Barbara Bobrownicka-Fricze,

nickname: "Olenka", "Baska Wilta", "Wilia"

sergeant Home Army

Group "Rog" from the Old Town,

Battalion "Boncza" 101 company

POW nr 141503, Stalag VI-C Oberlangen

Uprising Witness Accounts

Nurse's diary

|

Barbara Bobrownicka-Fricze, |

From a certain period of time, we've been listening to the news on German's defeat in the battle of Stalingrad. And we finally saw them in Warsaw. They were withdrawing. Four years ago they had entered the streets on whirring motors. They had carried along their arrogance, contempt, violence and awareness of their own force. After those four years they were coming back tattered, wrapped up in bandages, those more severely wounded on peasants' carts. They were shuffling their feet. Without raising their heads, maybe they didn't want to face our joy. In the meantime, when everything started to fall down for them, we were ordered by the commissioner of the capital to get 100,000 of young men to dig trenches. The occupants could've annihilated the whole capital Home Army with this very command if only Warsaw community had followed it. The youth, who has undergone the underground training for four years, were waiting for commands from their own commandants.

I was a communication soldier before the Uprising. The day before its outbreak I was given a long list with the names of all people who I was obliged to inform about a date and a place of the gathering. It started off. I had a bicycle (very heavy one), which made it easier for me as my addresses lived in different, often distant areas, on higher floors, without a lift. I would carry my bicycle up stairs. It was beyond the strength of the undernourished girl, but it was completed. At the end of my tether I would return home in Zoliborz district.

On the following day, in the afternoon, young people were rushing through the streets. Only few of them were lucky enough to carry a weapon hidden under their clothes. All the people would carry some small packages. It was food for three days. The whole uprising was supposed to last that long. They would disappear in front of our eyes in the streets or inside the trams. There was a complete deconspiracy. Total amazement - so there are so many of us.

My first insurgent post was placed on the Dabrowski Square 2/4. In the inside of the tenement houses, which were quadrilaterally situated, was founded high, multi-floored building. It was where our aid post and the little hospital were located. We would enter silently, one by one through the gate, just not to draw attention and not evoke any interest of the occupant. And we've made it.

There were people inside the building, already waiting for us to lead each of us separately to the appointed posts.

Total surprise on the scene: I got to know that I was appointed to be a nurse. Truly speaking, I had gone through the training, but I wasn't kind of a diligent pupil. I would lose my mind at the sight of blood. Order is an order. Nobody had predicted a withdrawal. I reported my arrival to my commandant. It was Joanna M.D. - a dentist. This charming woman gained me and trust and sympathy from the very moment.

Inside the previously furnished post were 24 nurses. I didn't know them, but I felt as if I were among friends - the fight has already united everybody long time ago.

There was a little hospital with a doctor in command.

There were no boys in the site and one could hear none of them. It began. First shots made us aware of the fact that they were there, they stayed awake. Few of them had a weapon. Most of them were hoping to gain the weapon during the fight. Only few of them could fight in the first hours. They would return to the posts totally worn out. They would fall asleep with guns under their heads. They couldn't part with them even for a second. We were trying to help them.

We're dragging out mattresses from abandoned flats. Boys went to panic, hardly did they lay their heads down they would get up at once to return to the forsaken posts.

Ladies from the P. Z. (Help of Soldiers Organization) attack me- here that I'm bossing around, that everything is illegally arranged. So it turned out that I'd illegally dragged out mattresses and boys were illegally sleeping on them.

However, doctor Joanna, beloved doctor Joanna allows me to do everything, and it is her who's in command here. She is alone working from dawn to dusk, even longer, always smiling, and always happy.

There's the second day of the fight. It's very hot on Marszalkowska street. It was all under the fire on the part of the German army. Our boys stand on the corner of Prozna and Marszalkowska street. The fire is too strong - the commandant of the sanitary post and a doctor are afraid to dispatch nurses. Despite the situation, we're going. One should pass the Dabrowski Square. There's no cover. German soldiers have excellent visibility. Raging, fatal bullets are whizzing in front of us, behind us and under our heads. They rebound off the pavement and the walls of the tenement houses, under which we run bending as low as possible. I don't believe that they will reach me, but I'm terrified of sort of muffled, satanic fury of bullets. Boys, crawling, evacuate the wounded on their back through Marszalkowska street. One of them crawls alone. He stopped- they shot him twice. We didn't manage to get to him.

The Pasta campaign. There's a dark night and infernal fire. The Pasta is like a bastion towering under the uncovered street. Germans see us very clearly. How should we set about it? There is no time to ponder. There's a lot of injured. We're working without a break. We have a sanitary post at a large, dimly lighted room. They bring us the nurse with a head injury. We carry her into a room. Her eye is outside of her face. She was so pretty. We put a pillow under her head. A doctor is here. We rush into the street again. Our hands are sticky with blood. There is a groaning of the wounded around us. They sit, lay inside each gate. We follow the voice of the injured people. They are patient, calm - they trust us. German soldiers light up the streets on which nurses are running on the sly with the stretcher. Keeping as close to the walls as possible, as close to the ground as possible, as fast as one can from whizzing bullets. There's no cover, no time to think about it. Just to make it to the corner, it's where we lose the fire. Hurry up, hurry up. We have to return for the next. We reached the spot going through some holes, piles of sawdust.

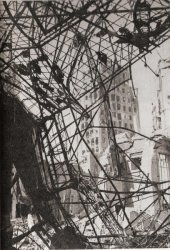

Budynek Pasty (fot. Sylwester Braun)

We hit Marszalkowska street. Boys, crawling, evacuate the wounded ones, who lay on their back. The third one crawls alone. The fire is directed at him. He stops, we wait. He doesn't budge. We don't know if he's lost his strength, maybe he's fainted, maybe he's been killed. We can't get to him. Germans had set their mind on him. Maybe it'll get dark. I didn't get to know what had happened to him.

There are missiles brightening up the battle site from time to time. And then a towering building emerges on the street. How to get to it? We are left only with the uncovered street. This is our only pathetic armament. It's only the fraction of a thought. There's no time. We're back in the street again. There is a groaning of the injured around us. Our hands are sticky with blood. Wounded people sit or lay on the ground. Groans penetrate into our souls. They are patient. They wait for their turn. In the darkness, we try to help those most severely wounded. It's not easy as they don't already groan very often, don't call for help. We run into the street with the stretcher. Germans lighten up the place of the action. And there are missiles again, and again and again

Bending ourselves, we run almost touching the walls, as fast as we can, just to lose the fire, just to get to a corner. We lose the fire. There are some holes, heaps of planks and sawdust. We finally get to the post; someone is taking a wounded back. We run back again. There are ceaseless shooting and explosions. The building of the Pasta, left unmoved behind us, appears in the darkness as a mockery and perishes in the night, even darker after the missile extinguishes.

The first defeat - there is so much suffering. It has lurked somewhere in us. Silence, silence. And there is only doctoring Joanna, who asks, understands and we're somehow a bit relieved.

Misfortunes come consecutively. Planes have arrived. Bullets rushed diagonally into the hospital rooms from the deck weapon. During the injection to our wounded woman from Pasta, the chief doctor got shot in a heart-death. He was trying to catch his breath with a tongue, the last effort, the last aspiration with saliva as his eyes have already turned white.

This is so hard. We talk about him, we can't do anything else. He gave me morphine injection to my tooth. Besides, we spent the whole evening telling jokes. We had fun. It was yesterday.

The evacuation of a hospital of the PKO on Swietokrzyska street. Germans have the reconnaissance of our posts. Volksdeutches imprisoned by us escaped yesterday.

We move our dressing room to a shelter to protect ourselves from the firing coming from the deck weapon. We've cooled down; all the injured is in the safe place.

There are planes again.

Everything's falling down. I was on the ground floor when into the gate, next to the basement, which had been occupied a few hours earlier, rushed a bomb in a slant way. Everything's collapsing, burning dust angrily penetrates lungs, through the nose and open mouth, burns eyes. Horror overwhelms the essence of a human being. Frantic desire to run away. Where? It's dark as in the night. Ah, it's so hard. Immobilization, helplessness. There are moans of the wounded nurses. Suddenly there's a rustle of the water. The pipes in waterworks start to crack. Water from above is flooding the basement. There's an unconscious terror. It grows darker. I already know nothing. To escape- only this, nothing else. I can barely hear wheezing voices of the sinking people.

And suddenly there's a light. Stairs, the stairs which don't collapse. I can't run away any longer, they catch me. There are some drops, unnecessary. There's a terrifying brightness. They explain something to me. They didn't hear shouts, hoarse voices, hastened breaths, rustle, gurgling water. I shrank myself in pain. I go out, a daze, what a horrible passiveness. Everything is fading away as if behind a wall of fog and fear. Why those stairs don't collapse under me, why is everything not falling into an abyss? Why are people yelling? Maybe they need some help? Maybe I should help them? This is such nonsense... emptiness...

Question out of the blue; where's doctor Joanna? I keep asking. There are a lot of people. They are putting out the drowned girls.

They saw her, so she's alive. I dart into the shelters. I'm searching for, I must find her, and I do.

I'm afraid, oh, how much I'm afraid of shelters. I'm struggling with myself. This is terribly stuffy, crowded underground. The view was hair-raising. I feel the numbness of my hair cells. (So it's really not only in books). I can't find her anywhere. I come back.

Rescue action keeps going. There were crashed, terrifying, naked bodies, bloody human remains, deformed faces, sweet scent of blood. The insurgents keep working; there are more and more dead bodies. Doctor Joanna - with a normal face. Thank God she didn't suffer - she deserved it.

I was left alone. Everybody from my sanitary department is dead. New order, I don't even know myself from whom.

The second post is a shelter. I don't have any specified appointment.

What a terribly narrow passage between basements' corridors. Fear shows its tremendous teeth from obscure labyrinths. God, why is there no way out? Embraces of a duty are tough. Scarcely did we enter in - the air raid again. And it is again on our house. There are so many bombs. Plaster is falling on our heads, black, merciless dust. Lights are turning off. And there's one bomb more, and another one. Walls are collapsing. Terror. Feeling of horror overgrows the strength of a man. To escape - but where? Not to exist - but how? Pressure of holding on, what an endless atrocity. We got out finally, having escaped from being buried alive.

There's the next order. We must wait. Next shelter. There's nobody from my department. I can't do it anymore, I'm suffocating at the very thought of getting into a shelter. I'm standing on the steps of the PKO. Hundreds of people go to the underground. I can't, I can't. A department passing by is grouping and calling: "Starowka" (Old Town).

There are my people. (For the time of the uprising I was delegated, at my request, to doctor Joanna). There is Marysia. (My Sister, Maria Bobrownicka - a nurse, she died during the first days of the uprising).

I've chosen. I'm running away to the Stare Miasto (Old Town). I'm at Mrs. Jadwiga, for whom I stepped in during the sanitary course for girls. All familiar faces and there's only Marysia who is not present. I came one hour too late. They went together with Irka to Zoliborz district to get some bandages. (They both died on their way back while passing the Gdanski Railway Station).

Our sanitary post is at 5 on the Market, on the first floor. Peaceful haven. I don't need to struggle with myself. Only those tiring nightmares. There - combat, here - calm, oh, that awareness. You could've done the other way - you've chickened out!

It's already Saturday. So, I've been taking a rest for a couple of days. Life goes on as usual. There is common traffic on the streets.

Through the Market (Rynek), they lead a woman - a spy. She's screaming, crying, begging for mercy, kneeling before the soldiers. I can't stand looking at it, a feeling of despise, how could a man humiliate himself like this? It's disgusting.

And even if I'm wrong - I don't want to think of it.

There're the sun and peacefulness. I'm regaining strength. A world starts to appear from beyond the almighty indifference.

Zdjęcie lotnicze Starego Miasta wykonane na dwa miesiące przed wybuchem Powstania z pokładu niemieckiego samolotu rozpoznawczego. Widoczny Rynek.

I've got my guarding group. All the the nurses are older than me (of age above 30).

First planes appear above Starowka. First bombs. Nurses!!!

We're on the scene. The stretcher. Quickly.

There is dust, fume, the crowd of people, despair, screams. Keep together, one mustn't get lost. The collapsed house, it buried people under debris. Nobody would expect this. People are running around in despair, thronging, they won't let us work. Their children, wives, husbands, the whole families are under debris. We have to be merciless towards them, otherwise we won't handle the situation.

I can feel something weird going on with me. You can't let yourself be overcome with despair of those poor fellows. I comfort them, treat them with a few drops of valerian, and explain to them. There's a new form of the fight, yet unknown, the fight with oneself in the first place. This is the only way in which I can make the rescue action quicker.

Our people and civilian population are excavating the buried. Faster, faster!...

Is there any more buried, can anyone hear moans? God, how is everything dragging in spite of the frantic men's hands, hastened breaths, faces covered with sweat of those throwing away bricks, planks, whole piles of the walls? They are bringing out people covered with dust, who are most often unconscious. We're looking for the signs of life, faint breaths, quiet pulse, and every little spark, which makes it possible to save a man. The fate of the children is the most horrific one- those little bloody bodies.

So they've started to occupy Starowka. My conscience pesters me a bit less, for there's much less time to ponder.

Marysia still doesn't come back. I'm worried about her. She was so courageous, where would that lead her to?

There's less and less singing at our post. Everything has just begun here. Above all, one has to come to grips with each other. I've already faced it. Is everything becoming obvious?...

What a little creature is a man in the face of a collapsing wall. Like a defenseless, ruptured house.

I'm at Brzozowa street 2/4, this is a place of my activity.

Germans are bombing more and more. They've set their minds on the Market.

Sanitary station moves to Kilinskiego street. The fear appears again. I'm overtaken with rage; will it be he or me who takes control over me? I stand to make a report. I ask for being left together with the department. Cold, icy eyes of the commandant (I've been her favorite so far). I'm explaining that this is too far, and in case of an arterial bleeding I might not do it on time. As I'm speaking my fear somehow dies away.

She ordered me to wait for a response. I rush to her superior and I get the approval of everything I'm asking for.

There's anxiety among boys. They were certain of their nurses. What will happen with the injured, who will bandage them? To call for guarding groups from ,,the rest of the world"? What are these explanations for? They know that this is fear. I'm announcing that I stay. They are over the moon. I'm joyful.

There's another call from my commandant. This time it's the order to move to the Market under 2. We have to occupy an abandoned place (there was a bar belonging to Volksdeutsche before the uprising). Besides, it's an order, no comments are necessary. I'm begging, asking, though it's very near my boys. I'll be visiting them - the voice of my commandant is tough, her eyes stay cold.

I won't give up.

Transfer. Boys don't spare us the worst words.

- You've chickened out. Your own skin - this is what counts the most.

What a heavy load. I'm trying to explain. They don't want or they can't understand.

That's how we've become a lonely, guarding the group to which, honestly, nobody would acknowledge. Our quarters are spacious and comfortable. There's even place to sleep. Ground floor from the side of the yard, vaulted old-town ceiling gives us the feeling of safety. We clean, polish the floor, arrange a clean and aesthetic dressing point. Everything's ready to go without delay in case of a call. The only thing we don't know yet is what we will eat.

I have to write something about my guarding group, and particularly about my two girls. I may start probably from Miss. Kazimiera. She's a professional nurse. Her education put her first when compared with ours. What are we, who had finished aid courses, what are we, without education? I've already felt the burden of responsibility and pangs of conscience because of my education shortcomings for many times. In this situation, none of us dare to say anything about sanitary issues. It resulted in the enormous number of instructions, and what's worse, her ironic smile showed us her great, healthy teeth, able to uncover the most secret knowledge, let alone our ignorance. Miss Kazimiera was a great patriot, and she would spot serious shortcomings in this filed as well. She was never short of points for trainings, upbringing, criticizing. Her demands on cleanliness were the toughest to bear. She would even make scenes. The worst thing of all was that she would always turn to me to approve of her demands and opinions. I would resort to all my diplomatic skills to avoid problems, finish dispute, trying not to hurt Miss Kazimiera, save the tranquility and good atmosphere in the quarters which were always a place for the rest. I barely made it. For when I raise my eyes, I would meet her eyes filled with such an irony. I was helpless.

And yet she, Miss Kazimiera, had a very good heart, was loyal, very dutiful, a true expert. She's the nurse with a calling. Still, she was a real nuisance, an individual being destructive through her dissatisfaction. (It might be because she was already 36).

The second one, Stefa, was, to be true, very young grandma. She's always happy, energetic, and ready to help. Civilian population was under her charge. Hence, she was called an angel. Hard-working, reasonable, always satisfied. It was her who I could always rely on, ask to do work for me, when too much work forced us to divide it, in order to rise to the challenges, among the guarding group.

They all came from Marymont and Praga districts. I had to keep them under control for I would guide them under bullets and I had to be sure that they would make it. It only happened once when three of them withdrawn from under the fire.

It didn't happen again even in front of guns or mortars.

Leading them to the action, I would not look back but none of them dared to stay. However, apart from that it's not easy to carry girls under bullets. One must not even for a moment forget about reason and prudence, that's why I preferred most going by myself or with Stefa.

I've neglected my writing. I have to step back. We've settled down so now we may do some solid work. On the next day the commandant comes personally to announce that from this day on Miss Kazimiera will be our commandant of a guarding group (on the account of her qualifications). I was delegated to take care of making dinners. So it's degradation!... This is because I had stayed on the Market.

After commandant's departure, everything remained the same. Kazimiera didn't feel like being our commandant and nobody expressed willingness to obey the order. And the day was, as usual, full of work. We've been carrying the wounded from the very morning. We don't have the strength to fight with our own tiredness. And here's another challenge. A rocket has fallen into a yard, killing one woman and wounding two men. And there wouldn't have been anything special about it if it hadn't been for the results. We're running, the whole Market is under the fire of KB, RKM and additionally rockets. We can't wait, there are serious injuries, heavy bleeding. Our way back is the worst one - bending, running with the stretcher, even though our hands had been in pain before, as well as our legs and back were painful from lifting loads beyond our strength. Wounded person is often unconscious, very heavy, and we were not the kind of strong women. Just to add the undernourishment, debris under our feet, on which, while running to save a man, we would get to the hospital under the "Krzywa Latarnia" ("Crooked Street Lamp"). Hands and legs fail us. There's another injured. I send my girls back to the quarters. I make a final effort - I take out civilian population. They take the stretcher - the injured civilian...

And the attack keeps going on, so it's not the end.

Germans set the Cathedral on fire. It's hot. At the same time two nurses from the "Kilinski" battalion reached our quarters with an order that my girls should go and carry water. (Without even telling whom the order was from). They got the answer to do it by themselves. I didn't know the story until the evening, when I was back at the quarters. I'm a bit disappointed that it was just they who had refused to help. I knew how exhausted they were.

On the following day the commandant comes. She doesn't want to hear any explanations. She strips off their armbands. Let them go where they want. Boys are listening in amazement. They need no explanation. They comfort me. They won't let girls die. It has to be explained without a doubt. Two scout-girls were delegated to me - Basia and Slawka. These, on the contrary, are roughly 17 each and are not afraid of anything, at least at first glance. Basia is the worse one, as if she wasn't aware of a danger.

And here, in the meantime, house after house fall into debris, here the fires brighten up the nights. And here heavy artillery from Praga tears cornices and walls off, smashes everything what's already been crashed, digs forcibly in everything what's been destroyed. And above all of this, there's a hateful rattle of planes. Tank from Krakowskie Przedmiescie street is striking at us. As well as rockets do. There's an ominous rasp of "szafa" - "cabinet" (ironic name of German heavy demolition rocket shell which sounds on start similar to scratching cabinet's doors - German name Nebelwerfer). No-one of us counts how many torpedos will be launched at us. For the number of rasps equals the number of shooting series. And there's still a shell-proof train at the Gdanski Railway Station, sending us bullets, which tortured air gives us back with a mourn. In the abandoned houses' windows snipers are installed, the saboteurs - it's ridiculous. We bandage the army and civilian population. We are called for everywhere, and there are only three of us left.

Fumes hovering over being mercilessly bombarded Starówka. The photograph taken by Sylwester Braun from the Prudential building.

Hence, we have to make use of the aid of civilian population who never refuse to help. I'm leading the civilians through the Market, who carry a colleague. There are about 7 rockets falling around us. I rush to flee. I rush into the gate. Civilians carrying somebody injured follow me. They put down the stretcher. Wind scatters the fumes. Wounded man lies alone on the stretcher. I've set an example. How good that none of my girls was here. And maybe I would have mastered my fear in their presence.

I have to move back a bit in time. I thought that I would never write about it, that there were no words in any language in the world which could be apt at that. I can't get rid of those images. Maybe I will feel better when I write it.

I came back to the 13'th day of August. It's a sunny day. One of the nurses rushes into the quarters. There's a tank on the Market, we run outside. It's going. At one moment people pulled down a barricade as if she'd been blown off. It passed beside us. The barricade took its place again. Everybody's happy. We are back at the quarters. Walls have trembled. We all know and are able to distinguish flawlessly between detonations. What is it? There's no answer. We get outside. Roofs, lines of houses have immersed in the dense fumes. I'm running, maybe somebody needs us?

I don't even get to the place of an accident yet, but I already know. The tank has exploded. A time bomb was installed inside it. An accident on Kilinskiego street - there is our sanitary point. I come back for the stretcher. We're running. What a view! It's impossible to believe. I'm contracting with horror. We walk as sleepwalkers among vapors of blood, among dust of collapsed houses which is falling to the ground. What a hateful smell, one can't free oneself from it. There is a mass of human bodies in front of us. Scattered legs, arms, pieces of human body, blood, brain in dust. There are moans, trembles of the wounded, rattle of dying ones. Pools of a blood sink into debris. Pale boys with guns keep an order. Horrible groan...

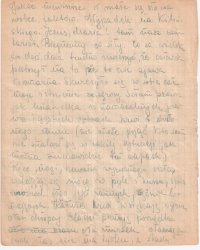

The fragment of Barbara Bobrownicka's dairy, which was being written down during the Uprising. These notes served lately the Author as a basis for postwar work on the Dairy.

Blood, more and more blood, whole pools of blood are sinking into debris. Blood is on the walls of the buildings in the vicinity from which the plaster has fallen off a moment ago. And there's this stifling, sweet smell of blood all the time. It's impossible to comprehend. One can't let yours eyes look at it, for the terror's everywhere, for there are tattered corpses of people, for our legs slip on brain, intestines. One can't stand listening, for the groans emitted from this heap of tattered people are unbearable, for one can think that they are emitted from the inside of our body, from some superhuman, incomprehensible horror. We walk almost as somnambulists, work as robots. What does our aid mean? The wounded, having been unearthed from among the remains and taken to the hospital lay in the long queues to the operating theatre, to the operating table. How many of them will make it. Physicians work without a break using candles only, for the tank's explosion destroyed electric wires. How many of those wounded will make it for their turn in the queue. There is so many of these children, who lay all silent and pale on the ground. They don't even moan, don't cry. Maybe they're already dead. What a horrible wounds. Right beside the injured one missing one leg lays a man - the whole man. Hurry up. He's got both hands and legs, no injuries visible. I come closer, maybe... could there be any sparkle of hope? There are bloody eye holes in the empty skull, chipped teeth.

I'm being overwhelmed with some saving stupor, I stop thinking, and I stop existing. And this is probably a rescue. For I've got to rescue myself somehow.

There are no human feelings, neither fear nor courage - absolute indifference. I lift up the stretcher out of habit. I'm paving my way with my voice, I'm talking to the people who I see and don't see. And it's just a mere sense of duty. And there's the comeback at the quarters after some hours. Painful limbs, a buzzing head. One mustn't let oneself relax. For they also feel the same - my girls.

I order them to eat supper. They reject. However, I know myself by some prompts of the nature that I mustn't yield. I eat supper myself. And even though it was not so long ago I don't remember, what we could eat. But the most crucial thing at that moment was to overcome your nature. And no tear was shed, no complaint uttered. And we went to bed and fell asleep.

Germans penetrate into the Starowka.

Ceaseless attacks become such an ordinary thing that each moment of silence raises anxiety, evoke curious questions.

I was convinced that my sanitary point was a non-conquerable fortress. Thickness of the walls, domed ceilings - they raise trust. Shells would transfer, planes wouldn't hit the target. But this is not the end of the possibilities of human grey matter. There are still "cabinets". Neither of us saw nor knew what they were but we'd already seen the result of destruction, we'd already discovered effectiveness of this operation. And one of them was just making her way into our tenement house.

Windows of my sanitary point were situated just on the shells' way.

And one afternoon there are clouds of dust, fire, flying doors plucked out of hinges in our room. All dressing means stopped existing in the fraction of a second. We were calling ourselves in the darkness to see if we're alive. Slowly, in dispersing dusk, our silhouettes started to appear, thickly covered by brick's dust. We had no time. We had to get new bandages right away. We had to bring our sanitary point to the state of utilization. Girls found a small puddle and with the water from it we washed the floor and furnished everything again. We didn't mind there were no windows or doors anymore. Everything's ready. Following "cabinets" rushed into the yard and everything started again. We didn't give up. There was quite a lot of water left in the puddle. The third time was probably the worst one. We don't know what whirls pushed us to the toilet. Doors are locked. There's a moment of terror if they would open. They did. Each of us was at the different place the moment before the explosion. None of us felt that she's drifting, yet some strength wiped us out and placed all together. No sooner had we come to the conclusion that it must have been this cleaned the floor that had brought us bad luck than for the fourth time. We didn't clean her because the puddle ran out of water. It worked out. They left us in peace. At least the "cabinets" did so.

However, apart from that we're getting more and more engaged in our work. There were more and more wounded who we had to go to their aid right away, change bandages, sometimes just talk to, comfort. For they would appear worn out, helpless. They subjected themselves to our care with such a trust and faith in our skills that we were cheered up. They needed us. We not always had all necessary medicaments. But it was probably here, at ruined quarters, where our caring instincts started to occur. Among those who would come here for a word of comfort, relations started to originate. And somehow this word of comfort would be found. How? Nobody knew that. For almighty weariness reigned. Undernourishment, going to sleep on every place, without stripping off clothes for weeks, in bloody clothes with shattered souls.

Jurek from Brzozowa street came to the quarters. Just to do some chat. He was telling us about his mother. How hard she had been working to enable him to study. It seemed to me that I know this little, tired woman from Marymont district, mother of the big only child with blonde hair and blue eyes. Despite that it was hard for us to listen to that story. We've already noticed before that when one of our boys started to recall his nearest and dearest and his house, he's doomed to encountered misfortune on the second day or earlier. Yet Jurek kept on talking, and his disheveled hair spilled in all directions. And we received the call on Brzozowa street - five wounded. We're going. Descending down the Celna street in a direction of Wisla river. At a moment, I don't know myself where it came from - the anxiety. I sprang my girls to the run. We rushed into a gate - artillery shell, the blast threw us on the stairs (we didn't know that Germans had made a hole in the wall and they had been shooting to individual people). There are the injured people. Big Jurek lies on a table. His brain is outside, there are intestines piling up under his belly, how long will his miserable mother be present in my thoughts.

Everything has its limit. Our sanitary post has been demolished. We move to the basements. We can't collect the injured under bare sky. Air-raid shelter is narrow, stuffy, and gloomy. A paraffin lamp is burning all the time. Dressing means lay on the tiny chair. The lamp dies down from the blast of air from time to time, which, in its escape before the shells, "cabinets", crowds up to the basement, into our ears which bear it with increasing difficulty.

We were welcomed very kindly by civilians, who had been residing in the air-raid shelter for a long time. Yes, they were craving for our care. They needed it so badly, as well as comfort. Where can we take it from? Yet, it would come into being out of necessity. For it was necessarily needed not only for the miserable civilians but we also had to comfort ourselves, we had to show happy face to each other and the others.

And it wasn't easy in the time of weariness, when all around us mocks at our optimism, and maybe from the fear of facing the truth. In such a lack of space one can only sleep on the chair. And so we did, even though it'd been impossible for us to believe that we could do it a couple of days earlier.

There's more and more work among civilians. Immediate aid, given so far, is not enough. Permanent nursing of the burned, injured, bruised, with gunshot wounds, with wounds filled with pus. And it seemed that one couldn't work harder. Dressings of the burned were the worst of all. Non-sticking stinking dressings and lignin full with pus. Unbearable smell, but somehow we would make it. In addition, we would keep smiling at those poor fellows in order not to make them figure out that we're going to be sick. They apologized to us. Those unhappy, innocent ones. Passing through one tenement house to another one would be carried out through holes pierced in the walls, most often on all fours. Oh you stuffy, horrible molehills. But somewhere there, in another air-raid shelter in a row, our aid was needed. Above it all, a world of the war was thundering, rumbling and swirling.

A bomb hit into the basement. It buried the only narrow hole through which people would get outside. We're throwing away heaps of debris. There's a tiny hole. I'm hanging myself down the ladder into some narrow abyss. Through the narrow corridor I'm making my way into the basement secluded from the world. Fortunately - no people were killed. On the narrow couch lay a woman battered by debris. What can I do for her in such conditions? One has to get her out of it. Someone has to move the tons of debris, enlarge a hole. One has to smash enormous pieces of debris, move them from their place, with what, how? I'm telling it to her son. We both know that it's impossible. How is he looking at me? How many of such desperate glances I had to bear? For them I was their last resort, I would become their last defeat.

There's stuffy in here, no air to breathe. I put some bandages, I make some advices and I run away. And there's this fear again.

Morales of civilians in our area are really outstanding. Voices of despaired ones reach us from time to time, but even they put their trust and sympathy in us.

And the Market, beautiful old city Market is just a heap of debris, silhouettes of houses. The remains of old ceilings finish burning. It seems that everything is lost, but the fire still finds quarry for its flames. In the night they can pop up as satanic tongues. And above them - there's the Moon, calm, grand, somewhat pure, as if it was bathed of all dusts of the world. I look and I envy him his space, tranquility, the certainty of his way - me, a little one, filthy with human dust, besieged, defenseless. One cannot allow oneself thoughts like this. It's the first thing forbidden. During the day, when debris is becoming grey, our Market serves as a walking place for pigeons. Among those ruins they seem to be even smaller, unprotected. They come back after each air-raid, after each attack. There are less and less of them. What do they eat? Why they were not escaping? It's good that they don't escape, for if I entered the Market and didn't see any of them, I would be the most solitary man on earth. Surely, I can't tell them my thoughts, but I decide that if I can - I'll pay them back. It's for sure. For someone has to write down the story about old city pigeons during these hard times.

We have to pack up our sanitary post inside the air-raid shelter. We've run out of oil. We can't work in such conditions any more. It's heavy both for us and them. We'll be coming back to them, here in the darkness, but it's different. We know that - both we and they - the defenseless civilian population.

There are two days of relax on Kilinskiego street. I'm not cut out for it. I ask one of the boys to call on me to go to the fortification.

Thus I found myself under the direct orders of lieutenant "Szczerba". I'm on Jezuicka street. It's a small building, near to the fortification. There's a library inside. There are genuine rarities and the smell of old literature. Our time governs different dimensions, different indicators.

For me, it's a new, unknown feeling. I've got the commandant who I can trust. I stopped being a lost nurse, not acknowledged by anyone. I completed my first-aid set with the greater zeal. I found a small closet - the luxury summit. I watched joyfully my bandages, which are placed orderly. They were so clean in this world lacking water and soap. There was a wonderful atmosphere there were unforgettable evenings. People feel well in the atmosphere of common worries and emotions.

About the twenty-third of August an assault troop under the command of a cadet Lesniewski was sent to us from the Kampinos forest. We knew that he was a brave man. He was subordinated to "Szczerba".

The attack. "Szczerba" didn't want to let Lesniewski join the campaign (he was drunk). The cadet put his foot down. He won't let his people fight without him. Our commandant, very nervous, gave the permission. Lesniewski the first one killed. He leaned out of the wall too much. He got shot in a head. There was a very nasty atmosphere. We pity boys who have lost their commandant. They accuse "Szczerba". We defend our lieutenant. We all feel heavy.

The way to the hospital is getting more and more difficult, debris mounts higher and higher. Mounting up with a stretcher and very often under the fire is bothersome. It's hard to understand but somehow we find physical forces. There are already inaccessible places and in such cases we make our way through the houses. The Baryczki's house is the only one left on the Market. And we have our kitchen inside it. There are two ladies from PZ. It's Miss Zosia and her friend. It's hard to comprehend. They are cooking there all the time. Nobody thinks about where they take the water from, which alone has gone from the Market for a long time. We receive porridge every day. As if there were no assaults or no air raids. The debris pours into the kettle and our teeth are crunching, but who would make a fuss about it? Who knows what they're going through there? Who's thinking about how much courage and self-determination are needed to work in such conditions? We don't have time to ponder over it. Each one of us has his own problems which must be hidden even before oneself.

Fire-fighting was the most demanding job on Jezuicka street. We had no tools to do so. Old prints would burn up very quickly, the fire was spreading, and fumes would choke. Germans were at the Kanonia and inside the cathedral. A tank would drive up our post and at the distance of few meters he would shoot into feeble walls, setting fire. We were aware that in such conditions our walls wouldn't hold on any longer. We had to get rid of German soldiers residing inside the cathedral (for which time is it?). Wojtek (Wronski) with Wicek (Rankowski) decide to set vestry on fire. They prepare bottles. Stir's arisen among us. We are all aware of what they dare to do. They are crawling. Wojtek comes as the first. We hold our breaths. We freeze with anxiety. All our thoughts are together with these boys. All the rest stood still. And they are moving forward slowly, carefully, for there is no play with the bottles. And this is probably something we fear most: that they wouldn't brush up against a brick, wouldn't damage a bottle. At least they threw them. There goes the first one, the second, the third. There's no fire. The fifth one... zigzagged tongues of the fire start to spread over the singed log. Will they hold on up there? Will they have enough strength? They are crawling higher and higher. They reach lightly burned logs, embrace them and they liven up. It's on fire. A tension wears off. Being already certain we are observing every new little flame.

The ruins of the cathedral (photo Wiktor Brodzikowski)

An unexpected order arrives. There will be a march out to the Srodmiescie (downtown) district. Some part of the detachments will go through sewers. Some of them will go on the ground, as a cover for the injured who won't make it through the sewers.

There's a strong alert. We set out during the night. There are eight people remaining at the post. I feel awful. Should I come out? I turn back. "Kropka" seems so small to me. She's so vulnerable.

There's a dark, starless sky. We're holding hands in order not to get lost. Muffled voices of troops calling one another could be heard in a distance. Nervousness. They are different soldiers. It would be a massacre to attack at that moment. There's no time to think about these things. There's no time to hear some accusations popping up at night surrendering us as well.

They're calling out our troop. We move on. One boy in front of me falls into an open wardrobe on the fortification. I resist doing the same with all my strength. I've made it but during the struggle, my comfortable shoe falls down into the same wardrobe. It's irretrievably lost. One mustn't lag behind. My one foot is shoeless. And there is only debris, broken glass, scattered planks stuffed with splinters.

We're moving slowly, quietly, by the walls of Miodowa street - it's all in ruins. We're moving faster and faster into some nooks. All of these are familiar but we can't recognize anything. We're going on, or going around, we're moving forward or not. It's impossible for Krolewska street to be so distant, even if we would have to pass it through the unforeseen rubble. The feeling of being lost is growing. Where are Germans? They could hide behind every corner. There are sounds of a ferocious fight. There must be other troops forcing their way through Krolewska street. Weariness knocked me off my feet. We have to fall down to the ground more and more often for Germans launches more and more rockets. Our tired eyes are being dazzled with multi-coloured lights. And when they go out, the darkness becomes impenetrable. Hardly does our sight get used to it, the others start to soar up while shadows of the collapsed tenement houses elongate between our bodies. We're lying next to a bill-post. There are the remnants of posters from the world which had existed not so long ago. Had it really existed and was it for real? The situation is a real puzzler. Scouts set out for reconnaissance. They come back. They don't bring anything with them. We don't know where we are. It starts to brighten up. We're getting tired of tension and anxiety. It's almost grey. We're coming back. We're in a great haste and the emerging light is chasing after us. My poor leg is full of splinters and glass. It's already swollen up. There's our post at least. We're welcomed by embittered casts of the eight, which had spent here the whole night. They are right. How should have we acted?

We get to occupy our positions. We fall into some kind of a half-dream, with which we can't handle. There's the fire again. They've set our post on fire. We're looking indifferently at the ceiling burning under our heads. Nobody stands up. An order from our commandant hardly changes it - what an overwhelming feebleness. It took few people a couple of minutes to drag themselves to take action. How difficult it is for them. However, they somehow managed to find some energy. The number of rescuers was growing up. Blind shells, exploding more and more often, made it difficult to extinguish the fire. We would wake up in the heat for a next day. Again, there's a tank before the building on Jezuicka street, but we're not going to let us burn down. Every little flame is nipped in the bud. However, it's not just a tank, but it's also the enemy's attack, which has already known that he has won. And we, even if nobody says it out loud, we know that we're not going to hold our position. In such a situation a soldier fights in a different way.

A day is full of dispatches. Our "Szczerba" is called also.

We're leaving Jezuicka street in a great hurry during his absence. We're installing ourselves on the other side of Celna street in the corner house (most often we would withdraw while our lieutenant would go to the dispatch). In this haste I forgot about the one injured in his stomach, who was lying in the adjacent room on a table. Nobody wants to return with me. Germans might be already there. "Szczerba" has returned. We've taken our wounded. Germans didn't find out that we'd already gone from there.

Although our new post was placed on the other side of the street, only one house further, it's changed our strategic position. Jezuicka and almost whole Brzozowa street was in the hands of the enemy. We had to place our people in twelve holes from the direction of the street, and there were thirty people left. Apart from KB and PM (submachine gun) we had one LKM (light automatic rifle), which was shelling the Market from the Baryczka's house. And this was done very sparingly for we had problems with ammunition. Next to the fortification, at the exit of Krzywe Kolo street, stand two guys with hand grenades. Cracked walls were bending menacingly over us (who would pay attention to that?). As a matter of fact, our position was unable to be hold from the very beginning. Germans were bombarding us with a stormy fire. At 10 Am we received an order - to hold on untill the evening. The army goes into sewers on the Krasinscy Square. We can't let Germans go in there. We were a covering troop. We could only guess what was going on behind our backs. Time and again, we would find out suddenly that some troop had left its positions without warning, leaving our back uncovered. Fortunately, Germans didn't manage to put themselves in the picture. If they only knew how many forces they had to cope with? If they only knew how many of our people were standing behind these remnants of the walls? In the meantime, panic broke on the Krasinscy Square. There's no way to understand it. There are the same soldiers who one, two days earlier fought for every house, yes, every room. They are threatening their commandants; they want to come down to the sewers in the first turn. There were shootings, people would elbow they way through. Different news reached us and it was hard to believe them. There is calm among us, we still hold our positions. We are aware of the gravity of the situation. We're aware of our role and necessity to hold our post. In this seemingly unreal situation, calm of our commandant was the thing which made us composed.

(It was only after that, when "Szczerba" admitted that he hadn't believed that we would have survived).

It was far later when a saying of colonel Wachnowski reached us that the Stare Miasto (Old Town) was "Saved by God and Szczerba". That was later. . However, before that, one had to hold on through a long day on lost positions. Germans got furious probably. In the morning the last of the standing lonely walls has collapsed covering one of our guys. We had no access to him. Germans have uncovered a field of shelling. Our headquarters was placed at a small room of an almost non-existing house. It was the centre of commanding of our commandant. It was there, where boys would come out to take their positions, communication soldiers ("Kropka" and "Czarna Basia") for reports, with reports, to get ammunition.

"Szczerba" sent me with "Czarna Basia" on the Piwna street to get the ammunition. We were going through many nooks and rubble. Nothing resembles something from the previous day. Every silent patch under our feet would herald the unknown, carry uncertainty, arouse anxieties. And just to add silence to that. I didn't like silence. There was a lurking ambush in it. Where are Germans? Are we going directly into their arms, or maybe they are waiting untill we get closer at a shot's distance. Imagination was working in panic. Each brick, every elongated shadow would tell about our lost position. We got through Rycerska street and climbed on Piwna street through mountains of planks and rubble. There's still silence.

Out of the blue, there's a grenade launcher and it began, as if evil forces had been released from the chain. We squatted in the uneven ground. We can't figure out where they are attacking us from. Is it from all directions? It's impossible. However, everything is hissing from everywhere, shattering, mocking at us being lost. We're seriously frightened; we've completely lost our orientation. What's worse - I feel I'm going mad. Despite this, none of us wants to admit that she's scared; none wants to make up decision to go back. Finally I'll shoulder the burden. "We have to come here later" - I hear my own voice as if someone else had used it - "When it's cooled down" - I know that I won't come back. The only point is to make her unaware of my cowardice. She was visibly relieved too, although she thought that I didn't see it. We went back. I'm making a report to "Szczerba"... He doesn't say a word.

There were no casualties. I was distributing a dinner to our boys. They were so calm and self-confident. We talk in whisper. Germans are at a distance of few meters from our posts. A real tragedy those days was the lack of people. Additionally, we weren't sure if there's everything all right on our back and if any troop has left the post by chance, giving Germans the possibility to surround us. The space we were told to keep up was still to extensive.

I entered the headquarters the very moment when "Szczerba" thanked Wicek Rankowski for having set a house on Brzozowa street 2/4 on fire.

And this was the house where Wicek was growing up, or maybe even was born. He was asking our commandant just to let him to complete the task. While we were withdrawing we had to set everything that was possible on fire to delay the attack of the enemy on terrains abandoned by us. It was about 11 o'clock when we slowly started to withdraw. The civilian population got to know about it. They came to "Szczerba" to ask him not to set fire. Inside this little room the remnants of their property were stored.

- I do feel sorry for you, poor fellows- says our commandant. I see tears in his eyes.

- It's us who feel sorry for you. If there's a need, just do it - answers those wonderful people.

And it's already been a month for them who spent it in the basements, on the verge of doubt and hope, in hunger, darkness, filth, uncertainty of every following hour. What do we know about sufferings of those people? Among alike are our mothers, younger siblings, our... no, one mustn't even ponder the subject.

Following the order of our commandant I move to the Baryczkow's house, which still stands unharmed. Our LKM has its position in its interior. It's the gun which keeps the Market under the fire. Apart from him, there are two KB, on the fortification next to Krzywe Kolo street, a place, where it merges into the Market, leaning against the Baryczkow's house from one side, and on the other on the Barssa's line, which is still defended by our slowly withdrawing fellows.

The Market of the Old Town, the Barssa's side - a pre-war photograph (photo Wiktor Brodzikowski)

It's 5 P.M. Our "Szczerba" is on briefing again. The retreat is directed by colonel "Zawrat". I didn't attend it. I was seating peacefully in the Baryczkow's house under the care of our LKM. Fortunately, I wasn't called by anybody. Fortunately, they didn't need me. I don't even know if I noticed that our gun fell silent about a moment. Until the scream: "Germans are on the Market" galvanized everybody. It isn't until then when the silence of our cover reaches my consciousness. We're defenseless. Germans, I can see them through distance between planks, which are supposed to protect the entrance to our post of resistance ("protect" - ridiculous). And Germans are still cautious, they are still prowling.

Our fellows are panic-stricken. Terror, almost touchable, was rushing us from behind. I've picked my bag with bandages and I ran with the others through the ruins of houses. But after a dozen or so meters I realized that there, on the Barssa's line, are our boys without a cover. They won't defend themselves; they are doomed to be killed by Germans. I started yelling at the running people with an inhuman voice. Nobody hears me. I rushed into Krzywe Kolo street. There's a feeling of horror and despair, numb thoughts. The first to the thoughts is to run and alarm boys. I know I won't make it. I'm so indifferent, so indifferent. It takes a while to feel that something weird is happening to me. I'm throwing away my ambulance bag. I come closer to the soldiers from the AL (People Army - communist formation) post, who I meet as first ones. They probably stand guard. They are all equipped with KB. I order them. I'm so determined that they don't protest. We're moving forward. I was leading them to the lost positions. Fear, that fear again. I didn't give up. I felt as a different person, as if I had grown up in my own eyes, as if all reasons which were leading me ascend me above all other reasons. Ahead of me there are only narrow planks. I can see green uniforms, I can see prowling boots. I walk firmly. I mustn't withdraw. Only my self-confidence is a guarantee that those unknown boys won't take back. I place them next to the three windows. They shoot. Germans were in panic. They run away, fall to the ground, stand up, fall again and don't stand up. Boys, lovely boys, how they can shoot, how they hit the target. I'm with them; I comfort them though it wasn't necessary. How many insurgents had such a magnificent shooting field, such a visible target. I felt as if I'd been a real commandant.

My fellows started to come back with a new weapon. Guys from AL say to me that they have to turn back to their positions. I'm running to their commandant. I explain everything to him. He gives back his boys at my disposal. After that I'm getting closer to the fortification. I can see them; I can see them alive, safe and sound. And they are maybe a bit surprised. I'm shouting under the fortification as if I wanted to shout out my wild joy that I finally see them being secure.

Lieutenant "Zawrat" gave the command of Krzywe Kolo street to Wojtek, and the Baryczkow's house to me. What a feeling, I was a real commandant. Even if thsere's a peacefull atmosphere now. We are looking at the corpses of the Germans. We can see green everywhere. Above scattered in different directions dead bodies, there's one towering: sitting among rubble, comfortably leant against protruding planks.

"Szczerba" came back and a new LKM together with him. I've played my role. Peeping into various nooks, I found a small room on the ground floor, and inside it, unbelievable, boxes with a sparkling water and orangeade arranged to the very top of the ceiling. And we've suffered from the lack of water for a long time. And we couldn't very often wash our hands before and after having put a dressing on.

"Teddy" brought us Panzerfaust which not so long ago was priceless. Now it is useless. I went to hide her. I've met my friends. We're chatting. A little, maybe six- years-old boy's standing next to us unobserved. He comes up to me, raises his blue eyes, filled with tears and asks: - So Germans will come here? I deny quickly, angry at myself that this baby has heard such an improper answer. I'm not going to forget soon a view of these frightened, childlike eyes. In a minute I've heard a conversation of the people from OPL (anti-aircraft defense), who had decided not to put an anti-fire picket for the reason of our presence. I could hear their calm voices, their care for our wearied sentries. I sat on the rubble and fell asleep immediately. They woke me up before the very debouch.

We were marching with silent steps across the street in a direction of the Krasinscy's Square. Residents of the Starowka stand on the pavements. We could guess their presence in the darkness. They were the same people who would show us a great deal of care and kindness through all days. They were standing still. We've given them defenseless, as a prey to the enemy. And now a silence fell between us. How ambiguous the silence can be, the one with which the enemy frightens us, the one which emerges from under our cautious steps to protect us from the common suffering and we only lack the one which would bring us consolation during these hard hours. There's a single voice speaking after a while - "You started, you didn't ask, you're leaving and don't say a word". And nothing more. And no heart has broken in this silence. And there were no more words.

We're heading for the church of Pauline Fathers. This is a place where we'll be waiting for our turn to the sewers. The whole Starowka waits impatiently for its desire for escape. And a manhole is opened only for the chosen ones. We participated at the atmosphere of apprehension. We're leaving in turn. The order: to leave all belongings. There are already whole heaps of them, left by those, who have gone out. And my sanitary bag completed for a long time with such an effort has finally joined the heap. I put carefully my reliable blanket. Even while leaving, I could see it on the very top. As if I had left a friend, it would protect me many a time from the cold of a night, many a time it would hug me in a peaceful dream while sleeping on the floors of different kinds. And it won't be there where I'm going...

As we were approaching the sewer, we would go in Indian file, then squatting and while we were getting closer - crawling. Only few people knew about steps to go down. Mostly, we would fall from the top, fortunately, it wasn't too deep. I fell down as the others did. There's darkness. Ominous rush of water would carry itself inside the acoustic tunnel and fill up everything. Hideous fetor. Wading across ankle-deep water, I'm sticking to my predecessor; behind me the next one is sticking to me. We're moving forward as quietly as possible. We've already known that Germans would throw hand grenades into the manholes, they set the petrol on fire, as well as karbid... One mustn't think about it at this moment.

As time goes by, we're moving with more and more a difficulty. One can't... Oval, low sewers weren't adapted to such purposes. One can't put his stretched leg. What's more, I was wearing a ball shoe with thin heels, which one of my colleagues gave me after I'd lost my shoe on the fortification. I've learnt, though not easily, to walk in them on the rubble, but here it was even worse. Permanently distorted legs hurt unbearably. Gases emitted by burning sewage in the bottom made a head spinning, which was an unbearable burden. We arranged stops more and more often, there are more and more of the resigned, sitting down in the flowing waste. I have an irresistible desire to lay myself down and stand up no more. It's only the awareness that everybody would walk over me which prevent me from this.

It was about halfway when Wojtek's helmet has fallen down into the sewage. The guy, having been on the verge of his endurance, put it on his head thoughtlessly, not having poured out its contents. It was just then when he's realized. Words, which reached us, are not made to be repeated. Everybody's laughing. We can't control ourselves even though it makes Wojtek more nervous. However, it was probably the reason why we move forward more easily.

After a while (it's not easy to precise something so abstract in our situation), sewage tunnel gets even lower. We bend our exhausted back even more. Ankles, spine, everything, the whole body is getting filled up with pain. Finally, we've got the message that there're only 500 meters to the end of our road. How to pass it? Finally, there are 200 meters, and then 100. Those last 100 were probably the longest 100 I'd ever passed in my entire life. The pain, exhaustion turns into a kind of an endless stupor. In spite of it, we're speeding up - just to get faster, just to get to the light.

We're leaving, no - we are rather pulled out by some anonymous hands. We confide them our stinking, profaned bodies. We're not able to do anything, no feelings strike us. Houses, undamaged, unharmed are emerging from the dusk. It's impossible to believe.

We're on Warecka street, the corner of Nowy Swiat street. We're being led for the supper. Light. There's even water, it's clean everywhere. Each of us ate one plate of a lentil and went to bed. We're falling on the straw on the concrete floor as sacks stuffed to the top. We fell asleep right away. None of us smells fetid reeks.

And the hungry days in Srodmiescie began.

And there were rumors going around that "Starowka" is "looting". And they don't give the food. Each theft is added to our account.

For us, who have left the rubble of Starowka, where sometimes one, the only one wall would hide our presence before the eyes of the enemy, hard times have ushered in. The quarters on Kopernika Street at the cinema "Cassino", two hungry days and nights spent on the chairs. From there the transfer to the hotel "Savoy". We're moving out in haste- everything's burning - fortunately, there are no casualties. The next quarters are the conservatory. Something's calling inside me - "don't go, don't go". What does it mean - the order will always remain the order.

From that place I went to drop in on Ms. Halina (the sister of the commandant), on Kopernika street under the number of 13'th. She was residing on the second floor. She maintained a good order. What books! It's hard to go away. Planes. Bombs falling on our house. Everything's shaking. There's a hateful smell of a plaster again - an omen of misfortune.

Stukas during the air-raid in Srodmiescie (photo Sylwester Braun)

I go out to the hall. The first bomb. The second one. Doors are collapsing, stairs, how am I supposed to know what's collapsing, there's absolute darkness, dense dust-storm, there's nothing to breath with, I'm lying, I'm afraid to move. And it all took fractions of the seconds. I can see nothing. In every moment I might fall down with the running rubble, from the second floor. I'm waiting. It's brightening up. The third and the fourth floor collapsed, two people are buried alive, I hear voices of rescuers. Ms. Halina is unharmed. I know nothing any more. I've come to myself not until I was on the ground floor. I was lying on the bed of a great Dane, waiting for the doctor. He's standing above me and looking at me with his sad eyes as if he understood everything. I was afraid of the handicap. What will happen now? I'm distastefully dirty. I'm going on though everything in me is screaming: don't go, don't go! They lay me down on the next bed. I'm lying in pain, filthy. It has already passed 12 hours from the bombardment. We've installed ourselves in the corner room from the garden side. Windows are very low. Hand grenades explode in the garden- the panes are falling down. As if they followed our trace. There are planes arriving. There are bombs, only two. One of them is a demolishing bomb, the second one- incendiary. The walls are falling down. We are in flames. We're running. Janka and Bogut didn't want to go downstairs with us. They got covered. They call for help. Everything's burning. We can't reach them. They are calling more loudly, more desperately. Wojtek can't stand a tension. He wants to shoot himself. We're getting away. They are still calling. They still have guns. They're not going to get burned alive?

We don't know where Ms Janina is. Some of the girls got lost somewhere. We've got to the Kazimierzowscy's Gardens. A hand grenade welcomes us. Our people, invisible, shout from the hiding to withdraw. We're heading for Okolnik street- there are maundered soldiers. We can't believe what we see. A man is hanging the white flag.

- What are you doing, what do you think you're doing? - he doesn't respond.

There are shots. He curled up. The white flag on a stick folded up. They've killed him. Which one of our people?

Some troop armed to the teeth leaves the outpost. Our boys want to take the gun away from them.

- I'll shoot, I'll shoot! - scream a boy who's barely grown out from his childhood and is aiming at us with a barrel of the tommy gun. We're infuriated to the extremes, wild, bloodshot eyes. He's bound to carry out his threat. No wonder - he was growing up during the times when one would pay the highest price for the weapon. The situation becomes dangerous. Finally, after some time of the tension the common sense comes to us. We're going away. Insurgents, having been attacked by us, follow us with their eyes, standing on their positions. Maybe they've realized what they had wanted to do? Maybe they've realized that they would have deprived another troop of the rearguard.

We're going among houses in flames. Everywhere is the rubble and destruction, but it doesn't impress us any longer for it's our daily scenery. We are impressed by the whole houses, streets without debris. We're getting closer to Chmielna street - a lost army. We are totally confused. Our commandant is still absent. We're reaching Wspolna 7 street by some corridors, underground passages. The quarter is supposed to be prepared here. Nobody knows anything. They welcomed us without an explanation.

The last days on the Starowka went without the press, without the messages behind our own fortification. On the following day, in Srodmiescie, I met Halinka Adamowiczowna and the news from the world has showered.

Barbara Bobrownicka with her colleagues from the one hundred and first company of the "Boncza" battalion. The photograph taken by Sylwester Braun on the back of the Poczta Glówna (Main Post).

I got to know from the very beginning that we've been finally acknowledged as combatants. What does it mean? After a month of the fight? Who have we been to them so far? Only the rebels, or more simply: bandits? So there was somebody who for the whole month was haggling over us. What price did he have to pay, what effort did he have to put to save our survivors from the scaffold? Yet, they've included us into the shelter of the Geneva Convention. How many doubts they had- oh my stupid mind. I haven't got to know yet if Marysia (sister), who was killed with Irka Czachowska, as a nurse in our troop, who would take care of every harmed sparrow, would become a "bandit". Do we have a backward right to include our fallen into our ranks? I'm an ordinary soldier, maybe even too ordinary and for that reason, everything I do is plain and clear for me and this is probably why I don't get anything.

In the meantime Geneva Convention protects the German soldiers. It's not the end of the bad news. It is probably in abundance. There is almost no food, the English lie to their citizens that they give us aid. Telegrams from "Bor:" (gen. Bor-Komorowski - commander of Home Army) to London remain without an answer.

Russians won't come until our authorities are there, for they don't want to act as usurpers. Editorial office creates favorable news to keep spirits up. They've already started to negotiate with Germans who have, so far, laid down the unacceptable conditions.

Civilian population is to leave the city. Out troops are to be taken captive. Who will believe them? The telegrams from London influence the postponement of the decision. A thousand of bombers will come with an aid. Germans are insisting on us. There are bad weather conditions. There are no Allies. They wait for the better weather, we wait for them - they are bound to arrive.

The representative of the ZSRR (Soviet Union) persuades us to hold on. There's no aid. There is still the lack of the full membership on the conferences on the highest level, required to decide (one time it's for the member of the Government, the other for the one from Rada Jedności (Council of Unity). It's dragging away. People are dying.

Finally, Germans have left us two hours to decide. 50 of Stukas (German bombers) wait on the call. And then- an unbelievable thing- a droning of soviet planes under Warsaw. We have the defense. Stukas didn't take off. No decision was made. We keep on fighting.

We'd rather not know it. There is even no-one to share it with. We're not allowed, we - ordinary soldiers, to take away illusions. And out there from Powisle district sounds of the fight, there are our boys. And they again, without rest- poor guys - Germans took over Powisle...

My knee gets even worse, I can't walk even if it has a stiffened dressing, and temperature is of almost 39 degrees celsius. I go to the other side of Aleje Jerozolimskie street to aunt Muszka Koszarska. I have to get a bit of treatment. I enter her house- it's really hard to believe - polished floors, cleaned windows, everything's in order. We're eating a delicious meal - puree made of peas with garlic and salted butter. What a delicacy. Despite the fact that we eat the same dish three times a day, one can't get sick of it. I feel very well here and I'm starting to be afraid if I'm not going to get out of the habit of being at war. I have to run away from that place for I'll fall apart. But just here I was meant to experience one of the greatest days during the Uprising. Even, regular droning was slowly coming closer. Sky was moaning from the rattle of engines. My God, how many of them? How many bombs for the only one Warsaw? They are flying in the even line. Suddenly, somebody shouted, all the people are screaming: these are our people, anti-raids cannons rush into our joy. In answer, the sky starts to bloom; it's for the colorful parachutes. How ridiculous German defense seems to be, in the view of such a power, up there, in the view of its undisturbed peace. Not even one wing of the plane budged. They are so different from those of the German, which in satanic skids, diving and hisses aim at us with the worst they have.

People are screaming: - It's landing, it's our people! They are falling into each other's arms, crying...Voice of a woman towers above the common joy: It's my son, my son! First ripped parachutes fold up painfully. Despair...

It's not people, there are pods with the weapon- an anonymous voice comforts us. The wind was carrying away pods in the direction of Wola district. 30 % of the drop landed on the German territory.

They didn't forget about us, didn't forget- people repeat over and over again.

How much we felt lonely, how much we needed this gesture of the memory. They took off. And yet maybe not entirely. They disappeared somewhere behind the horizon, mutilated by stumps of the collapsed houses.

I'm struggling for a pass to be back in my troop. They don't want to give it to me. Why? Fortunately, I met Halinka Adamowiczowa again and she's fixed everything right away. I'm coming back. This is a kind of escape from me, from the fear that this silence and comfort will make me fall apart. Yet, a human being creates himself and doesn't want to disappoint himself.

My leg is still in an elastic bandage, but it's already working. The way leads through the underground tunnels, basements and holes pierced in them. Corridors in the basements are signed, they lead in many directions. There are a lot of people everywhere who willingly inform you. Here I meet again with the life of the civilian population of Warsaw. They are sitting hungry, miserable, dirty, worn out, even living, and existing under the ground. Common misery not only brings people together but also divides them. There's no way not to perceive it, though I don't have much time for chats, but they still expect from me some news, comfort - it's all because of this armband. I have to take a rest from time to time - my leg hasn't got used to walk yet. And this is when they talk, complain, irritate, accuse, ask when it's finally the end. As if the fact that I'm a soldier would make me an omnibus. I try to keep their spirits up. I immerse in their despair and feel as a liar. They know nothing about it, they cling to every brighter word and I have to force myself to say it.

However, there are more and more of those who look at us unfavorably, words of reproach get tough, accusations more difficult to confute. The biggest bitterness accumulates during the queue for the water, where the fact of standing for several hours, sometimes under the fire, was a real ordeal for the impoverished population. And out there, inside the distant, unknown basements, lived our families. Were they alive? One can't allow oneself to have such thoughts.

This is the way civilian population lived, died and was born. A despair, what did they eat? More and more people wanted to get out of the underground. Germans assigned exit hours for the civilians.

Finally, there's a passage through the ditch on Aleje Jerozolimskie street. (How many people died during digging it). There is a long queue of men carrying sacks with wheat on their back. Bent back. Unseen faces. I joined the stream of the walking people. More or less in the middle of the way he turned back and looked at me. With the infuriated face.

- It's all because of you - he put his sack and started to walk in my direction.

A terrifying fear. What does he want to do? The others also put their bags on the ground, the queue was stopped. The atmosphere became unusual. I clung to a steep wall. How small I felt then and he was walking towards me. The others also did, though I'm not sure of it. The horror took my consciousness away. I only felt that in a moment something terrible would happen. And in this moment a peaceful, male voice started to speak:

- People, what did this girl do to you?

Faces were turning away from me. Legs started to move. Sacks on the back were getting farther in a long line. I was standing a long time clung to the uneven wall until my legs brought me the long line of people moving on with the bags on their back.

So I found myself on the other side of Aleje Jerozolinskie street among our boys and the commandant.

I felt right away that something's changed. Unfinished sentences, evading glances... Finally, there's a conversation with Wicek (Rankowski) and Wojtek (Wronski). "Because Baska, you don't know that this "Szczerba" is different "Szczerba" from the Starowka..."

Not the same?...

He didn't go to the post even once (then our military points were settled in the ruined main post). Something's gone down. The commandants don't have the right to be depressed. It was only then when I realized how important a commandant was to his soldier. And our "Szczerba" is not an ordinary man, not an ordinary soldier. Words of grief. How they are looking, how they look at him. How great part of us resembles little children who still need support.

I can't believe it myself. I feel if something's falling down again. For out there, on the Starowka, where everything was lost, nothing could sap our trust in "Szczerba". For it was his balance, peace, his command kept this vital distance in our hands, honestly speaking - despite any reason. (It was only in the sewage drains when he admitted that he hadn't believed that we would have kept our positions. However, we had believed and it was because of him).

I can't listen to the accusations, I feel that they hurt him, can't defend him. And the boys, they have also changed. I'm looking at harmed, wounded, convalescents and in the inside I'm building up myself against the loss of faith... "Szczerba" welcomes me with joy. I get to know his wife. She's very nice and gay - we grew fond of each other.