Zbigniew Galperyn,

born: 1929.05.18, Warsaw

rifleman, a soldier of Armia Krajowa (Home Army)

a.k.a. "Antek"

battalion "Chrobry I"

First-hand accounts of the Warsaw Uprising

War reminiscences of Zbigniew Galperyn - a soldier from "Chrobry I" Battalion

Uprising

|

|

The first attempted assembly took place in a church during a morning mass. It was the first time we saw our platoon - thirty-something people, in most cases young boys attending the mass. For the first time we saw each other in such number in one place. Until then we had only been meeting up to 10 people. We knew each other by sight, but except for the official assemblies we were not allowed to show to show acquaintance even in the street, unless it really was a close friend. The mass ended with the order: "Disperse!"

The second assembly was scheduled on the 1st at 3 p.m. in Wola District, in Grzybowska Street in the area of Wronia Street, which was perpendicular to the former one. We were to report to a private flat in one of the houses. It has to be mentioned here that almost every one of us was from other district than Wola. From our ten two did not come. As it turned out later, one of them had been wounded in Srodmiescie District on his way to the assembly point and had landed up in hospital. The other one was the only one from our group that was lived in Wola District.

The others arrived at the assembly point at 3 p.m. Until 4 p.m. we were given armbands, which we put on our left arms. We were given grenades, side arms, several rifles and then we were waiting. We were waiting for an order telling us what to do next. It is going on for 5 o`clock, we hear gunshots and receive the order.

Two companions are going to guard a gate; there are many young boys in the house and if the Germans came, they would get everyone. Traffic in the city dies away and this is how our first day of the Uprising begins.

Around 6 p.m. a small 6-person group goes for a patrol. We take grenades, one rifle and we leave. We walk round the square of streets to learn about what is going on in the nearby streets. We meet other insurgents with armbands and people hiding in gateways. Every once in a while we hear gunshots from nowhere. As I learned later, the objective of our battalion was then the reconnaissance of the closest vicinity.

We are going further and I see the first killed German, without a helmet. He is dragged by a boy with a rifle, not much older than us. An ordinary German, wearing military boots and uniform, must have come here accidentally. The boy is dragging him, and the head of the killed one is bouncing on the pavement. We stop and watch the situation. All of a sudden, and to my surprise, I see another boy, not from our group, running up to the killed German and kicking him in anger.

I look at this dumbfounded. What he is doing this for, when the German is already dead, is already eliminated, and this is unnecessary. It was my first thought. It did have an impact on all of us.

After the return from the patrol I received the order to go to Wronia Street and check why the second one from our ten had not come. I entered a private flat and found a woman with two young children. I asked her about that boy, who had been working somewhere and had not arrived. The mother asked with anger why I was asking about him, with the intention of taking him away. He was needed at home, she was with two young children. I felt very abashed, seeing the reluctance of the woman who I wanted to take the husband or a brother from.

I was a bit surprised at the same time, as there was no such resistance in my home. Maybe it was so, because we had been meeting at my place, my father had been working all the time, but my mother saw my companions, although she had not asked me what we had been doing. When we had been going out with my brother, she had had no reservations about our going out and not knowing when we would come back. When we had gone to the assembly I did not see with my parents anymore. The boy I was sent for arrived to us later. He died in Wola District.

It has started to rain. It is already curfew time, streets has become deserted. It is relatively calm. We come back to "our" flat. A few hours have gone by, we have not eaten any dinner. We go out with a companion to a nearby bakery to get some bread. It was the first time I undersigned the receipt that we confiscate a number of bread loaves for the Home Army, I do not remember how many. In a basket we brought the bread to the house where our group was waiting. This dry bread with tea was our supper that day.

We stayed in the assembly point until the morning. In the night I was on duty or, using lofty language, on stand guard, near the gateway. We were on duty in twos. Of course, the gate was closed. Silence and calm; here and there the whir of a car. Cautiously I opened the gate and looked out on Krochmalna Street. I heard a car somewhere there, but I could not see anything. I moved back to the gate; nothing happened.

In the early morning of the September 2nd we go out in a tight group. Every one of us is wearing the armband, a half or a third of us is carrying a weapon. In general, German stick grenades. A lot of civilians appear in gateways. People are cheering and treating us with cigarettes. I did not smoke, but to refuse the treat was not the right thing to do. Back then cigarettes were handmade, younger readers probably do not remember this. One loaded the cigarette using a special machine: without a mouthpiece - from both sides, with a mouthpiece - from one side. Tobacco was imported from Lubelskie Voivodeship, flavored with various aromas to taste better.

Equipped with the cigarettes we arrived at a school in Krochmalna Street. It is an ordinary school with a large gym. There is a crowd of young people in there. The newcomers volunteer; they are not trained. We are a fixed group, we have our commander, we know each other and we are partly armed.

Suddenly, a young man bursts in. He says that their squad attacked three tanks. One has been destroyed and the other two have been captured. He asks whether there is a mechanic in the room who will help to start up the captured tanks. Our commander is faced with a serious dilemma. As it turns out, he is a mechanic, although we did not know about it. He does not want to leave as, we were with him during all the occupation. He taught us to aim, shoot, he conducted all our training.

But no one answers, so he says that he has to leave us. He will do the job and return to us. Now he must go, he feels obliged to help them in starting the tanks up. We are left alone. He never came back to us, he died there in Wola District. After the war I attended the mass for his intention. He had lived in Aleja 3 Maja in Powisle District. Driving across Poniatowski Bridge in the direction of Praga three large dwelling-houses stand there until today. Our commander lived in one of them.

In the school we received something to eat and then went to the Haberbusch brewery. We found a huge crowd of people there. In this place I have to tell a little about our battalion, its conspiratorial origin and how we got into the Haberbusch building.

It turned out that we were the 4th platoon of the "Chrobry" battalion. There was only "Chrobry" back then, and no "Chrobry I" or "Chrobry II". In the Haberbusch brewery we learned about the conspiratorial history of our battalion. The battalion was a part of the Sub-district I of Armia Krajowa (Area of Srodmiescie - translator's note), and the Region IV in which the commander was "Zagonczyk" (Major Stanisław Steczkowski - translator's note). In 1942 Region IV consisted of "Kilinski" and "Lukasinski" POZ battalions (pl. Polska Organizacja Zbrojna eng. Polish Armed Organization) and the units of lower level - among which there were the "Klima" company commanded by Wladyslaw Zurawski a.k.a. "Klim" and the "Korda" company commanded by Lt Kazimierz Burnos a.k.a. "Cord". These two companies were transformed in 1942 into the "Chrobry" battalion. Billewicz, a.k.a. "Sosna", was assigned as the commander, he was a captain during the occupation, later he got promoted to the rank of major. He was a special cases officer in the staff of the Warsaw POZ and he came with the task of creating the "Chrobry" battalion. In 1943 the "Chrobry" battalion grew to involve two more companies: the first one of "Edward" Kajetanski, one of the later commanders of the "Chrobry" and the second of Marian Wardzynski, a.k.a. "Marian". It was reinforced with three artillery squads of captain "Hak", back then lieutenant, and the battalion was prepared for the Operation "Tempest" (pl. Akcja "Burza", sometimes referred in English as Operation "Storm" - translator's note).

At the beginning of 1944 it consisted of 4 companies:

- 1st company "Edward" (3 platoons),

- 2nd company "Corda" (3 platoons),

- 3rd company "Wiernego" (2 platoons),

- 4th company "Klima" (3 platoons).

As well as of a quartermaster, nurses and messengers.

On the third day of the uprising at the order of major "Zagonczyk" the battalion became a part of the 9th insurgent group formation commanded by captain "Sosna". A WSOP platoon (pl. Warszawska Służba Ochrony Powstania eng. Warsaw Uprising Guard Service) (commander: 2nd lieutenant Franciszek Nowak "Beton") and a half-full platoon of firefighters (commander: 2nd lieutenant Eugeniusz Kohl "Stryj"). The WSOP platoon recruits included also the Navy-Blue Policemen (pl. granatowi policjanci - the popular name of the collaborationist police) garrisoned in the barracks in Ciepla Street, while the half-full platoon comprised of the members of fire brigade of the Haberbusch & Schiele brewery. The squads that made up the 9th insurgent group formation numbered over 600 people.

One of the most serious task of our battalion was to capture Nordwache. There was also a school where military police was garrisoned. Apart from that we had to mop up the Germans from the region that was directly placed under our command. During the first days of the uprising the organization scheme of our battalion had been changed. The division into companies had been given up, and the platoons were placed under the command of captain Gustaw "Sosna" Billewicz. Depending from the needs the platoons could be sent on immediate actions.

As I mentioned before, one of the tasks was to capture the Nordwache. It was not accomplished on the first day, nor on the second. It was not captured till the August 3rd. The best-armed companions from our group took also part in performing that task. They got into the higher floors through a breach from an adjoining house and captured Nordwache from above. I did not take part in that action.

We received the task of patrolling and eliminating the Germans from our region. Snipers posed a serious problem. Often they were Germans that found themselves in our area by accident when the uprising began. In the first days they hided somewhere, but later they, often in twos, found convenient shooting positions. They hunted the insurgents with the armbands from there. When spotted, they fought relentlessly. We were ordered to eliminate those people.

Another task was to protect barricades. The corner of Walicow i Chlodna streets was the first one, and the corner of Krochmalna Street was the other one. There was always someone on the duty on the barricade. I perfectly remember the day when the German tanks were getting closer. The sound of the caterpillar tracks crushing the surface of a roadway. Having had set the sights, we were shooting with rifles to the approaching Germans. We were trying to hit the Germans hiding behind the tanks and shoot into the holes and access doors.

We were lying hidden behind a barricade of flagstones with small lookout holes and we were waiting for their move in order to respond adequately. The result of a rifle's bullet hitting a tank was rather poor. I was often on the watch on the barricade, also at night. The nights then were very dark. Germans were shooting rounds from submachine and heavy machine guns. Some shots in every round could be seen in the dark. One could learn where they are shooting from by attentively listening and watching. Then one would shoot in that place with a rifle. Sometimes it was successful and then the rounds fell silent.

During a daytime we were trying to attack tanks with the bottles filled with petrol. The basements of the adjoining houses were connected with the breaches made in walls. Thanks to that one could move through cellars along the street close to the Germans, close to the tanks. It was also possible to get to the 1st floor, closer to the enemy.

I was on the 1st floor when I saw for the first time a completely unknown weapon. I think it was August 4th or so. Three companions older than me were trying to fire a PIAT. They had some problems with that, because they were not trained to use it. PIAT had a square rest, with the help of which one could wind up the string and then insert a small anti-tank cartridge. One would then base the rest was on the chest, aim in the direction of a tank and shoot. The companions could not wind up the string. One had to lie down on the back with the legs squatted holding the launcher in front. Then one would straighten the legs, winding up the string (it required a lot of strength). The effectiveness of PIAT was not that much higher than our bottles. I saw once that one of the projectiles, which we were trying to spare, did not reach a tank and fell before it.

Neither we could often reach the tanks with our bottles because of the distance. I was one of the better throwers. Thanks to my earlier trainings in dodge-ball game I would throw very far and accurately. Unfortunately our struggle did not fulfill its goals. We did not manage to destroy or capture any tank, but we stopped their attack twice. We would move closer to the advancing enemy through basements and try to hit the vehicles from a ground or 1st floor.

One day when I was on the 1st floor and about to throw a bottle, a tank fired and hit the wall of the adjoining room. All the place filled with red-white, brick dust. For a moment we could not see anything.

From the stay at the Haberbusch & Schiele I remember one thing. In the garages with barred windows in the courtyard the insurgents held German prisoners of war. It was August 4th or 5th . A young boy led a captured German. The event created the double row of interested insurgents that were stationed there. The prisoner walked in the middle. He was a young boy, not much older than me. He wore a brown uniform, with the swastika on the left arm, and a brown helmet. He was really nervous. His lip corners were twitching, the eyes were restless, scared. I did not feel sorry for him, he was a captured enemy. However, I will not forget the face of that young German boy.

I remember also a funny event. An order came to destroy vodka. A boy performing that stood over a sewer, was taking bottles from a box and was smashing them against each other. Vodka was flowing down to the sewer. The crowd of spectators was standing around and watching the "tragedy". The boy took pity over them and all of sudden a bottle slipped away from his hands directly into the crowd. People instantly protected it from destruction.

On August 6th we moved to Ciepla Street to the garrison of the Navy-Blue Police. We could complete our uniforms there. I had all the jacket mauled on a barricade by some shrapnel. I used the parts of a police uniform then. I took a jacket, boots and warm, navy-blue pants. It was a winter clothing and the pants were not comfortable.

From Ciepla Street we moved to the court of justice in Leszno area and there we received camouflage suits. It was everyone's dream. We were uniformed alike, we had police belts from Ciepla Street. Some wore special suspenders to those belts. The belts were handy in carrying grenades. We had several submachine guns gained on the enemy. There was a custom of ripping the decoration of killed Germans off and attaching them on uniform belts or submachine belts. It looked warlike and boosted the morale of the insurgents.

It needs to be said that already at the end of the day August 6th in Wola District we started to experience different reactions of the civilian population who was fleeing from Germans. Some of the Wola citizens were murdered by Germans, others got through with little children to the area held then by the insurgents. Their reactions were completely different from those in the first days of the uprising, when they had been cheering us and treated us with cigarettes. The refugees were even hostile. They asked what had we been doing this for; the Germans destroyed their homes, burned them and demolished. It was our fault that that nightmare lasted so many days and that there was no progress, and the underground army was moving back into the city.

An assembly of better armed soldiers was called and we were told that we would go to Zoliborz District and to Kampinos. In those regions there were the air drops of weapons and ammo of which we had a serious shortage. Later the order was called off and we were informed that we would be going to the Old Town.

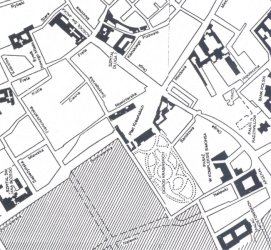

the partial map of the Old Town

On August 7th we arrived at the Warsaw Arsenal where we were given accommodation. For a while we felt like we were on a vacation, it was very peaceful. The Arsenal is a tall, quadrangular building. There were bales of paper put in the windows in order to protect from bullets. In rooms we could get some rest. There was some food was stored up, even sugar.

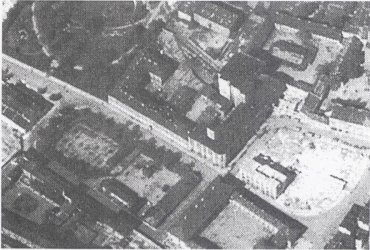

the east wall of the Arsenal from the side of the Nalewki Street

A lot of food was also in the nearby Simons Passage and in the warehouses in Stawki Street, where the supply was coming from. I remember that from those warehouses we received tins with wonderful corned tongues in sauce. We would open the tins with a bayonet. I still remember the taste of those tongues. We were hungry and really sleepy back then.

We were accommodated in the Arsenal, but we were checking what was happening in the Simons Passage, located on the opposite side of Nalewki Street. On the first floors there were offices and in the office drawers we found the second breakfasts of clerks, who did not eat them. Usually it was bread with margarine and hard cheese. The bread was a bit dry, but we had missed it much. We ate those left second breakfast with appetite.

air photograph of the Arsenal and the Simons Passage

The basic meal back then was bailed sago. It was something like artificial groats, transparent balls a little smaller than pearl barley and was eaten without seasoning with grease. In the Simons Passage there was a lot of juices in one-liter bottles, of course, with additives, dyed. There were orange, cherry, raspberry flavors and with that juice one would sprinkle sago. It was awful. We definitely preferred that dry bread. And those unforgettable corned tongues, of course.

From the Arsenal the patrols were being sent to the ghetto, to the Mostowski Palace, to the White Manor situated directly in front of the Arsenal. We were checking that area systematically. During the days of the uprising the Arsenal looked a little different than today. From the side of Nalewki Street it had arcade galleries from the outside and also from the inside on the three sides and their arches on colonettes.

the courtyard of the Arsenal in 1938

In the Arsenal from the side of the ghetto there was a lookout point. The ghetto was pretty far, the sight of a rifle was set at 400m. The observation was performed through a window cover with the bales of paper. Next to the rifle the clips with bullets were lying - 5 bullets in every clip. When I was on the watch for the first time, the ones who had been performing this task warned me: "Listen, you have to make long intervals. We are constantly being watched by snipers, who only wait and observe where the shot came from. They can shoot a lookout directly in the forehead." I treated it very seriously. I had been trained to listen the orders and advices of experienced soldiers.

The rifle in the lookout point was getting jammed. It had a bulged magazine tube and, after a shot, it did not always remove a spent case. There was a cleaning rod next to it, with the help of which one could push out the case if the rifle got jammed. The bullet clips were also at hand. One would observe attentively what was happening in the ruins of the ghetto, 400 meters away. If one saw any movement of Germans, he made a sighting shot, giving them a sign that we are watching. Thanks to that the Germans could not go too far.

When my watch was about to end, a boy came to replace me. He was a little older than me, dark-haired, with a moustache. Being very self-confident, he did not listen to the warnings which I passed him. At the same day in the evening I hid under arcades, as the Arsenal was under fire of Germans. The bodies of several killed men were lying by the wall. I saw that boy from the lookout point among them. In the middle of the forehead he had a bullet hole. I felt very sorry; to some extent I felt guilty for I did not force him to listen carefully the warnings of snipers. He neglected it, having thought he could shoot the Germans with impunity.

The Arsenal was under the constant fire of German artillery, mortars and machine guns. Mortars were the worst, one could not hear a projectile and did not know where it would hit. The sound of the flying wardrobe could be heard. One could hide in a safe place, where reinforced doors or heavy walls protected him. Artillery projectiles and aerial bombs were also dangerous. When an attacking enemy is shooting with submachine guns, one almost sees it and it is possible to hide from it. It is different with bombardments.

On August 21th we had to leave the Arsenal. There was a heavy artillery shelling all the time, and a Goliath tracked mine destroyed one of the corners. The Germans were literally on the one side of the inside arcades and we were on the opposite side, shooting to each other. They had a lot of machine guns which gave them a great advantage in comparison to our rifles that had to be reloaded after every shot. They were not even submachine guns. During the fight inside the Arsenal we heard German orders, the shouts of the attacking soldiers nearby.

We had to retreat from the Arsenal. We moved to the Simons Passage on the opposite side of Nalewki Street. The side of Dluga Street and the Arsenal were dominated by the Germans. The intensive bombardments began. Before a bombardment the Germans would move back and then come back to their positions again.

Simons Passage before the break of war

In the meantime, on August 20th there was another assembly and we were told that we would fight our way through to Zoliborz District and go to Kampinos in order to replenish weapons and ammo. For the second time the idea was not realized.

In Simons Passage we had a moment of rest directly after taking a position. It was not a planned rest. It was not like that in the Old Town that we fought during days and rested at night. It was a pot luck, or rather it depended upon the higher or lower activity of the enemy.

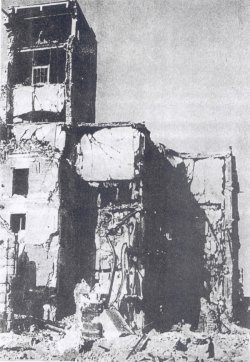

Simons Passage from the side of Nalewki and Wyjazd Streets. The façade demolished by a "Goliath"

During the one of free moments boys organized something like a cabaret. One of them, wearing a police uniform from Ciepła Street told a joke that I still remember. He was talking with the Silesian dialect, he was from Silesia. The joke runs as follows: "In Silesia there is a custom before Christmas to hang hares outside the windows. Two slyboots were walking down the street. They saw a hanged hare and one said to the other that they could take it down. He told him to stand guard and he would do it. He climbed a gutter and he was already holding the hare, when a policeman came. He asked them what they were doing. The one on the ground answered that they had bet that the other one would climb a gutter and on the quiet hang the hare before the window of his mother-in-law. The indignant policeman said that those were silly jokes and told them to take the hare and go away. So did they."

I remember also another joke. One of the officers told me it when we still stationed in the Arsenal. "What is the difference between a stallion and a mare? - A mare has the tail one hole above". Back then those jokes did not make me laugh, but I find both engraved on my memory.

On August 24th the Germans attacked the Simons Passage from the side of Dluga and Wjazd Streets. The latter one, which curved to the Simons Passage, does not exist any longer. We occupied the basements of the Passage. The Germans were scared to enter them. They killed the insurgents on the ground floor and threw grenades below. We were resting when they commenced attack.

Simons Passage from the side of the Bielanska and Dluga junction. On the right - corner house by Dluga Street

We jumped off the wall and waited for the enemy. They were shooting continuously with their submachine guns, throwing grenades, but were scared to go underground. From the basements located farther an order came to move back deeper into the Passage. I left my helmet, which was lying on a bed in the quarter, and started retreating together with others with my head uncovered. The constant shooting with submachine guns could be heard all around us from the side of Nalewki and Wjazd streets.

A person running next to me fell down, his helmet fell down of his head and rolled around and went under my legs. Unfortunately I knocked against it and in that very moment I felt heat in both legs, in thighs. Apparently I got hit by a submachine gun burst.

I fell down to the ground in front of me. I lifted myself up on my elbows and realized that it was all I could do. My companions noticed it. The farther basement rooms were merely three meters away from me. They jumped to me, grabbed my arms and pulled to a safe cellar.

There was a first-aid station in the Simons Passage, something like a small hospital. Our fellow nurse and messenger from the days of the occupation was lying there, wounded some time ago. I was laid on a table. Obviously, there is no electric light, but my friend has a dynamo flashlight and tries to light up my legs. I am lying on the back and I am given a "strengthened" coffee to drink. For the time being I am in shock and, to tell the truth, I do not really feel the pain after getting shot.

I look down and see that the pants on the left leg over the knee are ripped and bloodstained, with a big hole in the middle. They cut my pants and a doctor starts to perform the operation. Actually he was a 4th year student of medicine, but in that hospital in the Simons Passage he was the deputy of a chief doctor.

After taking off my pants I can see a hole in my left leg. The doctor lifts the remains of the flesh and skin with tweezers and cuts the ripped fragments simply with scissors. He does not stitch the hole, he puts Rivanol on and bandages it. He gets down to the second leg. It is also wounded by a shot. There is a bullet entry hole, but no an exit one. The doctor examines the leg and says: "The bone is probably undamaged, but we have to get it off or it will screw up."

He examines the other side - there it is. It was the head of a defensive grenade, which hit the right side and almost went out. The doctor takes a scalpel and cuts a hole crosswise, then he wants to reach the fragment with scissors. All this is obviously performed without an anesthetic. After drinking the coffee, one nurse is holding my arm, so that I would not move. A friend with the flashlight holds the other one. Fortunately, I still do not feel too much.

The doctor cannot reach the fragment, the cuts a little deeper, gets hold of the head with special scissors and takes it out. He throws it into a kidney-shaped basin and says: "You'll take it in token of remembrance, won't you?" And indeed I took it. Rivanol again, a dressing. The doctor says: "I am not sure whether the bone is undamaged. He needs to be transported to hospital. I do not want him here".

After such a statement of the doctor two companions put me on stretches and take to the hospital at 21 Dluga Street. There were lots of hospitals in the Old Town: 21 Dluga, 7 Dluga, 9 Dluga. Firstly, we need to get through to the school in Barokowa Street. In order to get there one has to run across through a ditch. The ditch is not deep and as my companions are running with the stretches, a part of them was protruding over the embankment. When we are half way there I can hear a heavy machine gun, which is firing at us from Krasinski Garden. He is firing from behind. I am lying on my back and see everything vividly. They are rushing forward, while the ground behind us throws up from the shots. They are firing from behind.

A man has sometimes very strange interrelations. I am lying on the stretches and think: "This German is poorly trained. We were but taught that one has to shoot in front of the moving target, then an enemy will come under fire by himself. And he is trying keep up from behind. The German stopped shooting as if he had heard me and shifts fire to the front of us. However, the field of firing also changed and the bullets go too high. When we got out of the ditch and were at the doors of the school, the bullets were hitting over the doors and we were being covered with plaster from the façade. We arrive at 21 Dluga Street. The companions leave me on the stretches and go to the basements where a quite big hospital is located. It turns out that it is full of the wounded and there is no place to put me.

I am lying on the stretches in the yard's gateway and see two soldiers talking with each other. All of a sudden one of them rolls up and falls down. The second one, surprised, shouts the name of the friend. It turns out that it was a sniper, a shot could be heard, although not very audible in this noise. The wounded is taken to hospital.

My companions come back and say that this hospital will not receive me, neither will the one at 7 Dluga Street - the both are full of patients. They were advised to transport me to St. Jacek, because there is a lot of space and they will receive me for sure.

wounded list in the Old Town hospitals

We arrived successfully at the church of St. Jacek. The companions found some space by the altar, in the intersection of the cross and the aisles. They put me on the floor in front of the steps to the altar. There is another wounded man lying on the steps above me. I look up at the high vault; the windows pulsate with red light - everything around is burning; There was a bombardment a while ago. Incredible acoustics - the moans of the wounded spread from every quarter. My first night in the church-hospital is over. I observe the pulsating shadows through the windows, and bombardments, the continuous bombardments.

Zbigniew Galperyn

My friends, who had carried me here, visited me on the next day. They brought an opened bottle of red wine. "You have to drink it up; you have lost a lot of blood." They also brought something to eat. I told them: "Listen, I do not want to lie here. I have not slept all night. I am thinking that this wounded man, who is constantly moaning, will roll down on me from these steps. Please, move me somewhere else." They told me to wait a moment and went somewhere to find me a place.

They found it on the left side of the main altar, in the doorway of a sacristy. The Sacristy had the shape of a low annex built on to the church. There were beds inside and an aisle in the middle. The beds were placed at the rear of the church, from the side of Stara Street, on which one could go out from the sacristy. A small building was adjoining the sacristy; it was meant for old people, which nuns was taking care of. The wounded were lying also there. In total, the number of the wounded at the church amounted to about 300.

The severely wounded were lying on beds and had drip-bottles with some tonic. The others were lying on mattresses on the. The companions joined the mattresses in the doorway of the sacristy and put me there. It was a more quiet place. The room was smaller and lower, without such an acoustics. Only bombardments could be heard. At that time the Germans bombed the houses on Freta Street. The command of the People's Army (pl. Armia Ludowa) was also killed then.

I lied at that church until the end of the August. On August 27th the St. Jacek's Church was bombed. When the bombs had fallen, I thought that the whole church went up. The Germans dropped the bombs with delayed fuse. One of them pierced through the roof and hit floor where I had been lying before and then exploded. It opened a hole to the catacombs.

The bodies of the wounded that were lying there were thrown about the church. I did not see that, because I could not stand up, but the others told me that the body parts were hammered into the walls, windows and bars by the power of the explosion. In the clouds of dust moans, shouts and calls for help could be heard. At that moment I realized that I was saved by a miracle.

The conditions at the church were very hard. My bandages had not been changed since the dressing of my wounds in the hospital in the Simons Passage. In the last days of the August the Barry's military police came to the hospital; elegant boys, splendidly armed with submachine guns, side arms. They had the task of leading all the walking patients and the staff out of the hospital. Only severely wounded and those who could not walk were to stay there. They were preparing for evacuation from the Old Town.

They took all the military equipment from the wounded that could not go with them. They found a side arm under the pillow of a boy that was lying on a bed. There was a hell of a row when they tried to take it from him. He said that we would not give it away and that he preferred to shoot himself in the head when the Germans would enter. In spite of his resistance the arm was taken away. They founded grenades by the other one.

They walked up to me. I did not have pants and boots any more. They took my camouflage suit and police belt. I was left practically in a shirt and briefs, covered with a blanket. They did the same to others. The hospital was to be changed into a civilian one. All the walking patients, Daughters of Charity in distinctive headwear, insurgent nurses and doctors walked out. We were left alone.

A moment later the Germans come. Accompanied by a Polish doctor and a priest, a German officer is walking through the aisle among the wounded. The doctor, who speaks German fluently, says that these are the civilians wounded in a bombardment and that the army has already retreated.

But after them the soldiers of Vlasov army enter. They are wearing German uniforms. One of them, seeing a lying young boy, loads a gun and says: "I saw you shooting at us. You are no civilian, but a bandit." The doctor begs the German officer to intervene. He gives an order and the soldiers let us be for a while.

A moment later another Germans enter, this time with petrol cans. They walked into the church from Stara Street, poured petrol everywhere and set the fire. The church is burning. We are choking in thick smoke while lying in the sacristy. There is no one to help us; all those who could walk had to go.

Fortunately, it turns out that the brother of one of the severely wounded and an old nurse, not a nun, stayed. He is walking on crutches. These two, sparing no efforts, take us out from the sacristy on Stara Street, on the back of the St. Jacek's church. From the other side come the news about the terrible scenes in the area occupied by the Germans. Some of the wounded, allegedly healthy, were taken and then the shots could be heard; a nurse that was being raped jumped out of the first floor and broke her leg. All this intensifies the anxiety among the helpless patients.

The sacristy is filled with smoke. The nurse who is rescuing us gives wet pieces of rag to everyone and tells us to put it to the face. Thanks to that we can breathe. They take me out pulling the mattress from the corridor through the steps to the street. There are piles of rubble everywhere. Other rescued from fire are lying nearby.

The most severely wounded that were lying on beds and had drip-bottles attached remained in the building. Unfortunately, they could not be saved. Soon the vault collapsed and those that remained there were burned alive. In 1946 their skeletons were found on the burned remains of beds.

Those two managed to save from fire several dozen people. We were lying on Stara Street for 4 days and 3 nights. A German was hanging about there. If someone had a ring, he would get from him some bread or sugar that he had tucked in a paper tube, or water. People moaned, firstly loud, on the second day a bit more quietly. It rained for a while. Days were hot, because of the burning walls and windows and at night it was getting very cold. I even had a blanket, but I did not have energy to cover myself.

On the fourth day we saw a nurse with a Red Cross band and a non-commissioned German officer walking from the side of the New Town. She was holding a Red Cross flag and clerics with empty stretches were following her and searching for the wounded. Someone told them that there was a hospital in that place.

They came to us. As it was stated later, there were 40 people on Stara Street. I was also put on stretches and two young clerics carried me down Mostowa Street up to Podwale Street. Then we went down Podwale Street. On the corner of Podwale and Kiliński streets stood the only undamaged house and the shops on the ground floor of it. There was a big sign over the one of the shops: "Tailor". Everyone waited in front of that shop before the further journey.

My stretches were also put on the ground. One of the clerics entered the tailor's shop and found pants in there, school ones in fact - long, blue pants. He gave them to me and said: "Listen, they will be of some use to you, when you will be walking again. You have nothing now, they will come in handy, for sure" I was a bit surprised, but also happy with the information that I would be walking again, that I would live.

The chain of the stretches set off in the direction of Krakowskie Przedmiescie Street. On the Castle Square I saw a column in three pieces and King Sigismund with a sword in the hand lying on the ground. We moved from Krakowskie Przedmiescie to Karmelitow Street.

In the area of Bednarska Street I saw on Krakowskie Przedmieście Street a crowd of people coming from Powisle District and the Old Town. Even now I can see a small girl led by the hand by her mother. People was carrying suitcases, in arms, in hands; some left them as too heavy. The girl was carrying a cage with a canary-bird. It was the most important for her, she did not want to leave it. The group of exiled was moving farther.

We entered the background of the Carmelite Church, where a seminary was. We were carried there. I was in shock. Beds with bedclothes, doctors in white gowns. I was laid to have the dressing changed. A doctor cuts the dressing with scissors and I smell such a stench that I turn my head away in disgust. From both legs pus is pouring into a kidney-shaped basin. The doctor bathes the wounds, but I still can smell a terrible stench. The doctor says: "You have not had your dressing changed for a long time." I answer: "Yes, it was not changed since long ago." All this was rotting. Something from the thick pants of navy-blue police remained in the wounds and all this rotted. I had my legs bandaged, they gave me food and laid in a bed on bedclothes. It was not until then that I felt pain and burning sensation for real.

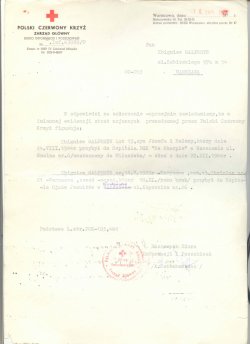

PCK (Polish Red Cross) document certifying the stay in hospital

translation: Paweł Boruciak

Zbigniew Galperyn,

born: 1929.05.18, Warsaw

rifleman, a soldier of Armia Krajowa (Home Army)

a.k.a. "Antek"

battalion "Chrobry I"

Copyright © 2010 Maciej Janaszek-Seydlitz. All rights reserved.