lt. Col. K. Ryzinski, my grandfather was described as a man who had been "diligent in fulfilling his duties". He was also characterized as an intelligent, hard-working and industrious man, full of initiative, independent, with an agile mind.

On 17 January 1939 he was awarded the Honorary Cross of Scout-Soldiers of the War of Independence for his participation in the scout movement between 1909 and 1921.

19 September, Praga. Animals are miserable. There are a lot of hungry, homeless dogs wandering blindly around. There are carcasses of dead horses lying everywhere in the streets. Cats, who used to be so well off, now walk around empty houses. Lazy out of hunger they lick the remains of food out of empty tins and gladly accept caresses. During heavy artillery fire, 2nd Lt. Czarnecki hides under a locomotive. Right after him a stray dog crams in and lies shaking on Czarnecki's bent back. A shell explodes very near. The dog is torn in half - the head and the front paws remain intact, but the rest of its body is a bloody mash.

Earlier, on 3 October 1939, he was invited to a secret meeting with the founders of the Service for Poland's Victory (later renamed the Association of Armed Resistance by Gen. Sikorski) held in the basements of the seat of the Polish Saving Bank. The meeting was attended by: Gen. Kazimierz Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski, Col. Stefan Rowecki (a.k.a. "Grot"), Mieczyslaw Niedzialkowski, MP, Maciej Rataj, the Speaker of the Sejm, Prof. Roman Rybarski and Stefan Starzynski, the Mayor of Warsaw. The main item on the agenda was the creation of structures of the new organization. My grandfather was appointed the treasurer of the organisation. Thus started my grandfather's service as the head of Department VII of the Supreme Command of the Home Army, i.e., the manager of the Home Army's finances. He was best known under a nom de guerre "Leszcz", but he also used other pseudonyms: "Malcz", "Janusz", "Nawrot".

He organized the network of flats and houses which served as contact points, and developed the plan of operation "Goral"* carried out in 1943 [*"the highlander" the operation took its name after the 500 polish zloty notes issued under the General Government, which had on their obverse a portrait of a man wearing a traditional dress of Polish highlanders - translator's note]. As a part of the operation the soldiers of the Resistance Movement took over several German transports of cash. The cash was later used for buying foreign currencies and gold all over the General Government territory. Then, those hundreds of thousands of dollars were put on the market very often causing the fluctuation of the exchange rate.

In 1964 the London Chapter of the Former Home Army Soldiers issued a certificate confirming that on 2 October 1944 my grandfather had been posthumously awarded with the Gold Cross of the Order Virtuti Militari by the Commander of the Home Army.

Jerzy Thun,

In 1943 "Baszta" battalion was transformed into a regiment consisting of three battalions: "Baltyk", "Olza", "Karpaty". At first, "Baszta", together with "Radoslaw" Group were to be the security units for the Headquarters of the Supreme Command of the Home Army located in Mokotow borough. Shortly before the outbreak of the Uprising the Supreme Command's headquarters had been moved to Wola brough. As a result the mobilisation point of "Radoslaw" Group was moved to Wola as well. However, by the order of the Commander of Warsaw Military District, Col. "Monter", "Baszta" regiment remained stationed in Mokotow.

Only after the Polish October of 1956 was he allowed to practise his profession. Eventually, he ended up working as a master for the Polish Ocean Lines. He spoke Hungarian, which he had learnt during his stay in that country. In 1946, in Gdansk, he met his future wife, Wanda Pienkowska, who had fought in the Warsaw Uprising as a combat medic.

My father died on board ship in Karachi, Pakistan on 12 October 1982. He is buried in Witomin Cemetery in Gdynia.

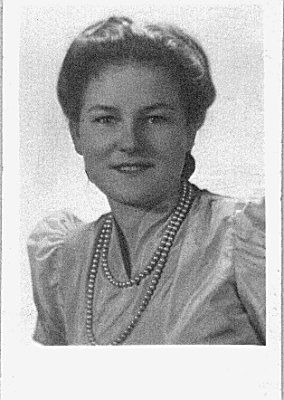

Wanda Thun nee Pienkowski,

Wanda Thun nee Pienkowski

Wanda Thun née Pieńkowski elaboration: Maciej Janaszek-Seydlitz Copyright © 2010 Maciej Janaszek-Seydlitz. All rights reserved.

The 10th Anniversary of Polish Independance Medal

On New Year's Eve 1931, at the First Assembly of Former Political Prisoners Stanislaw was awarded the Commemorative Badge of Political Prisoners 1914-1921 for the time he had spent in Russia as a prisoner of war.

Soon after that he was also granted the right to wear the Commemorative Badge of the 2nd Regiment of the Polish Legions. The privilege was granted by the order of the Regiment's commander, Col. De Laveaux (no Christian name again).

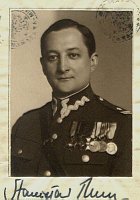

Stanislaw Thun in his officer's uniform

Document of Identification 1936 r.

Stanislaw's commitment to literature and publishing must have been strong indeed, and he must have made substantial contributions to the field since the Polish Academy of Literature presented him with the Academy's merit award - the Silver Academic Laurel. The award was presented on 5 November 1935 by the Secretary of the Academy Juliusz Kaden-Bandrowski and the President of the Academy Waclaw Sieroszewski. The Academy, a cultural institution, had a very limited budget so the awardee had to pay 18 zlotys to cover the cost of the medal and the award certificate. For that purpose, a blank payment form was attached to the letter informing about the award.

From 1924 to 1925 and from 1930 to 1931 Stanislaw was a member of the Association for Military Knowledge. From 1935 to 1937 he was a deputy member of the management board of the Association. He was an editor of the Military Publishing Review (published since 1926 as a supplement to Bellona). He was also an editor in the Infantry Review and the Military Review (from 1929 to 1933).

In 1936 my grandfather may have travelled to Palestine. A temporary passport valid for one trip issued in April by the Starost's Office would indicate so. It contains a Romanian transit visa as well as a one-month valid business visa issued by the British Passport Control Office.The declared purpose of the trip was a visit at an international fair in Tel Aviv. However, the passport does not contain any boarder stamps.

In 1937/38 he made a trip to Constanza. Little is known about the purpose of the trip, but most probably, as in the case of the trip to Palestine, it was an intelligence assignment.

On 30 July 1938 in recognition of his various pro bono activities my grandfather was awarded the Gold Cross of Merit by the Prime Minister Slawoj-Skladkowski.

The Gold Cross of Merit award certificate

A robust scout, my grandfather took up a demanding sport - sailing. He took his first steps as a sailor back in 1919 in Cracow, where he was mentored by Gen. Roja. In 1920 he became a proxy for the Polish Association for Sea and Inland Waterway Transport Co. "Baltic" with the right to sign cheques and the official documents of the association. In the following years he was mastering his helmsmanship on the Baltic Sea under the instruction of Mariusz Zaruski [a pioneer of Polish yachting - translator's note]. He spent several holidays at sea making voyages to Bornholm and Visby in 1931 and 1932 accumulating sea mileage required for obtaining a yachtmaster's license (the highest qualification for yachtsmen). He was awarded the license in 1932. He made some of his trips to Gdynia together with his son.

The Defence of Warsaw

During the September Campaign of 1939 my grandfather was a commander of the 2nd Volunteer Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment (later 336th Infantry Regiment) defending Praga [a borough in Warsaw - translator's note], in which he served throughout the whole defense of the capital.

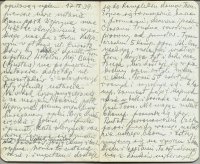

Some of my grandfather's documents from that period survived, e.g., maps, his private diary, general orders and a map holder (the map holder bears a sign in Hungarian so the grandfather must have had it since the Carpathian Campaign). The identification document issued by the Warsaw Defense Command has neither a number nor the date of issue, but it has the stamp and the signature of the regiment's commander, Col. Sosabowski. According to the ID Stanislaw was assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment. From 7 September 1939 my grandfather was at the disposal of the commander of Warsaw Citadel.

A sketchy plan of Praga shows the defence positions held by the grandfather's regiment. The positions were prepared to defend the city against the Germans who, according to information in the general order of Col. Sosabowski from 15 September, were approaching the eastern boundaries of Grochow [a borough of Warsaw adjacent to Praga - translator's note]. The order contained detailed instructions on the methods of fighting, the types of weapon to be used, the methods of transporting supplies necessary for the defence (e.g. sand bags). It also contained numeric security codes for each day. On 17 September my grandfather's battalion "Gustaw" charged the enemy positions and came under heavy fire. The entries in my grandfather's diary captured the atmosphere of the first days of the war much better than dry reports and orders:

On 1 September morning the people queueing for flour in the Anti-Aircraft and Antigas Defence League in Piernackiego Str. had not yet heard about the outbreak of war. The air ride sirens and real shooting were mistaken for another drill. Only after having heard the news on the radio did we realize our mistake. I had never expected the war to break out. Waiting for my mobilization orders - the draft commission announced that there would be no assignments for volunteers - I hear now and then about friends who have already received their active duty assignments, and I am sorry that I still have to wait. I'm managing the secretariat of the Polish Association of Book Publishers. The air rides have started. There were some air skirmishes on the first day, e.g., over the Unii Lubelskiej square. People's reactions are varied: some people are terrified, some do not care, some pray and some are full of bravado.

Then on 5 September, in the middle of the night, watchmen in Laski wake me up suddenly saying that the Germans have broken through our defence lines near Plonsk, and are heading for Warsaw. Along the road lit by moonlight walk the nuns from the Institute* carrying spades and singing a litany. [*the institute of blind people - a renown educational institution for blind children run in Laski since 1911 by the Association of the Blind People - translator's note]. They are heading towards Wawrzyszew to dig anti-tank trenches. Jurek and I burry provisions, arms and uniforms. We leave in a britzka together with the headmaster of the local school, 2nd Lt. Sokolowski.

It is still dark when we reach the city military command. Once there, we receive an assignment to Warsaw Citadel. Having reported in the Citadel I am put in charge of the battalion of Lt.Col. Sikorski's (a teacher in a municipal school in Poznan). The battalion is 150 men strong. I choose my officers and NCO's from those who have gathered in the Citadel. Janek Wilczynski - some friends are already here. The whole place is very crowded and extremely dirty.

We are together, the young and the old who have not expected to be called to arms ever again. People of all walks of life are animated by the same desire - we want to fight. At last, on 9 September my battalion leaves the citadel to take its positions between the railway bridge in Zoliborz [a borough in Warsaw - translator's note] and Gdansk Railway Station. It is the third line of defence but it is better than nothing. We are quartered in a school opposite the railway passage through to Zoliborz. The refugees from Lodz tell us what they have experienced - bombings, tanks. Our patrols are picking out soldiers from scattered units and include them in the ranks of our battalion. Unfortunately, the 2nd Company, together with Lt. Bielawski and Lt. Komar-Gacki, has been repositioned to Palmiry never to return. It has been attached to the batalion of the guards.

An excerpt from the diary, September 1939

24 September. There is no sign of German activity between the lines. Our ambush patrol came back with nothing. Warsaw is still being bombed. The Royal Castle is burnt down, and now the Grand Theatre has allegedly been destroyed, too. The city centre is slowly turing into a heap rubble. It breaks my heart listening about it. Our beloved Warsaw is dying. I cannot imagine it being the capital after the war. The reconstruction will have to take a long time.

25 September. We hear all sorts of rumors about our political situation. The newspapers are not coming out so people rely mostly on hearsay. In the last few days there has been talk that Gen. Sosnkowski committed suicide, that the British air force was fighting the Germans over Warsaw, that the Soviets declared war on Germany. The last one turned out to be true. A couple of days ago we learnt that the Soviet Army had crossed the Polish boarder allegedly with no hostile intentions. As of today, they are said to have come near Lwow and Brzesc. The Soviet embassy is in Warsaw. What is the meaning of all this? Our divisions near Lwow are said to have been disarmed and interned, and there was some heavy fighting in the streets of Grodno. Our situation looks hopeless, but we have been through worse, and in the end we have always come up victorious.

29 September. We are paying out the soldiers. The officers have received their pays too. The arms we are to surrender have been damaged. The soldiers have broken the firing pins and crooked the muzzles. The cannons have been dismantled, the locks thrown away.

Those were the last words my grandfather put in his diary he kept during the defence of Warsaw.

On 29 September, facing defeat, the commander of the Grochow sector, Col. Sosabowski, issued the general order No.28, in which he addressed his soldiers as "the defenders of Warsaw" and praised their "courage and fighting spirit". At the end he said: "keep up your spirit; wait for the order".

On the same day, the commander of the group, Col. Zongollowicz, issued an annex to his general order announcing that the Commander of the Army "Warsaw" had instructed him to award the Cross of Valor to Maj. Stanislaw Thun, Capt. Antoni Chrapczynski, 2nd. Lt. Alfred Haak, Ens. Stefan Szuba.

The Underground Resistance

After the surrender the gandfather had to report to the German Command Warshau, which he did on 31 October 1939. He was issued a Bescheinigung (certificate) No. 6658.

Grandfather's photo, end of 1939 r.

At that time the grandfather lived in a flat in Kanonii Street, on the edge of the Vistula Valley, which he called his little Venice.

When the uprising broke out the members of the Surpeme Command ware to remain at their battle stations and not to reveal themselves. For a frontline soldier my grandfather was, the inactivity was a torture. On 3 August he was waiting for orders in a flat at 24 Leszno Street, when, in order to ease the tension, his colleague suggested that they could go to the roof and fire at the German positions at Pawiak [the infamous German prison for Polish political prisoners - translator's note]. When my grandfather was approaching the window he was shot and killed by a German sniper. His body was wrapped in cloth and buried in the yard by Col. "Pirat" and Capt. "Alan" (Antoni Baranowski). On the following day, his body was dug out, placed in a provisional wooden coffin and reburried.

After the war he was exhumed and interred in Powazki Military Cementery.

photo of the grave in Powazki Military Cemetery

Virtuti Militari 4th class (the Gold Cross) award certificate

born 15.06.1924 in Warsaw

soldier of the Home Army, corporal - cadet, nom de guerre "Kot"

1st Platoon, 3rd Company, 'Olza' Battalion, "Baszta" Regiment, Home Army

My father became a soldier of the Resistance Movement at the age of 17. He was assigned to the elite Home Army Supreme Command's Security Battalion "Baszta", in which he went through an extensive military training. He also completed an officer training course in an underground officer school attaining the rank of corporal-cadet.

The units constituting "Baszta" battalion had orders to capture on the outbreak of the Uprising several strategically important buildings kept by the German forces. Except for the "Baszta" there were several other underground army units stationed in Mokotow.

On 27 July 1944 Col. Monter put all Warsaw forces on highest alert, but on the following day the alert was called off. It caused certain confusion as some of the soldiers who had reached the assembly points of their units remained there and some went back home.

When in the morning of 1 August all units were ordered to go into action at 05:00 p.m., due to the problems with communication, not all units managed to assemble their men in time. Additionally, not all of the insurgents' limited supply of arms and ammunition was put into use.

The fights in Mokotow started in a somewhat chaotic way. Facing strong resistance of the German forces supported by machine guns, artillery and tanks, the poorly manned and armend insurgent units were unable to accomplish the planned objectives, and sustained heavy losses.

In the areas under their control, the Nazis started the mass executions of the wounded and captured insurgents as well as civilians. One by one, buildings were set on fire.

Jerzy "Kot" Thun's unit was decimated and scattered already on the first day of the Uprising. My father found a hideout in a house, whose residents offered him help. On 5 August the Germans drove out all civilians from the area. My father, who had a very childish face, had his had covered with a kerchief, so that he could pass for a girl, and left the city as a civilian. Luckily, the group of civilians in which my father was avoided execution. Having left Warsaw my father came across a group of Hungarian soldiers going back to their home country. They took my father with them, thus he avoided being shot or sent to a death camp (those were the only two alternatives the captured insurgents had at the beginning of the Uprising).

After several months spent in Hungary, in the spring of 1945, my father came to Cracow, where he learnt about his father's death. When he reached Warsaw the grandfather's body had already been exhumed. Jerzy learnt about his father's resting place in Powazki Cemetery from Mrs. Sawicka, my grandfather's former colleague. Jerzy did not know what had become of his mother so he was on his own. The little help he had came from his aunt who lived in Silesia, and from his father's old friend - Dr Stobiecki from Cracow. In those circumstances he decided to find a school that would not only teach him a profession but also provide him with food and accommodation. Thus he applied to the Maritime Academy in Gdynia. It was also a continuation of his fascination with the sea he took after his father. After the graduation he had his seaman's book revoked because of his former service in the Home Army. He took to working part-time in Gdansk Harbour, and then on tug boats.

born 21.11.1924 in Mrowna estate near Leczyca

soldier of the Home Army, combat medic nom de guerre "Wandzia"

1st "Jozef Bem" Squadron of Horse Artillery, medical unit

From November 1942 she was a member of the Home Army Women's Auxiliary Service. She completed a course in battlefield first aid and an infantry weapons proficiency training. She also worked as an intern in the Holy Infant Jesus Hospital and Ujazdowski Hospital. She took part in the action of gathering medical supplies. During the Uprising she fought in Mokotow.

My Uprising

For me the Uprising started on 28 July 1944 when I was mobilized. I was assigned to the first aid post in Chelmska Street. Together with a few colleagues I spent the whole night in a barn on the bank of the Vistula River. We watched the flares being sent up over the river. On July 30 we were orderd to return home. The next mobilization order came on 1 August around noon. My mother wanted to stay with me as long as possibile so we both took a carriage to Chelmska Street.

Two hours before the W-hour our first aid post was relocated. We moved all our ecquipment to Stepinska Street not knowing that German troops are stationed opposite our post, near Lazienki Park. At 05:00 p.m. the shooting began. We saw a boy falling in the street so we run out with dash carrying a stretcher and wearing armbands. We were caught in the rain of bullets that fell on us together with leaves. The boy on the stretcher was killed and the four of us took cover under the roof over the entrance to a bomb shelter, many of which had been built by the Germans in the city squares. Having seen what had happened, Wanda - the fifth member of our group - run to us carrying bandages but she was immediately shot in both hands. Some boy also took cover in our shelter. Then, suddenly, we heard the Germans. They threw a grenade, which fell on Stasia Stawska's belly. The boy grabbed it and threw back immediately. A moment later another one - an egg grenade - was thrown in. The boy threw it back again. We could hear the Germans talk. At that moment the boy run out of the shelter. I do not know if he managed to escape. One of my friends - Tenia Zdziarska - went outside waving a white handkerchief. Unfortunately, she was shot, and the bullet went through a clavicle. The Germans came. Tenia could not move. We pretended to be civilians (we had thrown our armbands into the stormdrain in the shelter's floor). One of the Germans said they would take her to hospital and ordered the rest of us to go towards Lazienki Park. Once there, we were lined up against a wall, and one of the Germans started aiming his rifle at us. We were terrified! My whole life flashed before my eyes, and I knew that those were the last seconds of my life. Then another German came running and shouting "halt! halt!". The soldier aiming at us lowered his rifle. We narrowly escaped being executed. We were orderd to go into the building opposite Lazienki Park. We spent the night together with its residents in the basement. We demanded that the Germans take Wanda "Czarna" (Black) (I do not remember her real name), who had been shot in the hands, to hospital. German nurses were to take care of Tenia, who had been shot in a clavicle. Indeed, on the following day a lorry came and took Tania, who was lying on a stretcher, and Wanda to hospital. They both survived the war. There were three of us left: Stasia Stawska, Wanda Choryd "Biala" (White) and I. (After the war Wanda Choryd became a professor of psychiatry). Three girls in our unit were named Wanda so we had to use nicknames: Biala (White) - for the one with blond hair, Czarna (Black) - for the one with dark hair (Wanda Szeruda) and Wandzia (a diminutive form of the name Wanda) - for me, Wanda Pienkowska.

Wanda "Biala" overheard a conversation between the German soldiers. They had just been withdrawn from the frontline and did not know what exactly was going on in Warsaw. We approached an officer and told him that we wanted to go home but a soldier lying on the roof shot at anyone trying to cross the square. We told the officer: "Tell him not to shoot at us." And so he did. Wanda and I parted with Stasia, who went another way. We run until we reached Chelmska Street. Then we came to an incline which we had to climb to get to Mokotow. The slope was covered with potato plants. We crawled upwards among the plants, with bullets whizzing over our heads. Finally, we reached Pulawska Street near the place where it crosses Woronicza Street. We moved on relying only on our instincts because we did not know who was in control in this part of Mokotow. In order to cross Pulawska Street we had to wait until dusk because the street was under constant enemy fire. We waited in an abandoned flat and ran across after it had got dark. We headed for the sector command in Szustra Street (today Dabrowskiego Street). When we got there our real babtism of fire started as the Germans began to bomb the area. The house which served as the command's headquarters was swaying, plaster was falling off the walls and the ceiling, window panes were shattered, gaping holes like windows were opening suddenly in the walls. We were surrounded by the roar of explosions and growing piles of rubble. It was difficult to find a place to hide because any place might have been hit by a bomb and annihilated.

We received an assignment to "Baszta" battalion. Our first job there was peeling potatoes in the kitchen (it was organized in the school on the corner of Woronicza Street and Krasickiego Street). With the hospital run by the Convent of St. Elizabeth filling up with the wounded, additional provisional wards were set up in the surrounding houses. There were a lot of survivors from the scattered units. We were quartered at 20 Krasickiego Street and assigned as nurses to various first aid posts. I was separated from Wanda "Biala". I was assigned to the post at 18 Lenartowicza Street. We were brought meals from the kitchen in Woronicza Street. The woman who brought us food had a nickname "Mamcia" (Mommy) and she was responsible for organizing provisions (I have met her once in Gdynia after the war but I think she was just on a holiday trip).

During the day the boys broke into some German warehouse and found some clothes. We received green blouses, brown skirts and grey coats made of blankets, which were extremely heavy. I was very glad because I had left home wearing only a grey dress made of thin cloth and a thin pullover. The garments I got were to be my only clothes for the next several months. One of the nurses working in my post was Zofia Zdziarska, the sister of Tania, who had been wounded on the first day of the Uprising. During the day we tended our wounded, and in the evenings we walked to Pola Mokotowskie to get water from a well. The Germans were using tracer ammunition therefore we had to wait for a short break between rounds to run across Lenartowicza Street. Having crossed the street we were well covered. It was much more difficult to cross the street on the way back when we carried a bucket full of water. Sometimes we managed to return to the post with the bucket only half full, but we considered ourselves lucky anyway because having any water meant a lot.

Even in those circumstances life was not too bad until "lowing cows" - incendiary missiles nicknamed for the sound they made in the air - started flying. After 12 of them flew over our post, all nearby trees were completely leafless, houses swayed and even the cobblestone in the street cought fire. We moved our wounded to the boiler room of the house at 126 Pulawska Street, but before long the German airforce commenced another air strike bombing all larger buildings. I was about to finish dressing the wounds of "Bialynia", who was a courier and was wounded in a hand and in the stomach at the racecourse in Sluzewiec [the course was a heavily defended German position during the Uprising - translator's note]. Then I heard a loud crash: something was crumbling and the air filled with dust. I jump out on the staircase to check if we would be able to get out. The stairs were covered with rubble but there was a way out. The building standing next to ours turned into a pile of debris. Having calmed down our wounded I run to my cousins'. The Grendyszynscy lived nearby in Krasickiego Street. I wanted to clean off the red brick dust that I was covered with, and which made me look like a wraith. My uncle Kazimierz, despite aunt's protests, decided to go back with me and help dig out the people buried in the basement of the collapsed house. I remember my aunt crying after him: "Kazik, don't leave me alone". We were running along the yards at the back of Pulawska Street when the bombers came back. My uncle shouted something. He probably wanted me to lie down along the fence, which was what he must have done. I saw some boys jump into a ditch and I jumped after them. It turned out that the ditch was partly covered. A moment later some dirt fell on our backs and the sunlight poured into our hiding place. When we climbed out we could not recognize the yards. Just next to our ditch there was a huge bomb crater, and on a heap of dirt ejected by the explosion lay my dead uncle. I did not have enough courage to go and tell my aunt about it. Besides, we were moving with our wounded to Lenartowicza Street. She learnt from the soldiers who were picking up the wounded and the dead. In the evening the aunt asked me to come. The uncle lay on a provisional bier in the living room in a pool of blood. His scapula was torn off and he had a hole in the head. He was buried in Dreszer Park. A week later their only son called Zuk was killed too. He was also buried in Dreszer Park.

One of my wounded had been shot in rather peculiar circumstances. The boys had cought a horse somewhere. One of them had been cleaning the horse while another one had been cleaning his shotgun. When the latter had accidentally hit the horse with the stock the shotgun had gone off and he had been hit in a thigh. His thigh was full of lead shot, which could not be removed in the primitive conditions we had to deal with. So the not-very-valiant soldier could not walk and had to lie in our post.

We were stationed in Lenartowicza Street until the end of our fights in the Uprising. On 18 September we saw American B-29 "superfortess" bombers dropping supplies. They flew in a formation as if it was a parade. We looked in the sky full of hope, and the view was magnificent. They flew very high over ground to avoid the fire of the German air defence. Unfortunately, most of the supplies fell into German hands.

On 24 September the Germans launched a full-scale attack on Mokotow. They used all available weapon against us. Everyone who was at least able to limp on his own grabbed a stick or a board to use it as a crutch, and, hiding in trenches and ditches, tried to escape toward the city centre. Three boys who could not walk and "Bialynia" were left. Zosia and I volunteered to stay with them. All civilians had left their homes running from the Germans. We carried the wounded to the basement. Then suddenly the cannonade stopped, and SS units entered the area. We pretended to be civilians. At first, the Germans ordered us to carry the wounded outside so that they could be transported to a hospital near Warsaw. Each of us took one of the wounded on her back and we dragged them up the stairs to the yard. We did not have enough strength to carry them any further. The Germans watched the whole scene smirking. Suddenly, they told us to carry the wounded back downstairs and go to a house in Krasickiego Street where they had found two wounded who, for some reason, had been left alone. It turned out that those two had guns hidden under their pillows so the Germans knew that they were not civilians. We carried them to our post and put them next to our wounded. All the time the Germans were telling us that they were going to take the injured to a hospital. One of the Germans told us to stay with the wounded, but then, another one who seemed to be from Silesia said in Polish "You go home". So we went out to the yard. The windows of the basement where we left our wounded were looking on the yard.

When we were crossing the yard we heard gunshots, and we realized that the Germans killed the wounded boys who lay helpless in their beds. We froze in terror when we realized that at any moment we could share their fate. One of the SS soldiers, a Ukrainian, approached us and demaded a watch. Zosia, who was scared to death, took off her watch and gave it to the soldier without saying a word. Then we went away unmolested. I can only remember the names of two of our wounded: Kazik Kozieradzki and ...Wodkowski.

We followed a group of people going towards the racecourse in Sluzewiec. On the way we met one of the residents of the house in which we had had our first aid post. He rode a rikshaw carrying "Bialynia" in the passanger's seat. He must have taken her out of the basement during the commotion as we had been carrying the wounded. Now he was helping her to get out of that hell. We reached a stable where we spent the night. In the morning lorries came and took all the elderly, wounded and mothers with children to Pruszkow [a town at the outskirts of Warsaw, in which the Germans set up a refugee camp for the people forced out of Warsaw during and after the Uprising - translator's note]. The rest of us had to walk.

We were leaving the ruined Warsaw. When we were walking by the airport Soviet planes appeared in the sky and our German escort went hiding. Some women coming back from work in the field were walking along the shoulder of the road so Zosia and I joined them quickly. In this way we escaped from the transport to the camp in Pruszkow. When we reached Grojecka Street we saw a German checkpoint. We had no ID's! We saw some children pulling carts loaded with potatoes (It was Rakowiec, we were already outside Warsaw so the life there was going on as usual in comparison to what was going on in the city). We joined them and avoided the documents check. We ran across the field towards Otrebusy, where a station of the Electric Suburban Railay was. When we came at the station we were dumbfounded: there were fruit and vegetables stands. We were in a different world. It was hard to believe that the life there was so normal. I parted with Zosia at the station. She went to her friends in Grodzisk and I decided to go to the Wehrs, who had been our neighbours before the war, and had an estate next to ours. Twenty people had been already staying in the Wehrs' house when I got there. My aunt Jadzia Jokiel was among them. All the youth slept in straw together covered with blankets in a small shed. Aunt Jadzia slept with us as a chaperone.

The people were transported out of Warsaw by trains. Therefore every day we went to the station and when the trains stopped or slowed down we handed out bread and water. The Germans tried to scare us off but we managed to help the exhausted passangers. When a German went to one end of the platform we immediately showed up on the other.

Mr Wehr helped me get a new ID.

From time to time Janek Jonkiel showed up in Grodzisk. His paid a short visit and disappeared again. As a member of the "Dark and Silent" [an elite formation of special operations officers dropped over the German-occupied territories to gather intelligence and engage in sabbotage operations - translator's note] he had to remain under cover. He revealed himself only to the closest family.

At the beginning of October we heard news that the sick and wounded from Wola Hospital were to be transported to Milanowek, and that my mother's sister, aunt Marianna, was among the wounded. She had been admitted to hospital after she had been seriously injured in the explosion of a grenade thrown by a soldier of Vlasov Army. So we took the aunt to Grodzisk, but we could not stay there for too long because, despite the Wehrs hospitality, the house was too overcrowded to allow for any more guests. It was also more and more difficult to get provisions.

nom de guerre "Wandzia"

Home Army soldier, combat medic

"Jeremi" Company

1st "Jozef Bem" Squadron of Horse Artillery, medical unit

transaltion: Paweł Wójcik