The Witnesses' Uprising Reports

Uprising Memoirs of Henryka Zarzycka-Dziakowska

Henryka Zarzycka-Dziakowska,,

born on November 10, 1927 in Warsaw

the Home Army (AK) soldier a.k.a. "Władka"

the messenger and nurse of the AK battalion "Parasol"

seriously wounded on August 28,1944 in the Długa str.

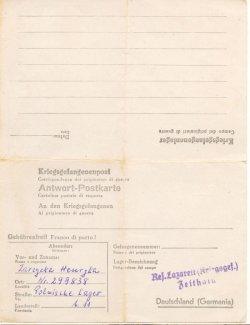

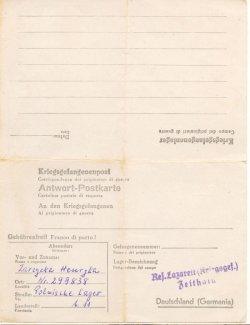

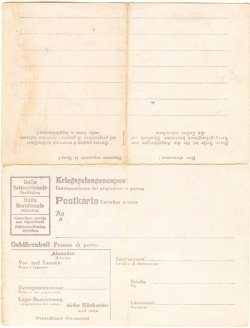

POW hospital Stalag IVB Zeithein

Captive no. 299838

What happened later on

Having left the sewer in the Warecka str. I was just delighted by what I saw -freedom, Poland exists! The sun shining above my head, people wearing casual clothes, window panes in places they should be. I was lucky - seriously wounded were not allowed to enter the sewers, just those who were able to walk could go in. Just few were being carried, commanders at the most. Other wounded people had been left in basements or hospitals . Germans shot most of them. I was lucky.

I remember being taken out from the sewer by two muscular girls. They cleaned me, gave me coffee and sandwiches.

Despite horrible pain coming from my wounded arm put to my body by means of bandages, I didn't want to go to the hospital at once. The boy who was looking after me, was urging me to do it. However, firstly I wanted to see Mum. I managed to make him give me a refferal and promised solemnly to go there soon. And I went towards the Boduena str. Mum burst into tears, having seen me, although I looked horrible. Together with neighbours she took off my stinky camouflage dress, then lay me on the table and washed me neatly. My clothes covered with sewers' waste and my shoes were burned in the incinerator. I put on some dress. And I went to the hospital in the Śniadeckich 17 str. (the building escaped destruction during the Uprising).

In the hospital I stayed until the end of the Uprising. A vast wound of my shoulder (at least 15-centimeter-long, with a vast loss of muscle tissue) was healing badly. Also wounds of shrapnels in my leg troubled me. When the Uprising was coming to an end, my parents wanted to take me from the hospital but its commander didn't allow them. After the capitulation my parents left Warsaw together with the civilians and I was taken to the POW camp together with other wounded ones.

On October 7, 1944, after the capitulation, Germans provided trucks to the hospital and drove us to the side track by the Central Warsaw railway station. There the wounded and medical staff were loaded to cattle-trucks. We were given food but there were no bandages. German wearing white doctor's gowns behaved properly. An old German reservist handing a rifle was keeping a close eye on us. On each stop he used to leave this rifle under our protection while going for food for us. It occured that sometimes he came back from these outings beaten by Gestapo agents and then we used to dress his wounds. Pus was raging inside my body, my arm was inert, I suffered from high temperature. It was a phantom-train. We were nowhere welcomed. We left Warsaw in the evening. The whole night we were being driven at enormous speed. I heard explosions of grenades hitting the train, maybe someone was trying to rescue us. In the morning we were on the German land. I remember Głogów, our stop place. Local inhabitants were looking at us disgusted and were pitting at us. I don't remember the name of our destination but our transport was taken to Stalag IVB Zeithein.

It proved to be an international camp and hospital. Captives of different nationalities were staying there, excluding Englishmen and Americans. After our arrival it turned out that there was no place for us. Nobody even started to unload us from the trucks. A German officer told us using broken Polish that negotiations were being conducted with Italians who were to give up some of their lodgings for us. If so, they would have to clench themselves, which meant two persons sleeping in a place for one. The officer stated that if Italians did not agree, we would be sent to Oświęcim. There everybody was welcomed.

Italians gave up a half of their barracks for us. The wounded started to be unloaded from the train. Italian captives took carts from German peasants and started to put there people who had been taken from the train. We were looked after heartily. While it was true that plank beds were bugged, we had place to sleep. People who used to sleep in those places helped us as much as they could and brought us bedpans. When the first days passed by, they started to visit us socially, player for us and sang beautiful Italian melodies.

Polish captive doctor and nurses were doing everything they could to help the wounded. It was not so easy as Germans were not particularly interested in saving wounded insurgents' lives. My wound was healing badly. I owe a lot to one of the nurses, who looked after me cordially. She used to often come to me after the curfew and massaged my arm in order to animate it. As a consequence, the arm survived. Despite a vast scar that goes along the whole shoulder, the nerves function and my arm is not inert.

On October 13, 1944 I met uncle Tolek. Firstly, on a cart, I saw a protruding leg in a plaster and then a Saw a well known face. I started to shout, "Tolek, Tolek". He heard me and said, turning his head, "Don't worry, I will find you." Since then we had been staying together. Despite being really hurt, he helped me a lot.

There I got to know about the death of "Ziutek", I didn't believe it - It's not true! But I became certain it was so for sure. "Bronek" confirmed this - he had been by our friend's dying. "Waligóra", with whom I participated in so many action in the Old Town, them stayed in a field hospital (in the basement) - I met her again in Zeithein.

After two weeks my brother Marian was brought there. To his mind, he would not survive there and, as a healthy man, he reported himself to another camp, 12 kilometers away from there, the one in Muhlberg. Few boys from "Parasol" did the same. In Zeithein there were seven of us from "Parasol" (two girls - "Waligóra" and me and five boys). In the case of deconspiration they were threatened with danger due to their activity in the occupation times (including executing death sentences on the Germans who were convicted by underground courts). Two or three of them also relocated to another camps at the earliest convenience. My parting with Marian turned out to last a very long time. We met not until 23 years later in Australia, where he emigrated after the end of the war in 1945.

As for food, it was very difficult to gain. Not earlier than for Christmas we got packets from the Red Cross. One had to survive from October till the end of December. Whoever managed, felt better in the future. Then trade started between either captives themselves or captives and Germans. I didn't smoke so I had valuable foods for exchange.

a form of camp correspondence

Most people staying in the camp were Soviet captives. When Germans had been informed about the plan of shortly takeover of the camp, our colonel was given command by a German camp commander. The colonel, subsequently, gave i tup for Russian officer, not to expose himself to the captives. Just before the takeover SS men came and beat the new commanders cruelly.

In the middle of April 1945 the Soviets and Cossacks liberated the camp. They got into the camp on small carts pulled by small horses, looking like ponys. Liberated captives started to wonder what to do next. My uncle, who dealt with "Cichociemni" (soldiers trained in the West and parachuted over Nazi-occupied Poland to join the resistance forces) during the occupation and was afraid of any contact with NKWD decided to move West. He organized a group of officers and their wives and together they planned to free themselves from the Soviet guardianship. He wanted me to join this group, too. I started to shout that I disagreed that my parents were alive and I had to come back to Mum. If I came back, she would stay alive, if not, I would lose my mother.

After short consideration uncle said, "Your brother left you but I will not leave you." And he organized a group to come back to Poland. There were eight of us: Uncle, me and six boys. The truth is, I was also in boy's disguise - my hair was cut short and I was wearing an English uniform (which I got from the Red Cross), just like the others. With Uprising armbands on the uniforms, we set off on foot.

Having covered a distance of about 10 kilometers, we reached the crossroads, where we noticed a pile of bicycles, both male and female ones, lying by the road. Few Russian soldiers, probably non-commissioned officers, were keeping eyes on them. Having seen us -wearing English uniforms with armbands on - they called us. The boys started to talk with them. The Russians told us to take the armbands off as our next meeting with NKWD may end badly for us. So the boys digged the armbands in the soil. I hid mine in the uniform jacket's pocket.

The soldiers said, "Take the bicycles." Without waiting for subsequent encouragements, each of us chose one bike and we set off. We rode the bicycles over 100 kilometers I was pedalling with one hand on the handlebars. The second, wounded arm, was put in a sling. During that time we were sleeping wherever it was possible, mainly in deserted houses or barns. There was not much to eat. I remember that once we managed to shoot and eat a goat. Consequently, some boys got ill due to bad food. I didn't feel hunger, my wound would still make my suffer. As I was eating little, gastric problems omitted me.

At last, in Leszno, we got on a train. Then I fell ill, too. Pus was leaking from my wounded hand; there were no bandages. We advanced to Włochy near Warsaw where our friend lived. His father was a writer. I was put in a bed while uncle Tolek set off to Warsaw in search of my parents. And he succeeded. Meeting both of them was moving.

We tried to start leading a normal life. My father was employed in the Lower House of Parliament and there in the hotel we were given a small room. I took up education that had been interrupted during the Uprising. In the Górnośląska str. there was the school complex where many young people like me could prepare to take a Matura exam.

These were peculiar times. As I had nothing more than my English uniform which I had come back from the camp in, I was wearing it for 2-3 months. One day a NKWD patrol started to chase me. I was escaping along the Wiejska str. and rushed into our flat. I managed to run into an elevator and press a button before I could be caught by the Russians. If they had caught me, I would have been in great troubles. Many Home Army soldiers, having been captured, were being driven to the camp in Rembertów and then sent to Siberian camps. Significant number of the people were never to come back.

Mum, having heard about that incident, took my uniform and went to the market place in Rembertów, the place known of selling clothes. She sold the English uniform and bought me some women's clothes: a dress and a blouse. Since then I hadn't looked like a soldier anymore.

I decided to continua my education. After passing the Matura exam, I took up a job in the main Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Firstly I had been wondering about SGPiS (the Warsaw School of Economics) but finally I took up studies at the Warsaw University in the department of law. I hadn't informed about my membership of the Home Army. I became a student. When the time of the first examination session was close, the Law Faculty dean got to know about my being a Home Army member. One day he simply started to chase me along the corridor with the intention to take my university credit book by force. In front of the building there stood a car into which he wanted to put me and bring - supposedly - to NKWD or UBP (the Committee for State Security). While running away, I stumbled myself and hurt my knee. The wounded leg started bleeding. People gathered immediately. Apparently there were many former Home Army soldiers at the university because the over-zelaous dean became quickly surrounded by young people, who kept asking, "What do you want from this student?" The frightened "scientist" freed himself, got into the car and drove away.

I remember my running home, terrified. I was going along the following streets: Krakowskie Przedmieście, Nowy Świat to Wiejska. My father got much irritated. He knew several professors from the Warsaw University, including prof. Kalinowski and prof. Rozmaryn. They promised to help me. During the next three months I passed the examinations of the whole academic year. Afterwards, prof. Kalinowski said, "Since you have all these examinations passed and marks put in your credit book, show it to the dean now." I did so. The dean, whose name I will not reveal, looked at me as if I was some phantom and then I was not persecuted by him anymore.

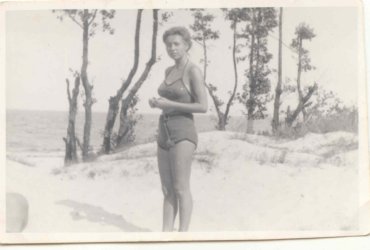

Westerplatte in the year 1948

Later on I took the barrister application. The then dean, whose name I will also disregard, knew my father and helped me to join the barrister's group. After a year of my application, that man got to know about my past. He rushed into my workplace and gave me a slating cruelly. He was grudge against the former Home Army soldier who dared to study in order to become a barrister.

lawyers' training in the year 1955

Repeatedly afterwards I experienced different forms of humiliation because of my biography. I was no exception in that matter. There was such a fate of thousands of my friends. This was how the people's government used to repay us for hardship and blood shed in the fight for the independence of Poland. Nevertheless, I reached the end of the road. Thanks to my own stubbornness and help of friendly people, whom I have always had nearby, I became a barrister. This had been my profession for 48 years (till I was 75). Then I started to suffer from some health problems and since the year 2002 I have been a pensioner.

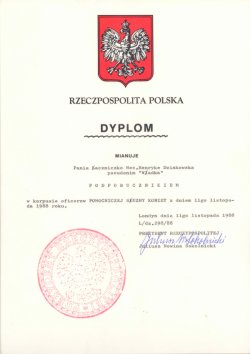

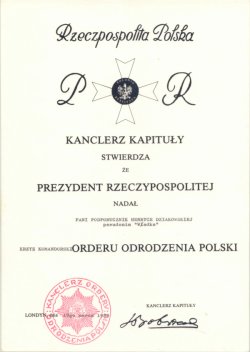

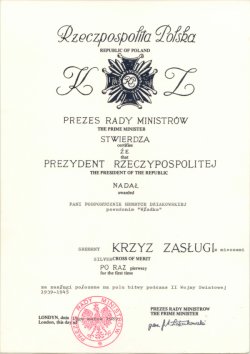

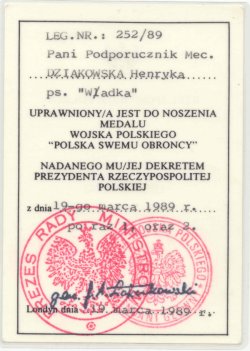

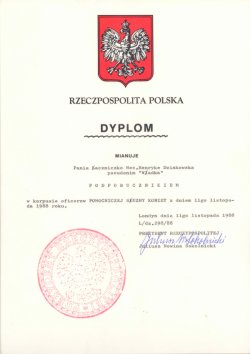

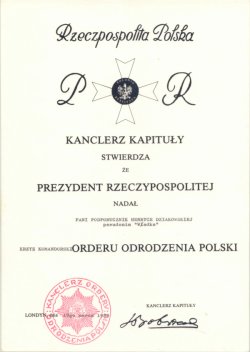

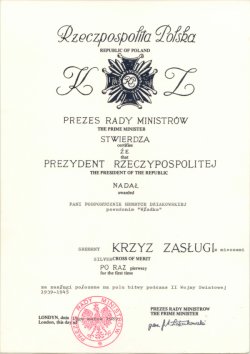

Lack of esteem from the communist government was compensated by the signs of respect of the Polish government in exile. In the year 1988 I was nominated to the rank of second lieutenant and in next years - rewarded many orders: Commander's Cross Polonia Restituta and Silver Cross of Merit with Swords

second lieutenant's certificate

certificates: Commander's Cross Polonia Restituta and Silver Cross of Merit with Swords

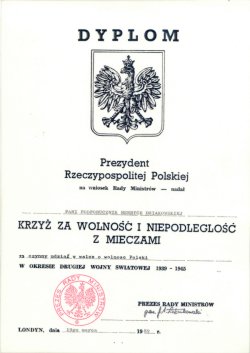

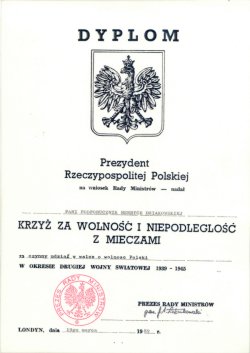

Cross of Freedom and Independence with Swords and Medal of Army.

certificates: Cross of Freedom and Independence with Swords and Medal of Army

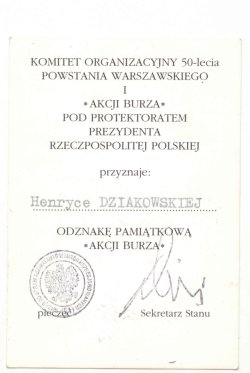

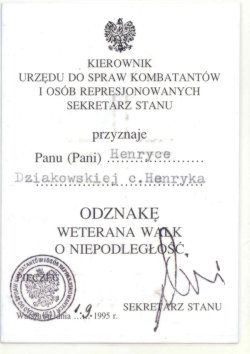

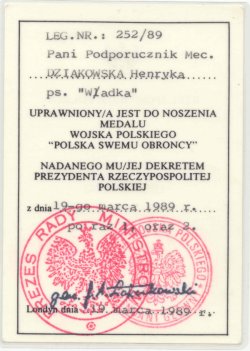

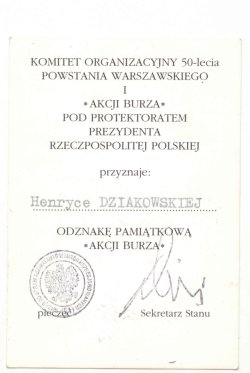

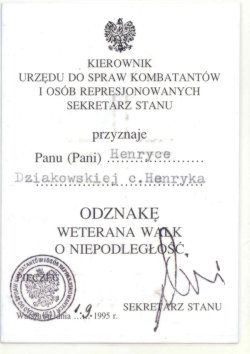

I also possess the "Storm" Operation medal and the Veteran of Fights for Independence medal,

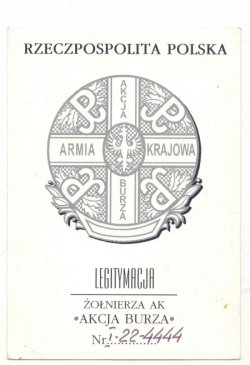

"Storm" Operation medal and Veteran of Fights for Independence medal

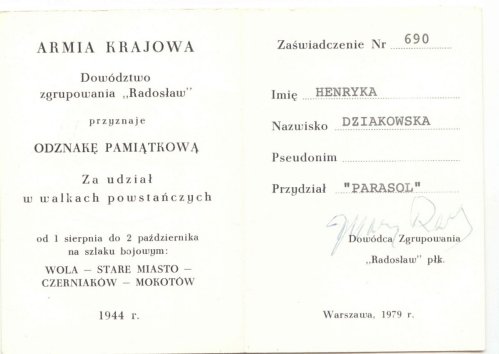

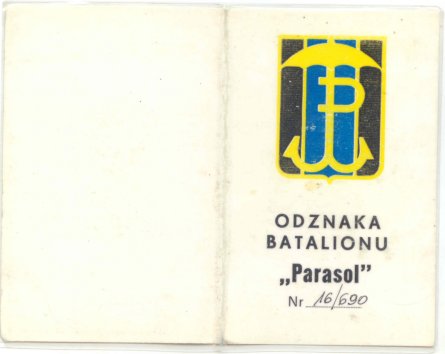

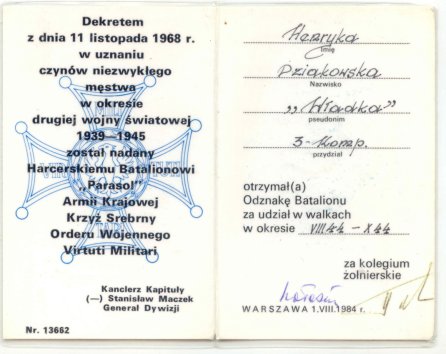

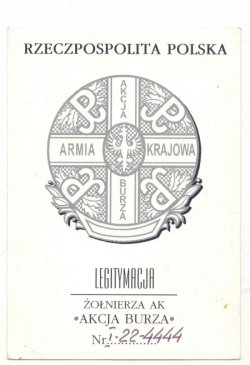

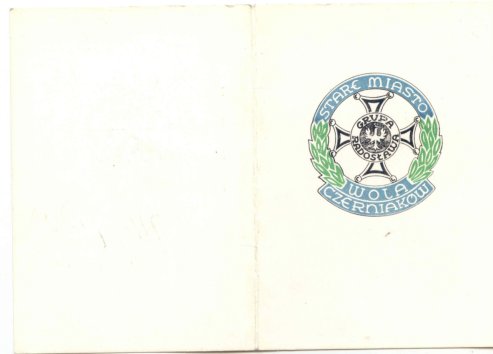

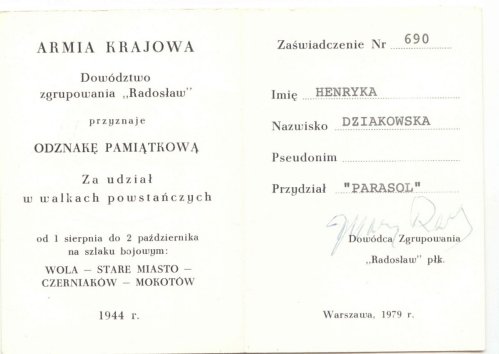

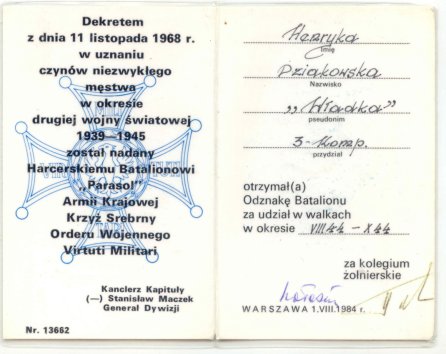

the "Radosław" Unit medal and "Parasol" Battalion medal.

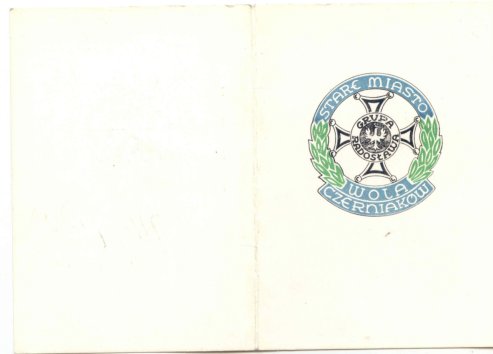

"Radosław" Unit card

"Parasol" Battalion card

What I consider truly moving for me is the fact of awarding me the medal for courage and sacrifice Digno Laude (which means the one who is praiseworthy) which was given me by the Warsaw Medical Association.

Digno Laude medal

My fate is similar to experience of hundreds, maybe even thousands of young girls who once made a decision to take an active part in the history of the Polish nation during the six dark years of the occupation 1939-1945.

Henryka Zarzycka-Dziakowska

|

Henryka Zarzycka-Dziakowska,,

born on November 10, 1927 in Warsaw

the Home Army (AK) soldier a.k.a. "Władka"

the messenger and nurse of the AK battalion "Parasol"

seriously wounded on August 28,1944 in the Długa str.

POW hospital Stalag IVB Zeithein

Captive no. 299838

|

edited by: Maciej Janaszek-Seydlitz

translated by: Monika Ałasa

Copyright © 2015 Maciej Janaszek-Seydlitz. All rights reserved.