Fr. Col. Tadeusz Joachimowski a.k.a. "Budwicz"

The priestly service in the Warsaw Uprising

On September 1, 1939 the forces of the Hitler's Germany crossed the borders of the Polish Republic, without declaring a war. On September 17 a new aggressor, the Soviet Russia, joined them. In spite of the heroic defense, the Polish Army did not equal prevailing forces of the enemy. After few weeks of fight Poland was occupied by the outside armies.

Unwilling to set their names to the country's capitulation, the Polish government crossed the Polish border with Romania in order to continue their activity in exile. Some soldiers and officers were taken prisoner, while another part, alike civil authorities, left the country to continue armed resistance.

As soon as in the autumn 1939 the origin of the Polish Underground State was created. Polish officers who stayed in the Homeland, having not been taken prisoner, started to form underground armed forces which were an armed part of the Underground Poland. Like always in the history of the Polish sword, the military ministry entered upon the service, too.

The Polish Army field bishop Fr. Jozef Gawlina, on leaving Warsaw, appointed Fr. Maj. Stefan Kowalczyk, a chaplain of 36 infantry regiment of the Academic League, to a post of a vicar-general, on September 8, 1939. Thanks to that, consecutiveness of the church authorities in the army on the area of Poland was preserved.

In the middle of the year 1941 the Home Army Chief Commander Gen. Stefan Rowecki a.k.a. "Grot", appointed Fr. Col. Tadeusz Joachimowski a.k.a. "Budwicz" to a post of the Home Army Chief Chaplain. This decision was confirmed by the field bishop Fr. Jozef Gawlina, who had given him a duty of the Chief Chaplain of the Armed Forces in the State.

Fr. Col. Tadeusz Joachimowski a.k.a. "Budwicz"

The appointment was accepted by the Commander-in-chief Gen. Wladyslaw Sikorski in the year 1943. This is how a situation in the underground ministry looked like. What followed was development and unification of the priestly service in the underground army. A Polish territory between the borders before September 1, 1939, was divided into six parts, each of whose having had a dean. These parts were partitioned into districts meaning provinces and led by district deans, and districts were divided into smaller districts, regions and outposts respectively.

Fr. Col. T. Joachimowski took over a secret name "Nakasz" (Naczelny Kapelan Sil Zbrojnych). He established a seat of the Field Curia in St. Roch hospital in the Krakowskie Przedmiescie in Warsaw. Curial files were bricked up in a building in the Koszykowa Street Number 78 (not far away from a contemporary MON, i.e. the Ministry of National Defense, hospital), where were buried during the Uprising. The Home Army Secret Field Curia (also known as the Leadership of Ministration Service) was led by:

- the Polish Army vicar-general Fr. Col. Tadeusz Joachimowski a.k.a. "Budwicz",

- I substitute Fr. Prelate Col. Jerzy Sienkiewicz a.k.a. "Guzenda" or "Juraha",

- II substitute Fr. Maj. Stanislaw Malek a.k.a. "Pilica", a pre-war dean of DOK 1 (Dowodztwo Okregu Korpusu 1 - Army Corps' District Command) and KOP (Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza - the Border Guard), an ex-chaplain and a parish priest of the garrison church in Rembertow,

- curial chancellor Fr. Zbigniew Kaminski a.k.a. "Ksiadz Antoni", a rector of the St. Anne academic church, openly performing duties of a hospital chaplain.

The whole Home Army Ministration Service was under authority of Fr. "Budwicz." He commanded it with a helping hand of chosen deans of the Home Army regions. A dean of the Warsaw Region Headquarters was Fr. "Pilica". After disclosing and separating the Warsaw District from the Warsaw Region and subordinating it directly the Home Army Headquarters, Fr. Maj. /Lieut.-Col. Stefan Kowalczyk a.k.a. "Biblia" or "Vikagen" became a Warsaw District dean.

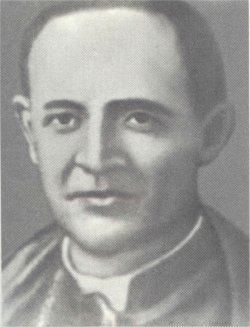

seals of the Home Army Warsaw District Headquarters' Ministry Leadership

Due to vastness and a great number of the Home Army units, the Warsaw District was divided into four sub-districts (vice-deaneries) having rights of divisional ministries:

- Southern Warsaw (Warszawa Poludnie) in the southern direction from Aleje Jerozolimskie - vice-dean Fr. Stanislaw Piotrowski a.k.a. "Jan I ", substitute of Fr. "Biblia",

- Northern Warsaw (Warszawa Polnoc) in the northern direction from Aleje Jerozolimskie - vice-dean Fr. chaplain Jan Salamucha "Jan"; from the St. Jacob church in the Narutowicza square, assistant professor from the Jagellonian University's Theology Department;

- Prague Warsaw (Warszawa Praga) - vice-dean Fr. Jan Kitlinski "Szczepan";

- Warsaw administrative district (Warszawa powiat) - vice-dean Fr. Leon Pawlina, manager of the Catholic House "Roma" in the Nowogrodzka street.

To vice-deans, chaplains of districts, whose structure corresponded with duties of units' chaplains, were subordinated the following:

- District I Srodmiescie - dean Fr. chaplain Jan Wojciechowski a.k.a. "Korab";

- District II Zoliborz - dean Fr. chaplain Zygmunt Truszynski a.k.a. "Alkazar";

- District III Wola - dean a.k.a. "Strus";

- District IV Ochota - dean Fr. chaplain Jan Salamucha a.k.a. "Jan";

- District V Mokotow - dean Fr. chaplain Mieczyslaw Mielecki a.k.a. "Mietek";

- District VI Praga - dean Fr. chaplain Jan Kitlinski a.k.a. "Szczepan";

- District VII Warszawa Powiat - dean Fr. chaplain Leon Pawlina and Fr. chaplain Mieczyslaw Paszkiewicz a.k.a. "Ignacy".

Districts were divided into regions, where posts of a region chaplain and so-called sanitary chaplains (for ministration work in future sanitary hospitals) were situated.

In particular regions of District VII ("Obroza") there were the following deans:

- region 1 Legionowo - Fr. chaplain Waclaw Szelenbaum a.k.a. "Bonus",

- region 2 Marki - Fr. chaplain Andrzej Ploszan and Fr. chaplain Antoni Wisz,

- region 3 Rembertow - Fr. chaplain Stanislaw Skrzeszewski,

- region 4 Otwock - Fr. chaplain Jan Raczkowski,

- region 5 Piaseczno - Fr. chaplain Jan Zajac a.k.a. "Robak",

- region 6 Pruszkow - Fr. chaplain Waclaw Herr,

- region 7 Ozarow - Fr. chaplain Alfons Pellowski and Fr. chaplain Madej,

- region 8 Lomianki - Fr. chaplain Jerzy Baszkiewicz a.k.a. "Radwan".

Such structure of the underground military ministration service lasted until the Uprising. Fr. "Budwicz" organized secret briefings of dean fathers and district chaplains in a building in the Mirowski square number 18, in the Dluga street at the Pallotine friars', as well as in his own house in the Hoza street.

Now all the "Obroza" regions took part in the Uprising so the ministration service was not everywhere mobilized to open fighting. In those regions that participated in fight, its forms were different. Consequently, chaplains' role was different, too. A place of the most intensive action in the region VII "Obroza" was region 8 Lomianki - the Kampinos forest.

Fathers-chaplains worked in the underground both in city clandestine units, in diversionary groups and in forest guerrillas' units. What emerged was a need to provide numerous chaplains with essential liturgy accessories such as field chasubles, albs, stoles, missals, etc. Fr. Capt. Waclaw Karlowicz a.k.a. "Andrzej Bobola" organized, with help of people working in the Warsaw Fibre Factory in the Bema street, several bales of appropriate black and white cloth, from which nuns soon sewed about one hundred chasubles, surplices, albs, burses, stoles, etc. They all were stored in a capitulary of the St. John archsee in the Old Town.

Workers of a private printing-house in the Skierniewicka street made, secretly and free of charge, more than a hundred missals of a military format that were needed by fathers-chaplains in the field. Fr. "Andrzej" was fortunate to make little crucifixes for field altars produced in another workshop. For this work Fr. "Andrzej" was rewarded the Silver Cross of Merit with Swords.

The Polish Army vicar-general Fr. Col. "Budwicz" wrote a prayer-book for the Home Army soldiers, entitled In the service of Christ and Homeland (W sluzbie Chrystusa i Ojczyzny), which included A Prayer before a battle (Modlitwa przed bitwa):

"To You I'm resorting, my God, at this, maybe the last, moment of my earthly journey. I'm going to deliver battle in defense of the holy faith and my Homeland. I wish to fulfill my duty as good as I can.

Give me, oh God, strength that I need, fortitude and courage, for me to carry out my commands' orders and not to tarnish the honour of a Polish soldier.

If I were to fall on a battle-field, I believe that you will welcome me to your grace, as I have always wanted to be your soldier, as I'm fighting in defense of my family and the soil, love towards whose you inculcated in my mind.

And if you allow me to have a winning battle, I will not be looking for my praise. Not to me, but to your Name may glory be forever. Mother of God - protect the ranks of your soldiers.

My Guardian Angel, do not leave me.

Amen".

In a period between the wars, in comparison with other Polish cities, Warsaw was not too religious a city. Similarly as in other big European agglomerations, a great part of intelligentsia was interested in new intellectual currents and a lot of physical workers had leftist tendencies.

Such realms changed after the war outbreak. During the occupation, influenced by a shock caused by the state's fall and constant life threat, thousands of Varsovians came back to regular religious practices and would look for consolation and hope in prayer.

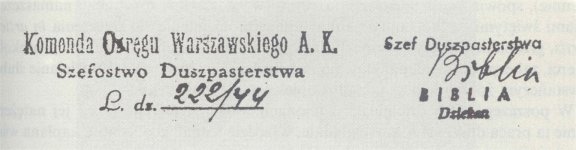

In first occupational years emerged a custom of raising both small chapels nearby houses and little home altars. This phenomenon became widespread especially in the spring 1943 and was a kind of reaction to an escalating wave of terror and tragic historic events (Katyn - the matter revealed on April 13, 1943 by German media, the Rising in the Warsaw Ghetto and the death of General Wladyslaw Sikorski on July 4, 1943).

The practice of raising little chapels attached to a homestead was known in all Warsaw districts during just few months. Little chapels and home altars were a typically Polish custom. They used to be built thanks to voluntary gifts that came from collections among the inmates of a particular tenement-house. The chapels' appearance depended on house's size, wealth and invention of inhabitants. There were both small, wooden or metal boxes hung on house walls, as well as little chapels put on special plinths or splendid free-standing structures situated in central, representative parts of courtyards. A ceremony of a new chapel's blessing would gather the whole house community.

a little chapel in a courtyard of a Warsaw tenement-house

They did play a significant role in Warsaw inhabitants' life during the occupation. Apart from a place of religious practice, after a curfew, they were a place by which the inmates of a tenement-house used to gather not only in order to pray together, but also to share the news, opinions or listen to the newest gossip. Besides religiousness of the society, caused by occupational life conditions, one would demonstrate by them not only one's faith in God but also one's patriotism. The chapels became a binder for each local community to which all social groups belonged. Simultaneously, they were conducive to strong interpersonal bonds being created.

On August 1, 1944, in the morning, the Home Army Field Curia received orders to participate in the Uprising. Fr. Maj. /Lieut.-Col. Stefan Kowalczyk "Biblia", the District Dean, started at 11 a.m. a briefing with a presence of fourteen subordinate vice-deans and district chaplains. The meeting took place in the Pallotine Friars' house in the Dluga street, which was a pre-war seat of the Field Curia. Commands and tasks were given, organizational settlements for the time of fight presented and a common prayer for the success of the Uprising uttered.

The first days of the Uprising were tragic for the Home Army Field Curia. The Home Army Chief Chaplain Fr. Col. Tadeusz Joachimowski a.k.a. "Budwicz" at the time of the Uprising outbreak stayed in a house in the Elektoralna street number 47. This house found itself on nobody's ground, between insurgents' posts and German positions. In this situation Fr. "Budwicz" had neither influence on submitted to him ministration service nor contact with both the Home Army Headquarters and the Home Army Warsaw District Headquarters. While waiting for the former's orders, despite information about approaching Germans, he did not withdraw further back the insurgents' terrains and on August 7, together with civilians, fell into the enemy's hands. Germans made him join a group of men driven into a railway loading platform in the Wola district. The group of Polish men was closed in the St. Wojciech church for the night. In the morning, where Germans were leading them to transports, one of guards, having noticed a priest in the group, dragged him out from a line of persons and shot him.

On August 8 his I substitute Fr. Prelate Col. Jerzy Sienkiewicz a.k.a. "Guzenda" was caught by Germans. He was staying then in his lodging in the Leszno street and was also devoid of contact with the command. Fortunately he did not cast in his lot with his superior. Together with civil inhabitants of Warsaw he was sent to a passing-camp in Pruszkow. After short incidents he was lucky to leave that place; afterwards he went to the Cracow region.

II substitute Fr. Maj. Stanislaw Malek a.k.a. "Pilica" during the Uprising stayed in the Praga district, so he had no possibility to lead the cure of souls.

As matters stood, after the Uprising outbreak, the Field Curia did not have the commands, as a matter of fact.

The most important among chaplains was Fr. Maj. /Lieut.-Col. Stefan Kowalczyk "Biblia", the Warsaw District's dean. He took it upon himself to recreate loosen organizational structures of ministration service, bringing to life the Military Ministry Department by the Home Army Warsaw District Headquarters. Acting as the Chief Chaplain of the Uprising Warsaw Fr. Col. "Biblia", in the middle of August, in his guide's Teresa Wilska custody, went through the sewers to the Old Town where he inspected chaplains living there.

Fr. Col. Stefan Kowalczyk "Biblia"

It was extremely difficult to reconstitute ministry service at the time of the Uprising outbreak because some priests had been isolated far away from mobilization points. Most chaplains from the city were not able to receive orders on time and appear at previously established posts at "W" hour. Scheduled organizational activities were replaced by improvisation.

The whole responsible ministry work must have been done by chaplains and parish priests. This work looked differently in particular districts and fighting regions, depending on its vastness, yet everywhere the presence of a priest among insurgents in the forefront of the fighting line was needed and looked forward to.

Apart from the district chaplains who have been mentioned, also insurgent units and battalions had their chaplains. Chosen chaplains would take care of insurgent hospitals, as well.

In the Kampinos Forest, where units of region 8 of VII District "Obroza" were fighting, Fr. Chaplain Jerzy Baszkiewicz "Radwan I" was a leader of ministry service, both at the conspiracy time and during the Uprising. He was given aid by, among the others, Fr. Stefan Wyszynski "Radwan III", the then chaplain of a field hospital of a "Kampinos" group in the Institute for the Blind in Laski, who later on became the "Primate of Millennium."

Work was a bit safer here, not in dread of everyday bombing, yet this huge area made priests walk for many kilometers with the blessed sacrament. Chaplains visited particular units, also those protruding fighting posts. Often they found themselves in the front line. The units marching out for big fighting actions were given by their chaplains general absolution in articulo mortis.

On Sundays and feast days on a parade-ground in Wiersze field masses used to be offered. They gathered members of the underground army and inhabitants, many of whom were confessed and received Holy Communion; brides and bridegrooms were wedded and children were baptized.

Chaplains who cured of souls in the fighting Warsaw had numerous duties. They would administer an oath to mobilized soldiers, bless units' banners, say masses for the Homeland in places of danger points' gatherings and on national holidays, give Holy medals of the Czestochowska Holy Virgin for their charges and bless them.

Their duties included offering holy masses (sometimes even three per day), confessing, giving the Holy Communion, extreme unction for seriously wounded and dying people, giving absolution in articulo mortis, burying the dead, filling in special death certificates, putting dead people's property at safety, as well as wedding insurgent soldiers and taking care of the wounded, etc.

Uprising ministers participated in work of the Home Army District Headquarters as far as communication, press distribution, sometimes organizational and tactical activities were concerned. Conditions of insurgents' fight and civilians' existence leading to traumatic experience claimed special service from chaplains whose role became more meaningful. In next fight stages, when insurgent units withdrew or were evacuated through the sewers, chaplains stayed with the wounded and civilians, sharing their fate.

Apart from the ministration service, priests helped in rescuing burying churches and relics, protecting church treasures, for example carrying a coffin with remains of St. Andrzej Bobola from the Jesuit friars' church to St. Jack church in the Freta street, or saving from a cathedral an antique fourteenth-century crucifix from Nurnberg.

The Home Army Warsaw District Commander and the Warsaw Uprising commander-in-chief General Antoni Chrusciel "Monter" issued a Ministration Instruction (an order number 14) on August 11 concerning unification of morning and evening prayers in units, offering Sundays masses for the army where conditions would allow this, hearing confessions and giving the Holy Communion, burying the dead (this was a duty of chaplains or units' commanders), filling in special death certificates (a duty of chaplains, commanders or hospital office's workers together with giving the data to a military parish or to a District Headquarters ministration chief), putting dead people's property at safety and giving them a District Headquarters ministration chief, keeping a record of tombs, sending reports, weekly ones in the future, from ministration actions in the field, in sanitary points and in field hospitals. In the next order (number 19) General Chrusciel regulated matters connected with blessing marriages of people who belonged to the Home Army. The order required, among the others, to get an agreement from a ministration service chief to dispense a sacrament of marriage.

Both life and fighting conditions in the city made some chaplains' duties impossible to fulfill. For instance, due to great communication difficulties, regular sending of reports and the dead's property to the ministration chief was possible only in the City Centre. Most chaplains would have to make decisions concerning the sacrament of marrying without any contact with Fr. Col. "Biblia". Death certificates could not often be written as that required information about a place and circumstances of a soldier's death, which could be confirmed by witnesses.

Since the first day of the Uprising military chaplains had been of religious service for civilians and wounded people whom they met in the street, they offered masses for Warsaw's inhabitants and heard confessions, they also organized both military and civil funerals. Parish priests and friars were eager to help a fighting soldier, they often accompanied insurgents in the front line, they worked in field units and hospitals, assisted during funerals, took care of personal things belonging to the killed in action; they also kept a record of tombs.

Many priests and friars de facto served as chaplains, although they had never been appointed to such posts. In such specific circumstances of the Uprising, where a front was everywhere, one could observe close co-operation between parish and military ministers, despite a fact that each of them had separate organizational structures as well as range of tasks differed. The co-operation was so good that in many places a distinct character of both ministries would wear away. In the City Centre, where work conditions were the most convenient, some chaplains used to lead chats for soldiers. The ministry service of military chaplains, common masses for inhabitants and insurgent units did strengthen a bond between the capital's population and the army.

A great increase in religiousness during the Uprising intensified among Varsovians a need of sacramental life, which gave the civil and military priesthood additional duties. Some priests used to say 2 or 3 masses daily and 3 or 4 masses on Sundays, often under the enemy's fire. Confessions were being heard the long hours.

a Holy Mass in the "Nowosci" Theatre's courtyard, the Mokotowska street number 73

Many churches had been destroyed or damaged and when Varsovians had realized that the enemy would bomb places of worship on purpose, masses started to be offered in houses' gates, in private homes by improvised altars and the Holy Virgin figures as well as in front of courtyard chapels.

A Mass offered in one of Zoliborz homes

The more buildings were destroyed, the more often religious services were organized in basements which used to be called catacomb ones. Chasubles, ornaments and liturgical equipment were borrowed from churches and when there was lack of them, kitchen utensils were used. Military chaplains received wine and communion hosts also from churches.

An important task of the ministration service during the Uprising was "comforting hearts", raising people's and insurgents' spirits. To achieve that, the priesthood would mostly use religious, national or military feasts, and historic anniversaries. Solemn ceremonies were organized on August 6, i.e. on the anniversary of the First Cadre Company's marching out. A sublime mass with a patriotic homily followed by an insurgent company's march past made a great impression on the Old Town inhabitants. On August 15, i.e. a Polish Soldier's Holiday and a religious Feast of the Assumption, with remembrance of an unforgettable "miracle by the Vistula river", solemn field masses were said, wherever the conditions allowed that, and both soldiers and civilians participated. On the anniversary of the war outbreak a tribute was paid to the killed during the Homeland's defense.

On September 22, on the occasion of reorganizing insurgent units into the Home Army Warsaw Corpus, Fr. Maj. /Lieut.-Col. Stefan Kowalczyk "Biblia" issued an "Appeal to the soldiers". He emphasized a worth of an oath, honour and soldiers' virtues, which could be put to the test by unclear future.

In accordance with permission given priests, who were in the front, by the Pope, each priest had a right to offer three masses per day. In many units chaplains would give soldiers before a fight general absolution and the Holy Communion.

Extremely difficult life conditions during the Warsaw Uprising made religiousness and a need of sacramental life deeper among both civilians and soldiers of the fighting Warsaw.

An important part of religious life of the capital's inhabitants, as well as soldiers during the Warsaw Uprising,were masses. In the first days of the Uprising priests in liberated districts would offer solemn thanksgiving masses. For the first time for several years, by organ sounds, the congregation could sing religious songs as well as patriotic ones, forbidden by the occupant. For thousands of the faithful a great moment was the very fact that a mass could be offered openly, according to the Polish tradition, while singing patriotic songs, in the liberated city, for the first time for five years.

During next days of fight chaplains were trying to say masses in churches in the morning and in the evening every day; the insurgent press and announcements put in the streets would inform about these masses' exact time. Such time was chosen when German firing was believed to be the smallest.

Due to the fact that lots of people were eager to participate in these holy masses, priests used to say them on weekdays and on Sundays also outside churches: in hospitals, in courtyards by small chapels, in squares, in buildings' gates, in basements or private homes. People would pray, very concentrated. Usually all the faithful would go to communion. The masses allowed people to part with dramatic reality and to take heart thanks to the faith in God and His protection.

As time went by and life conditions in those districts that still belonged to insurgents went from bad to worse, more and more masses were said in Warsaw churches' and tenement-houses' underground. It also happened that, having met a priest, people said their prayers or a Rosary mystery, in the street. Other faithful would then join those people and a large group was formed which could attract the enemy's notice; insurgent commands in particular districts appealed not to create such concentrations because of the threat of constant air raids. However, a need of prayer was often so strong that safety requirements were underestimated. That is why many people were killed or wounded while coming to a mass or during a mass.

All reports in unison lay emphasis on religious zeal of Varsovians in those tragic days, and their striving for priestly service. Many a time people would go to confession simply in the street, just asking some met priest for giving absolution.

a conversation with a priest by a barricade in the Dobra street

Danger of losing life, common for everyone, covered up differences in philosophy of life. Religious devotion was showed also by those who were previously known to have had a liberal attitude towards the faith beliefs. A catholic priest was eagerly welcomed by members of the Evangelical Church. When a priest appeared in an insurgent hospital, generally all the wounded went to confession and to communion.

A mass was the most often ended with a song Boze, cos Polske with its chorus "Our free Homeland give us back, oh Lord, we beg You" and an extra verse: "Your one word, eternal Lord of heaven, will be able to raise us from the ashes, and when we will deserve your judgement, turn us into ashes, but free ashes".

Soldiers found matters of faith "scabrous" or even foibles. Usually one would not talk about them publicly; only in small groups people sometimes discussed religion and Catholic ethics. But when a chaplain arrived at protruding insurgent posts, all soldiers usually used to go to confession and communion. Also, if conditions were friendly, whole units went to confession before leaving for an action.

Heavy fights, constant air raids and gun-fire resulted in funerals being an everyday component of the Uprising Warsaw's life. While ruin of the city was growing and casualties escalating, their character also changed. During the first days of the Uprising, when there had been not many casualties yet, and the military ministration service had not been property organized, soldiers of lots of units would bury their dead in the places where they had been killed or on an accidently chosen area, in the neighbourhood of a battle-field. They made use of local priests' service. A priest uttered a prayer, he usually noted a dead person's personal data and their burial place; if a funeral was on their parish area, he made an appropriate registration into parish archives.

Priests, who were embracing duties of military chaplains, were trying to introduce such rules that would make it easier to find soldiers' tombs of certain units after the Uprising. They buried the killed ones in the rear of a front, in unchangeable places, for instance on a chosen square, on a courtyard, nearby a hospital, etc.

a small cemetery in the Skorupki street

Coffins were used in the first weeks of the Uprising. Later, to save space, the dead were buried at the bottom or on top of a coffin and this bottom was covered with planks or door, etc. If people ran short of these, dead bodies were wrapped in capes or sheets; when the end of fighting was near, the deceased's face was covered with a piece of material. A closed bottle with the deceased's documents inside was put to a grave by a chaplain and, if the dead person did not have any documents, a piece of paper with data received by their friends was put instead.

In the City Centre copies of these documents with information of a burial place were sent to the Ministration Command-in-chief. Remembrances of the killed ones, compiled by chaplains found their place there, too. In the districts that were not able to communicate with the Command-in-chief chaplains were storing all data; the most of that records lost during fights and after the Uprising.

One would do their best to organize military attendants at soldiers' funerals. In the first days of the Uprising a unit's command usually participated in a funeral ceremony, together with the dead person's comrades in arms. In a later period, because of safety, such a ceremony was shortened till a minimum and necessity to spare munitions had an effect of a rare salutes. It so happened that a funeral drew the enemy's, especially aviators', attention to itself, and they would shoot the gathered people.

a funeral of a killed insurgent in the courtyard of the Warsaw Institute of Technology Architecture Department in the Lwowska street

Predominantly one of soldiers-assistants by a burial used to utter a few words, a chaplain would say a short prayer, and subsequently a grave was buried. On a tomb a cross with a plate or a piece of paper with personal information about the dead was put; sometimes the dead's helmet was hang on the cross. As time passed by, more often common graves for few killed soldiers from one unit were prepared. Funerals of civilians were organized without military assistants; however, if no priest was present, a military chaplain presided at the ceremony.

As number of casualties was increasing badly due to air raids and bombardment, the killed started to be buried in common graves. More and more often such a common grave became ruins of houses out of which one could not take dead bodies; at the time people used to put a cross with appropriate information there and a priest said a prayer for the dead.

At the end of the Uprising there were so many killed people that one could hardly cope with burying the dead. Sometimes it happened that the dead bodies were lying for a few days in heat before they could be put in the ground. Lack of appropriate tools was often a problem as stony hard earth needed axes to be used. Basically soldiers and civilians were not buried in one tomb. A common grave became ruins of homes which had buried both its inhabitants and soldiers. Also in hospitals, whenever there was lack of time and possibility to organize separate funerals for everyday bigger number of the dead, military men and civilians were buried in common graves.

Without funeral ceremonies and a priest's company, dead bodies of thousands Varsovians killed by the occupant in the retrieved districts, especially in Wola and Ochota, were buried in mass graves.

In the course of the Uprising also joyful feasts happened. Many young insurgents decided to get married. Chiefly young insurgents led their fiancÚes to the altar: scouts from amicable scout teams, students who worked together in a hospital, newspaper carriers, soldiers and nurses or liaison female officers. Most often bridal pairs came from one unit.

The District Headquarters issued a special Order 19 Point 4/IV regulating a matter of marriages on August 18, 1944:

"In relation to facts of contracting marriages by people who belong to the Home Army I am arranging:

1. Regarding hitherto contracted marriages one is obliged to send to the Ministration Command-in-chief accurate reports including persons' who are getting married names, a civil address and present assignment to an unit as well as to give a priest's blessing a given marriage name, as well as to note a church authority entitled to give their blessing.

2. In the future, before dispersing the marriage chaplains are ought to keep in contact with the Ministration Command-in-chief in order to obtain a proper decision. If such contact is totally impossible one should lead those who want to get married to the nearest Roman-Catholic parish."

A wish to get married should have been notified a unit's command-in-chief who would subsequently inform a chaplain. In the event of people under age, a Dean's or a parent's agreement was also required. Due to fighting and difficulties in communication with one's family it was not always possible, though.

Despite this disposition the war-time situation caused that chaplains had to make decisions of the sacraments on their own. During the Uprising at least several dozen marriages were contracted, although no evidence confirming this fact was preserved. Fr. Dean "Biblia" himself dispensed them a dozen or so, among the others a subsequent famous "Courier from Warsaw" - Jan Nowak (Zdzislaw Jezioranski). A contract of marriage used to have a great religious, social, family and lawful significance, especially in a case of death of an insurgent leaving a widowed wife. Marriages were contracted in churches and chapels and even in hospitals, basements and private homes in the Old Town, Mokotow, Zoliborz, Powisle, but the most of them - in both parts of the City Centre.

an insurgent marriage in the "Kilinski" battallion in the Moniuszki street number 11

In a small hospital in the Old Town there occurred a wedding of a "Parasol" battalion command-in-chief's substitute Second Lieut. Jerzy Zborowski "Jeremi" with a wounded liaison female officer Corporal Janina Trojanowska "Nina"; in a garrison church in the Dluga street - a wedding of Lidia Kowalska "Akne" and Krystyn Strzelecki "Zawal", who both were conducting sanitary authorities of the "Parasol" battalion.

A big problem was to get wedding rings. They often had to be borrowed, for example from parents; one was trying to get them in exchange for, say, a box of tinned food from airdrops. In such a way Lieut. Zdzislaw Jezioranski "Jan Nowak" and his wife-to-be Jadwiga Wolska "Greta" obtained their copper wedding rings.

Bridal pairs used to get married in clothes they had been wearing while fighting. Brides sometimes were lucky to get some white shirt. A bouquet was often made out of petunia which were commonly growing on Warsaw tenement-houses' balconies. In these ceremonies friends and colleagues from the same unit or a scout team took part the most often. Sometimes wedding witnesses had to be replaced at the last moment, before the very ceremony, as they had just been called to action. Information about the marriages was published in insurgent press.

During the Uprising duties of the ministration service were performed by over 100 chaplains. Apart from them also other priests served, and nuns co-operated with them. The Evangelical-Augsburg Church had previously joined the insurgent fight.

Some chaplains made a highest sacrifice of their life. About forty chaplains died like soldiers, were killed, or were murdered. Other priests, friars and nuns shared their fate, too.

On August 2 in Mokotow, in the Jesuit monastery in the Rakowiecka street, SS soldiers shot and killed with grenades 35 persons, including lay brothers and a dozen of civilians. Among the others, father superior Fr. Edward Kosibowicz fell there. The Germans put petrol on the dead bodies and burnt them.

On August 5 in the St. Wawrzyniec church on Wola SS soldiers shot by an altar Fr. Mieczyslaw Krygier, a Home Army chaplain and a "Caritas" chairman. On August 6 Fr. Kazimierz Ciecierski, a Wolski Hospital's chaplain was killed together with Prof. Dr Janusz Zeyland and Dr Marian Piasecki.

On August 6 the Nazis rushed into the Redemptorist monastery in the Karolkowa street. All 30 friars and lay brothers had been led to the St. Wojciech church and then to an area of an Agricultural Machines' warehouse (the Wolska street number 81) where they were executed.

Among more than 350 victims of a murder in the St. Lazarus Hospital (a branch in the Leszno street) in Wola there were 7 Benedictine nuns.

On August 8 in Moczydlo the Germans shot Fr. Roman Ciesiolkiewicz and two vicars: Fr. Stanislaw Kulesza and Fr. Stanislaw Maczka.

On August 11 in the Wawelska street in Ochota ruffians of SS-RON unit executed Fr. Prof. Jan Salamucha "Jan", a dean of the Home Army IV Ochota District.

On August 12 the Germans killed a Salesian priest Fr. Glab.

On August 30 Fr. prelate Walery (Walerian) Ploskiewicz, a chaplain of a front-line insurgent hospital in a building of the Holy Family of Nazareth order's nuns in the Czerniakowska street number 137 died. He was shot by a German soldier escorting a group of civilians after the hospital had been occupied, at the moment when Fr. Ploskiewicz returned to take a breviary.

Having occupied an insurgent hospital in Tamka in Powisle the Germans shot this institution's chaplain, Fr. Jan Czartoryski "Ojciec Michal", a Dominican friar. Although he could have saved himself, he did not want to leave the wounded that he had taken care of. He was murdered together with them.

On September 23 in Czerniakow, together with 30 Home Army and the Polish Army soldiers (a landing operation from a Prague side), Fr. Jozef Stanek "Rudy", fell on the enemy. The unit's command-in-chief was executed whereas Fr. Stanek - hanged on his own stole.

Fr. Jan Czartoryski "Ojciec Michal" and Fr. Jozef Stanek "Rudy" were beatified by the Pope John Paul II in the year 1999 among the group of 108 martyrs of the WW II.

Several priests died like soldiers while curing of souls on a battle-field. Others died under wreckage of bombarded churches, insurgent hospitals and buildings where chapels had been created. Dozens of nuns shared their fate. Lots of chaplains were wounded, some of whom very seriously.

An attitude of insurgent chaplains and the whole priesthood was appreciated by the Warsaw Uprising command-in-chief. Five chaplains got a promotion to a function of a parish priest; fourteen were promoted to the rank of superior chaplains of the war-time. The Jesuits: Fr. Maj. Jozef Warszawski "Ojciec Pawel" - a chaplain of the Home Army "Radoslaw" concentration and Fr. Tomasz Rostworowski "Ojciec Tomasz" - a chaplain of the "Gustaw" battallion in the Old Town, were awarded Virtuti Militari Crosses.

Fr. Jozef Warszawski "Ojciec Pawel", a chaplain of the "Radoslaw" concentration

29 chaplains were decorated with the Crosses of the Courageous, one was awarded the golden Cross of Merit with Swords, and fourteen - silver Crosses of Merit with Swords. Chaplains received many awards after the war.

Chaplains were on duty till the end of the Uprising. In the City lost in both fight and chaos they reminded that human dignity put one under an obligation. To the best of their abilities, priests tried to organize religious life for the civil population being expelled from Warsaw. Priests of the St. Wojciech parish in Wola, where the Germans gathered inhabitants of the whole district in August, would hear confessions and give the Holy Communion all days long.

After the Uprising capitulation, in a passing-camp Dulag 121 in Pruszkow the religious service was performed by the Pallotine friars. Evacuees who found themselves outside the Pruszkow camp, were given priestly care by ministers of those parishes where they had found a temporary shelter. One can find the information in these parishes' records. Priests and friars went to the Pruszkow passing-camp together with those inhabitants of Ochota, Wola and the Old Town who, having been expelled from the capital by the occupant remained safe.

Inside the camp ministration work was continued and its organized forms had been visible since August 18, a day when Bishop Antoni Wladyslaw Szlagowski, supervising the Warsaw archdiocesan since September 1942, inspected the camp. The Bishop successfully took care of deliberating nuns, priests as well as old and ill people. He appointed a Pallotine friar Fr. Wiktor Bartkowiak a camp chaplain. In his work helping hands were Pallotines: Fr. Jan MaŠkowski iand Fr. Marian Sikora. Not only did they cure of souls; the friars also aided people financially, helped with joining families, they also strove for food and medicines. The priests remained in the camp till its liquidation in December 1944.

After the Uprising had surrendered, ministers left the city together with the army and the capital's inhabitants. Fr. Lieut.-Col. Stefan Kowalczyk "Biblia" and five regiment chaplains were taken prisoner as insurgents were, in order to minister in Prison-Of-War (P.O.W.) camps. Other chaplains were given certificates of release from an obligation. Some chaplains were lucky to leave the surrounded city for safe places. Fr. Maj. Waclaw Karlowicz "Andrzej Bobola" - a chaplain of battalions "Gustaw" and "Antoni", and then of an insurgent hospital in the Dluga street number 7 - having been evacuated through the sewers from the Old Town to Zoliborz - became a chaplain in Kampinos units.

A new Armed Forces' chief chaplain in the country became Fr. Sienkiewicz who stayed in Pruszkow. And in October 1944 was approved by Bishop Gawlina. Fr. Stefan Kowalczyk came back to Poland after the end of war in 1945. He died in 1957.

For three post-capitulation months the occupant was systematically destroying buildings in particular districts that survived the ravages of war. This was how an insane Hitler's plan to erase Warsaw from the face of the earth was being realized. More than 70% of buildings in most city districts were ruined.

Small chapels and home adjacent altars became a matter for special hatred of the Nazis pacifying districts one by one. They shared a sad fate of burning and destroying tenement-houses. The capital's restoration in new political reality, in accordance with new town-planning trends, aimed at unifying grounds and demolishing old buildings. Many small chapels remaining after the war were taken apart. Vast inner migration of the population did not favour their reconstruction, too. Up to present day just few survived, being a unique testimony of those times.

At the beginning of the year 1945 its inhabitants started to come back to their dead city. After the end of WW II insurgents set free from P.O.W. camps started to come back, too. At once an action of transferring the dead bodies from improvised graves and little cemeteries in the Warsaw squares and streets to proper cemeteries was undertaken. Insurgents-survivals would exhume the dead bodies of their comrades in arms and with a helping hand of chaplains and other priests - transport them to the Powazki Military Cemetery.

And in separated parts of the Cemetery sections of particular insurgent concentrations and battalions came into existence. Insurgents killed in Wola, Ochota, the Old Town, Zoliborz, Mokotow, Powisle, Czerniakow, and the City Centre were consigned to their soldier graves, next to each other. In the middle of the insurgent grave section a simple stony obelisk was raised, with the Virtuti Militari Cross and an inscription "Gloria Victis" - "Chwala Zwyciezonym" on. Later on, thanks to efforts of combatants and their families wooden crosses were replaced with stony ones. Graves of each unit had the same shape, and often monuments being a remembrance sign of particular concentrations and battalions were added. Only in the Grey Regiments' cemetery section birch crosses remained, as before, the same as being stood on partisans' graves.

There is one another cemetery where one can find graves of the Warsaw Uprising 1944 casualties. This is the Cemetery of the Warsaw Insurgents of Wola in the Wolska street number 174/176. The graveyard originated in the year 1945. A dozen or so tones of ashes of the murdered and burnt inhabitants during the first days of the Uprising in Wola were put in mass anonymous graves. Insurgent graves are also situated there. As a result of a willful activity of the then government they are not organized in such a well-ordered way as in the Military Cemetery. A monument "The dead - Invincible" overlooks the cemetery.

Insurgent graves of both cemeteries are a lasting historical evidence of those times. On August 1, annually, in both above-mentioned places, patriotic manifestations happen in which next generations of numerous Varsovians and unfortunately a systematically decreasing group of living Uprising 1944 participants takes part. In these celebrations representatives of the priesthood always participate.

Traditionally, since time immemorial, an attitude of Polish priests consolidated the society; it strengthened the sense of patriotism and human dignity. At the occupational time, as well as in the previous difficult historic moments the priestly service guarded the nation against denationalization and loss of the own dignity. Consequently, thanks to its determination and perseverance, it did contribute to regaining independence and the whole freedom of Poland.

on the basis of materials coming from:

"Wielka Encyklopedia Powstania Warszawskiego"

and a book

"Powstanie Warszawskie 1944 - Sluzby w walce"

by Romuald Sredniawa-Szypiowski

edited by: Maciej Janaszek-Seydlitz

translated by: Monika A│asa

Copyright © 2010 Maciej Janaszek-Seydlitz. All rights reserved.