Barbara Gancarczyk-Piotrowska,

born on the 18th of October 1923 in Warsaw

the nurse of the Home Army

pseud. "Pajak" (=spider)

the 2nd platoon of the assault company

Scouts' battalion of the Home Army "Wigry"

Insurgent accounts of the witnesses

War Reminiscences of the nurse of the Scouts' battalion of the Home Army "Wigry" Barbara Gancarczyk-Piotrowska pseud. "Pajak" (=Spider)

2 -3 September

The end of August 1944. Warsaw Old Town still fights against the enemy ring, which gradually and systemathically tightens upon it. The Germans attack from all directions: from Zoliborz, Teatralny Square, Wola. The insurgent units, decimated, deprived of weaponry and ammunition, food and sleep, totally exhausted, are not capable of successfully repulsing the German attacks. How to face anti-tank weapon, planes, tanks? The attempt at breaking the enemy ring during the night from 30 and 31 August and the breakthrough were unsuccessful. The decision was made to evacuate the army and the slightly injured who could walk on their own - through the sewers to Srodmiescie. The civilians and the badly wounded remain in the Old Town. This is the order of the command. The way through the sewers is uncertain and difficult, it cannot be blocked simply because someone would lose consciousness with exhaustion, die or would not be able to walk any further. No one stays with the wounded. This is also the order of the command. We cannot afford any more losses. The nurses will be needed during the fights in Srodmiescie. The rules of war are cruel, inhuman, unforgiving. How hard is it to accept it. Some of us offer to stay with the wounded. "Prokop" declines. Our conscience and sense of duty is stronger than simply following orders.

The two of us, I and "Janka" abandon the group of nurses waiting for the passage through the sewers to Srodmiescie, and about 2 a.m. in the morning return to Kilinskiego Street 1, where in the cellars with nurse "Wisia" remained: "Stasiuk," "Robert," "Klecha," "Ikar" (Jerzy Szymanski) and Mrs. Starczewska, friend of Ewa Faryaszewska and Kazia Swiderska. Some other badly injured friends, among others, Andrzej Olubczynski "Lot," "Falinski" are in the hospital on Dluga Street 7. There was also a tiny hospital on Podwale Street 19, but everyone left it for the sewers.

The night of 1 and 2 September is full of anxiety and anticipation. We know that the units leave the outposts and go one by one to the sewers. The Germans can be here any moment. Yesterday we tried to learn how they treat civilians and the wounded. The accounts contradict each other. However, we believe, or rather want to believe, that they do not kill the wounded. Their numbers here, in the Old Town, are so great that one cannot even imagine the scope of a possible massacre.

Our boys try to stay calm and self-possesed. The presence of three nurses lifts their spirits. All of them wear civilian clothes, have appropriate papers, lie on the stretchers, ready to be carried out if it is necessary. We, the women, also wear civilian clothes, not camouflage jackets, though they do not fit our height and built. Janka is wearing my torn skirt (she could put it on only because it was torn), she is wrapped in a sheet to look decently, and I am wearing a girlish silk dress that reaches over my knees - we look funny and a little weird.

In the house on Kilinskiego Street 1, whose cellars we stay in, there is "Wigry" quarter on the first floor. We have to cover all the tracks. This is Professor Hempel's flat, now it is demolished, partially covered by rubble, the door- and window-frames are missing, but the whole flat survived by some miracle. We go there to sleep a bit, we are totally exhausted, and there is simply no place in the basement. In several rooms, there are camouflage jackets on the floor, German uniforms, rations from Stawki and rucksacks left by the friends who went to the sewers. This is "hot" stuff. While "Wisia" stays with the wounded downstairs, I and Janka hurriedly pack all these compromising things to sacks which we used to carry stuff from the warehouses on Stawki Street and throw them into the basement of a neighbouring burnt-out house on Podwale Street. The ceiling of one of the cellars was damaged, and we threw the sacks through the hole in the ceiling. There was no one there.

About 6 a.m. we notice the first Germans, coming from Zamkowy Square. These are single groups, 2 - 3 people in each, with weapons ready to shoot and machine guns. They dispersed to the gates of individual houses. We quickly return to our wounded and after a while we hear screams coming from the courtyard:

"Raus, schnell!!"

People hurriedly leave the cellars, docile and frightened, carrying their bundles and suitcases. The Germans form them into groups and lead towards Zamkowy Square. The Germans enter our courtyard. One can hear screams, people start to leave at once. "Janka," the only one of us who knows a little German, joins them. She asks one of the Germans:

"All right, so what we should do with the wounded. We are not able to carry them out from there."

He answers:

"This is what I would advise you. Carry these wounded out now, together with the civilians."

Janka replies:

"But there are five people there."

The German spreads his arms helplessly.

"Janka" talked to him for a moment and then returns to us:

"They told us to empty the cellar, the wounded have to be carried out." They are to check the papers on Zamkowy Square. Nobody knows what happens next. They give us 10 minutes. Everyone left in the cellar will be shot dead on the spot."

We do not know what to do. There are five wounded. And three of us. In addition, "Wisia" will not be able to carry anyone on her own. She is too weak. We cannot choose to leave anyone. It is all or nothing. We hold a quick counsel with our boys. Then we run to the hospital on Dluga Street 7. There we meet Father Tomasz Rostworowski. He helps us to make a decision - the only one possible in our situation. We stay here, but move all the wounded to the hospital on Dluga Street 7. There are several hundreds of wounded in this hospital. Most of them are civilians, a lot of women and children. Maybe we would manage to hide the insurgents among them.

A part of the ground floor and the entire first floor of the hospital are empty, as a result of constant air raids and fires all wounded people were moved to the cellar. The rooms filled with debris are quickly cleaned and prepared for the wounded brought here from nearby houses. One of the doctors takes the initiative: he organises medical staff from the remaining nurses and civilian women who volunteer to help. The latter often have their loved ones here. We find even some clean, white aprons and stick the Red Cross armbands to them. We introduce apparent "Ordnung" which the Germans value so much. We want to make an impression that the hospital fulfils all conditions to do its job: has well-organised staff, appropriate amount of medicine and food. It exists. It functions normally. There is no possibility that it should be closed down.

"Wisia" and Mrs. Irena stay on Kilinskiego Street 1, while "Janka" and I carry the boys on the stretchers one be one to the hospital. The basements and ground floor are occupied by the wounded. Only the partially damaged rooms on the first floor are vacant. During the Warsaw Uprising the wounded were carried downwards from the first floor because of bombardment.

One goes to the first floor by the staircase from the side of Dluga Street, where the entrance gate is. Having crossed the large hall, we put the boys on the first floor in the second room from the staircase, in the corner furthest away from the entrance, so that they are not conspicuous. Their young age, characteristic gunshot wounds in the legs could make the Germans suspicious that they are insurgents. All of them lie on the stretchers, next to each other, covered by blankets. In the meantime, new wounded are carried here from nearby houses. The room gets filled so quickly that soon there is no space left for Kazia Swiderska next to our boys. We had to put her a bit further away.

|

|

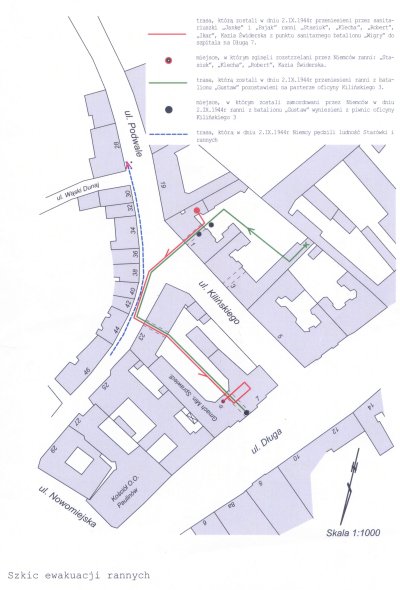

The way of evacuating the wounded "Wigry" boys from Kilinskiego Street 1 and the wounded soldiers from the battalion "Gustaw" from Kilinskiego Street 3;

on the right, the same situation marked on air photograph taken in January 1945.

In the hospital, there are very few doctors, and the majority of nurses has left it as a result of the insurgent command's order. Edward Kowalski, a medicine man who speaks perfect German, remained there.

We get clean, white aprons and Red Cross armbands. These are our uniforms which are to protect us from being escorted by the Germans with the civilians. We are the members of the hospital staff. Everything possible is done to prove to the Germans that the hospital has every chance to exist, it has medicine, dressings, there is medical staff. They even started to cook and distribute soup, doctors or nurses make dressings.

"Wisia" stays with the boys, and I and Janka are busy gathering food and dressings. We have no idea what awaits us or how long would we stay here. We have to equip ourselves with the most indispensable things. Some of them remained in the quarters of our battalion. From time to time some German slips me a packet of cigarettes, another a bottle of wine, saying: "Für kranken." Some of them who speak perfect Polish and as it turns out are from Silesia lead us to an abandoned first aid station on Kilinskiego Street 5 and stuff the aprons with medicine, bandages, cotton wool, saying:

"It would be a pity to burn it, it will be of use for the injured."

Their friendliness encourages us. We ask them what they intend to do with the wounded.

They mutter something about evacuating the hospital or leaving it in its place. One of them tells me straightforwardly:

"I am Silesian, so also a Pole, don't you worry, Poland will exist anyhow."

There are such types, and there are also others. In general, it is a mix of criminals, members of the SS, Ukrainians, Wehrmacht soldiers. It happens so, that they rush into the rooms, come to the young, tear off the blankets, sheets and look at their faces. It is obvious that they are looking for the insurgents. We guess that they have orders to murder them. Sinister questions are asked:

"Sind Sie Bandit?"

One of the Ukrainians seems particularly threatening to us. He is a short, stocky blond man, and speaks perfect Polish. We watch his extremely brutal behaviour towards the wounded. He is obviously itching to hit or kill someone, one can see it because he has his gun in his hand all the time, with his finger on the trigger. He would be the first to start a massacre, if an order was issued... Heart sinks when he approaches us. We try to cover the boys from his evil eye, by sitting next to their stretchers, hiding their faces behind the blankets. So that he would not see how old they are. When he comes closer, we explain that these are civilians. He does not believe us much.

Father Tomasz Rostworowski and one of the doctors who speaks perfect German try to convince the Germans that the hospital is a civilian one. They can be seen from the window on the first floor, how they negotiate with some high-ranking officers.

The situation, which was initially uncertain, begins to gradually become clear. Hope fills the heart. So much time has passed since the Germans entered and apart from isolated incidents of shooting, there were no mass executions, so maybe the rumours about evacuation are true. Maybe everyone will survive? In any case, these who are in the hospital, seem to be relatively safe now. However, we know the situation of the Old Town too well to be aware of the fact that outside the hospital the cellars of many houses are full of badly injured people. The slightly injured and these who can walk on their own, went to Srodmiescie through the sewers.

The lucky ones, who have members of their family by their side, have already been transported to the hospital. What about the others? Left without any care, they cannot move from their pallets on their own. The situation is desperate. The Germans demand that everyone leaves the cellars, otherwise they threaten with shooting dead. With their flamethrowers, they set fire to each house, one by one, even to these which are partially damaged. The wounded are in danger of being burnt alive, or killed by a bullet or a grenade at best.

The civilians leave their shelters in a hurry. We cannot count on their help. Bundles with the remains of their possessions are more important for them than the fate of the wounded.

There are not enough nurses in the Old Town! We consider it our duty to give aid to the very end. We leave the "Wigry" boys under the care of "Wisia" and Mrs. Faryaszewska, and go downstairs. On the courtyard of the Ministry, we meet Father Tomasz Rostworowski. He also tries to save the wounded, carrying them out from nearby houses and transporting them to the hospital. He seems somehow worried, distressed. And he always impressed me with his exceptional composure.

I remember Father Tomasz from the first part of the uprising, how he merrily sang soldier's song with us, I remember him also as a courageous and extremely sacrificial soldier, who carried out the wounded away from the field of fire, I remember him as a priest who said "insurgent" Masses, interrupted from time to time by a Nebelwerfer explosions, which demolished the walls of makeshift chapel; as the one, who made the sign of the Cross over the dying, and consoled the wounded with warm, heartfelt words. It was Father Tomasz, who during the retreat from the Old Town, firmly rejected the offer of coming to Srodmiescie:

"No!!! I will not abandon my wounded to the very end!"

Father Tomasz stops us. We sense a quaver in his voice when he says:

"Dear girls, you have to go to Kiliniskiego Street 3, the boys from "Gustaw" lie there in the annexe, maybe you would achieve something, I cannot help them on my own."

I and "Janka" pull the stretcher from behind a body of a fat woman, the body falls with a bang. There are some other corpses on the courtyard. Together with Father Rostworowski, we run to Kilinskiego Street 3. We go to Podwale Street. The front of the building on Kilinskiego Street 3 is damaged by bombs. One reaches the annexe by the gate and a spacious courtyard on Kilinskiego Street 1.

There are Germans and Ukrainians everywhere. The upper part of the building is burning. The fire consumes the second and third floor. Father Tomasz leads us to a room on the ground floor. In the entrance, there are two German soldiers. The priest, who speaks perfect German, asks them:

"Can we go here and carry out the wounded?"

They allow us. I and Janka go inside. Father Rostworowski, seeing that it is done, goes away to save other wounded. We go straight ahead a long corridor to the kitchenette located at its end. On the left side, through broken doors to the rooms, we can see the Germans: they turn the drawers upside down, rummage through the wardrobes to find more valuable things.

The wounded lie in the small kitchen. Two on beds, and one on mattress next to the wall. They are young boys, 18-20 years old. They cannot move: badly injured, mostly with their legs injured, bandaged up to their waists. One of them has a hand in a splint. This is "Firlej" (Stanislaw Bielanski), a very brave boy. Some members of the SS stand next to them. The wounded do not react to the brutal words of the Germans, who jump upon them with machine guns. At the sight of two girls in white aprons, with stretchers under their arms, flash of hope shines on the boys' faces.

The Germans - there are four of them - are also surprised by our sudden appearance. They ask a stupid question:

"Why have you come here?"

Janka answers in German, undaunted.

"Why have we come? The house above them is in flames, we have to carry out the wounded. Should they burn alive, or what?"

"These are criminals, and they will be shot dead in a moment anyway. You have to get out of here."

We are at a standstill. Janka explains that these are civilians, rescued from the ruins of the bombarded house nearby. The age of the boys and characteristic gunshot wounds contradict her words. The German becomes furious.

"Yes, there are only "civilians" and "rescued from the ruins" for you.

He jumps towards one of the wounded and puts a machine gun under his nose:

"You know very well how to use this weapon. You shot to us many time with this. Isn't it so? I know, you got it from airdrops!"

They boys are petrified. They do not say a word. They do not try to explain themselves. Maybe they do not understand German?

"Janka" takes the initiative of their defence. Father Tomasz is long gone to save other wounded. "Janka" does neither ask nor beg. She tries to breaks the resistance of a particularly obstinate SS officer by using factual argumentation. The German does not yield, but it is obvious that this quarrel begins to amuse him.

"Janka" tries something completely different. She makes an effort to smile mischievously, a bit mocking, a bit coquettish. She relieves the tension for a moment, winks at me. However, every attempt we make to come close to any of the injured and carry him from the bed to the stretcher meets with strong opposition. The struggle has been going on for quite a long time. I do not take part in it. I do not speak German. I stand on the sidelines.

Suddenly I hear that "Janka's" voice starts breaking. Are we losing? I cannot accept the thought that the ones who are in front of me, so close, would be murdered any moment, here in their beds. It breaks my heart. Against my will, the tears come to my eyes and slip from my lids. I try to control my feelings. No one can notice my weakness. I hear German gibberish next to me:

"Warum Weiner Sie?"

I do not understand the words, can only guess their meaning. I shake my head. "Janka" understood my gesture. I hear her normal, composed voice - words spoken in German:

"She isn't crying at all, and the tears... they are caused by the smoke, it is everywhere... the smoke stings her eyes... the house above us is burning..."

The German looks at us in a weird way, and then bursts out in a violent, nervous laughter, which stops suddenly. We do not know what it means. Seconds pass, full of anxiety. And then the words reach us, as if the proof of regained humanity, spoken by the member of the SS in broken voice:

"Ihr seid brave Mädchen... also meinetwegen nehmt die Verwundete mit."

"Janka" announces the victory with a wink and a smile:

"Come on, Baska, give me a hand."

Later I asked "Janka" to translate the last sentence. The member of the SS said:

"You are brave girls, you can take the wounded."

This approbation from a member of the SS, a murderer, seemed to us something unimaginable.

We put the stretcher next to the bed. As first, we take "Firlej" who seems to us to be most in need. His both legs are immobilised, bandaged up to the thighs, he also has a hand in a splint. Physical pain, which he feels by every move, is nothing in comparison to what he has been through recently. We carry him to the Ministry building and put on some captured mattress in the gate overlooking Dluga Street. It would take too much time to carry him to first floor. We must hurry to get the rest, before the Germans change their mind.

Only two are let. None of them wants to be the last one. Our reassuring words that we will come here once again, that we will not leave anyone, do not help. While we carry one of them on the stretcher, another one, with his knee injured, springs from his mattress, hangs on my arm, and in this way, limping on one leg, goes with us to the hospital on Dluga Street. We also leave them in the gate overlooking Dluga Street.

There we crave to see our friends from "Wigry". Drop in for a moment, ask if they need something, reassure them that we are nearby. They are on the first floor. "Wisia" does not leave their side for a moment. Both rooms are filled by the wounded. There is almost no free space. One has to walk carefully among the wounded, so as not to jostle anyone. The boys are calm and composed. Only sixteen-year-old "Klecha" cannot hide his feelings. Fear emanates from his restless eyes. He wanted so much to go to Srodmiescie through the sewers. "Stasiuk," "Robert," and "Ikar" are older, they are over 20 years old and have some experience of German occupation. They are hardened. They even try to smile when they see us. We kneel down by their stretchers for a moment. We are out of breath, grimy and our hair is in elflocks. They see how tired we are. And they encourage us to take some rest. We explain that we will be back soon, but for the time being we have some things to do. We reassure them that everything is all right. We deny the rumours about isolated incidents of shooting dead. It seems to us that they are a bit cheered up after our visit. We did not know then that we saw them for the last time.

We run through the hospital's courtyard. We go to Podwale Street. It is hard to squeeze through the crowds of civilians, who go incessantly here from the Market Place towards Zamkowy Square. The street is bumpy, covered with debris, there are bottlenecks in the narrow passages.

In front of the hospital, in a bomb shell crater, we notice two elderly women, sitting next to their bundles. Apparently they have fallen there and cannot get out. We need to help them. They are wearing black, silk dresses with lace. On their heads, there are enormous hats, one with a veil, and another with violet silk ribbon. Apparently these are their best clothes which they did not want to leave behind. Maybe they fit in the theatre, but here? This view is so surprising in contrast to hungry, haggard people making their way through the ruins of burning streets that it makes one laugh. The elderly women are frightened. I help one of them to her feet. She can hardly stand. She catches hold of her bundles and sits down again. Janka raises up the second woman. The same story. They are unable to carry even a part of their possessions. We wonder how they managed to carry them here. In spite of our protests and exclamations they do not want to abandon anything. We leave their to their own fate. We have no more time to lose.

The wounded who need to be rescued from the burning house on Kilinskiego Street 3 are waiting for us. The fire reaches to the first floor. In the dark cellars, there are several boy scouts from "Gustaw", and in the neighbouring house three people, among them nurse "Kozak" (Halina Sliwinska) with her leg amputated. The latter is in a very bad state as a result of tetanus infection. The way there is convoluted, through winding corridors, deserted cellars. We have only some matches at our disposal, and they burn and go out in a moment. We are lucky as some non-commissioned Wehrmacht officer with a torch turns up and illuminates the way for a moment. In one of the cellars, which is partially demolished, we noticed a chained up dog. The German frees it and smacks his lips. The dog does not move. There is nothing to be done, it stays here. We leave the first three people in the gate opening to Podwale Street.

Next, we carry out the boys from "Gustaw." They lie in the cellars. Their nurse goes to meet us. We go downstairs from the courtyard. The match illuminates gloomy interior. The cellars, one after another, stretch along the long corridor. Along the road, I slip on some treacherous stairs and fall. The wounded, left alone in the darkness, remain silent. They do not want to give themselves away to the Germans. After a moment, when they hear our calls, they make themselves heard.

The appearance of Polish nurses in white aprons and Red Cross armbands is deliverance for them. Everyone wants to reach the hospital as fast as possible. We make around each cellar to check how many of them there are. It turns out there are several of them. All of them are badly injured - shot in stomach, legs, breast. In one word, those who could not be evacuated to Srodmiescie. We carry them out one by one. We put them on the stretchers almost blindly. The matches light and go out immediately. Sometimes we take hold of an injured limb. We hear a hiss of pain, and sometimes a curse. We try not to hurt anyone, but is it possible in such condition at all?

Luckily, the German with a torch appears again and this time agrees to help us. The stairs are hardest to cross. While the first one goes bent to the ground, the second one tries to hoist the wounded as high as possible so that he does not slip off the stretcher. When we are half way there, I feel that something binds my legs. I try to keep my balance with all my strength. Janka, disoriented, not knowing what is going on, curses and so do I. It turns out that my both shoulder straps ripped and because of this I almost fell down with the wounded.

|

|

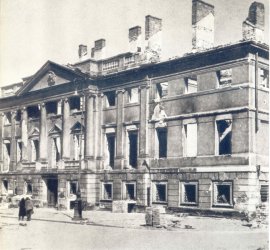

Kilinskiego Street 3 where the wounded from "Gustaw" were lying.

In the photograph, the sight during the uprising, when there was a field cemetery (photo by W. Chrzanowski);

on the right the sight after the cemetery's exhumation (photograph by Maria-Tadeusz Gancarczyk 1946).

The marked window shows where the injured were lying.

We put the injured in front of the entrance to the building, on a pile of debris. There is no time to transport them to the hospital one by one. We need to hurry up, as the fire spreads more and more. The first floor is already burning. The smoke whirls above the wounded and sparks fall on their heads. And they, in bloody bandages, in their underwear, some of them half naked, do not even ask for help... they try to crawl on their own, only to be further away from the unbearable heat. Some of them lift themselves up on their elbows, others push their bodies in some other way, just like they are capable of doing. There are fifteen- and sixteen-year-old boys among them, almost children.

It breaks my heart to see it. What an enormous amount of human misery. But the Germans are not moved. They laugh at them, wave their guns, call them criminals. They do not shoot yet. Maybe they are stopped by our presence? And maybe they think that we are allowed to carry out these wounded. One by one, in part on the blankets and stretchers, we carry all of them to the gate on Kilinski Street 1. It is quite close to the hospital. The last stage seems the easiest one to us, even though we are terribly exhausted. We feel all our muscles tremble, our palms are swollen from carrying the wounded. Heart is pounding, sticks in my throat , it is hard to breathe. It seems to me that we left the worst things behind and only the transport to the hospital is in store.

It is about 2 or 3 p.m. We are so tired that we almost do not speak to one another. But what is this? From the gate opening to Podwale Street, we see the doctors and the wounded who can walk on their own, led by the nurses - they are all coming from the hospital. We are disoriented. We have not expected this. No one can answer our questions: where to? Why?

We notice doctor Kowalski and "Wisia" with wounded "Ikar" who leans on her arm with one hand, and with the other on a broom. She carried them out from the first floor in the last moment. We ask "Wisia" what is going on. She is dead tired. She repeats all the time:

"I don't know anything, I don't understand... go save the others... they are left in the hospital..."

We hear isolated shots, screams. There is no doubt that it is an execution. Only with difficulty do we manage to break through to the hospital's courtyard. There is total chaos here, turmoil among the remaining wounded and medical staff. The nurses leading the wounded are still coming, the wounded are still crawling on their own. We reach the staircase leading to the first floor. There are some Germans with guns in the entrance. Among them there is a woman in a white apron, who stretches her arms and firmly forbids us to enter:

"You cannot go there."

We are mad at her. She is Polish! So why is she stopping us? Later on, we understood that she wanted to save us from imminent death, but then, filled with despair, we did not realise it.

Oh, these unbearable single shots!

We must reach our boys at any cost. The Germans do not even want to hear about letting us go upstairs. Nearby we notice a high-ranking officer, about 40 years old, in an impeccable, elegant uniform. "Janka" addresses him in German. She explains that we want to save our family, father, brother and... she infuriates him. Foaming at the mouth, the officer curses and threatens us:

"You should be shot dead, too, at your place women and even children brought weapons to these criminals... all of you should be shot dead..."

We run to the street through a gate on Podwale Street. The wounded are still coming and crawling out of the hospital. We hear someone beg for help. Not yet...

In the gate on Kilinskiego Street 1, we notice the same non-commissioned Wehrmacht officer who had a torch and searched the cellars for the wounded with us. His friendliness which he showed then emboldens us now. We ask him for help in saving our loved ones left in the hospital. "Janka" promises to give him a golden bracelet, the German is reluctant, maybe he does not believe that he can help us, or maybe he does not want to take the risk? In a moment it would be too late. We do not give up... we hale him... "Janka" pushes him from behind, I drag him by the sleeves of his uniform. Initially he resists, but then he goes on his own without any hesitation.

By the entrance to the hospital, he explains to the Germans who want to stop us that we are coming with him. They let us go. We have to squeeze through the crowd of wounded who go, hobble and crawl away. It is blue from uniforms on the courtyard. Apparently there was an order to bring almost all soldiers here. We do not notice any wounded among them. A moment earlier, there were plenty of them here. The sounds of shooting are unbearable. Terrible things are happening. I go almost with my eyes closed, I do not want to see anything. It seems to me that the execution on the ground floor and in the cellars has already started. I try to turn off the senses of sight and hearing. To see nothing, to hear nothing... To cross the large courtyard as fast as possible and reach the first floor.

We stop in the gate. The non-commissioned officer, who accompanies us, comes to a group of the members of SS which stands next to the entrance downstairs. He negotiates with them. We watch him form afar, standing aside. We have no courage to raise our eyes when he addresses us, saying: "There is no use in going there."

They are dead! Only two hours ago we reassured them:

"Be calm, we won't leave you... as long as we're by your side, nothing bad can happen to you..."

All this time we believed that the ones in the hospital are safe, and it is those who remained in the cellars without any care whom we should rescue. Were we too haughty, or did we naively hope for the best? The breakdown that falls upon us in this one moment is the greater, the greater was our faith in our managing to save them. We would be plagued by the qualms of conscience long afterwards, regretting the fact that we had lost the last chance of rescuing them.

We have no strength left to walk, our legs have turned to jelly. We stagger like drunks, trip. Suddenly, in the passageway to Podwale Street we meet Father Tomasz. He has just come out of the hospital cellars, where he tried in vain to save a priest he knew. We cling to his hands, looking for help, reassurance, salvation. But he is heartbroken too, and just like we do repeats frantically:

"This is horrible, this is unbearable."

He absolves the dying by making the sign of the Cross in the air. Hand in hand with Father Tomasz we leave the hospital. We leave the hospital staggering, crying, feverish. And behold: I see a picture which will stay in my memory forever. This is the face, or precisely, the eyes of a young German soldier who stands in the entrance to the hospital. The eyes are full of fear and compassion. I will never forget these eyes.

|

|

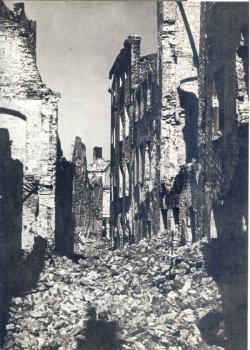

The hospital ruins on Dluga Street 7 in 1945 (photograph by L. Sempolinski on the left, by Maria-Tadeusz Gancarczyk 1946 on thr right)

In front of us, on the debris-covered street with a bomb shell - the wounded. These are the ones who left the hospital on their own, but they cannot go any further without help. The ones who were hurriedly carried out of the burning houses and then left to their own fate.

The wounded are crawling, Father Tomasz helps two men to stand up. "Janka" takes from someone a little girl with her hand amputated. I even do not try to shake my hand with them. I am totally numbed and have no strength left. Anyway, what is the point? A few metres away, in the opening of Waski Dunaj Street, the crazed Germans finish off the wounded, snatching them away from the nurses who were leading them. Oh, if only all this torment could end.

Waski Dunaj Street in the opening of Piwna Street (photograph by L. Sempolinski) |

Rycerska Street where the Germans murdered 70 Poles on 2 September 1944 (photograph by L. Sempolinski) |

Suddenly I see a man running from a house nearby. He is an elderly, grey-haired man, and is carrying a young girl in his arms; she must have been carried out directly from her bed, since she is half-naked, covered with a sheet and bloody bandage on her breast. He is at the end of his tether and cannot carry her any further. In his eyes I can see despair and begging for help. The girl is 18 or 20 years old. It is obvious that the man will not go far with her. I run towards him. We hold our hands together and put the wounded girl on this makeshift chair, carrying her towards Zamkowy Square.

The girl faints several times, slips from our arms, we have to stop and revive her, hitting her on her face. It is easier to carry someone who is conscious, than someone who is inert. The way is very troublesome and difficult. One goes through the heaps of debris, passing the shell holes and collapsed houses. And the Germans constantly press people to hurry up, finish off the slower ones and burn others alive, firing the firethrowers.

Podwale Street directly opposite Kilinskiego Street. Behind the barricade on the left, the opening of Waski Dunaj Street (photograph by W. Chrzanowski)

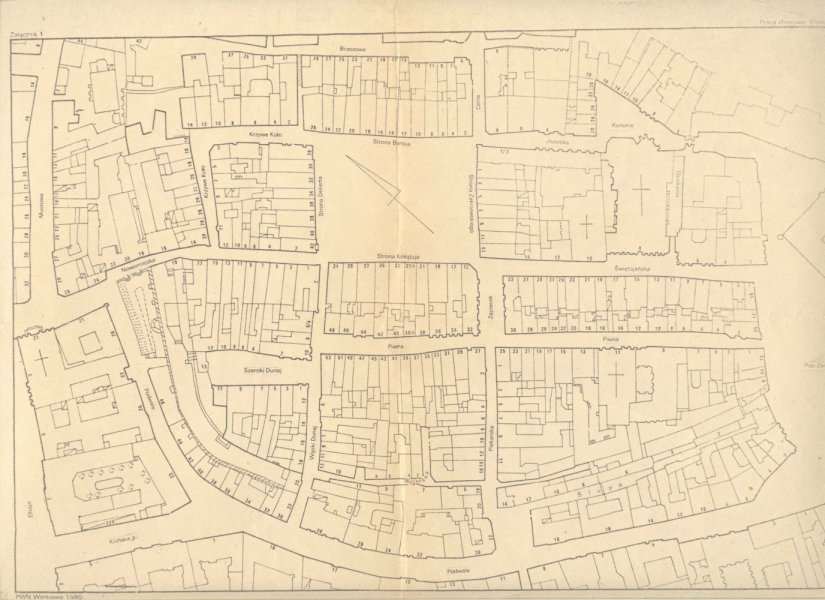

The map of the area of Podwale Street. It looked fundamentally different than it looks today.

The street was built-up on both sides up to Zamkowy Square. On the side of Nowomiejska Street there was no Barbican.

There is a short stopover on Zamkowy Square. I can see "Janka" giving back the girl she carried. Apparently her family has been found. We are surrounded by a gang of Russians. They rob everything they can. We do not have anything valuable on us, but some other people have wedding rings, earrings, watches. People ask a German officer for help. He prevents further robbery. On Zamkowy Square I see Father Tomasz for the last time. Later, he vanished suddenly from my sight and I believed that it was here where he was murdered.

I learned later on that Father Rostworowski, when we were driven through Mariensztat Street, fell into the ruins of a house on Zrodlowa Street and stayed hidden there for another month as a Warsaw Robinson. He was discovered by the Germans after the city's surrender and then he was allowed to come out. It was almost a miraculous survival.

"Janka" ran further along Mariensztat Street as she did not see me, and I was left behind. From Zamkowy Square, we are driven along Mariensztat Street, downwards, towards Vistula. Along this route, there are Ukrainian outposts guarding the people, so that no one can run away sideways. One of the Ukrainians shows something to the other, waving his pistol.

In a distance, I see a young woman carrying on her back a man who is taller than she is. She is bent in half, and holds his hands... his legs are bandaged up to thighs and hang inertly. She has to make breaks, throw up the body which slides from her back; then the hands of the wounded clutch nervously on her neck, stopping her breath. I recognise them... these are "Janka" and "Ikar." The Ukrainian comes a few steps closer, machine gun in hand, as if he was getting ready to shoot a series in their direction. And they are walking so slowly... so slowly... Suddenly, they disappear behind a corner. I can see them no more. This time they were lucky.

From Mariensztat Street we turn into Sowia Street, and then into Bednarska Street, upwards, towards Krakowskie Przedmiescie. This upward part is the hardest one. I trip every now and then, staggering. I carry the wounded woman with great difficulty. Out of necessity I must follow her father, who finds superhuman power in himself to save his daughter. In the opening of Bednarska Street to Krakowskie Przedmiescie a German is screaming and waving in our direction. I do not know what he means. He stops us. He pulls a young man from the ranks, and - outraged - points at me and orders him to carry the wounded woman.

Nearby, in the Carmelite monastery, there is a hospital to which the wounded are allegedly evacuated, outside Warsaw. Is it true? After what we have seen on Dluga Street...

We gather on the small square near the Carmelite church. Several soldiers stand in front of us. Machine guns pointing towards us. A silly feeling, just like before execution...

I look for "Janka," "Wisia," "Ikar," Mrs. Faryaszewska. I cannot find them anywhere. They must have decided to go further, towards Wola, following the civilians. Maybe I will manage to catch up with them. I run through Krakowskie Przedmiescie. The insurgents allegedly shoot along this street, from Staszic Palace. Actually, I go on my own. I cross Trebacka Street through Pilsudski Square. There, two Russian soldiers stop me. They ask me questions in Russian. Because I am wearing a white apron with Red Cross armband, they assume that I was a nurse and helped the "criminals." They suggest I stay with them. A larger and larger group of soldiers surrounds me. It is hard to cut one's way through them.

At last, a German officer disperses them with his hand and severely orders me to go further. In the Saxon Garden I come across elderly women resting on the grass. I sit down next to them for a moment. I am totally exhausted. This is my reaction to the horrible experience. I realise that actually I am not needed anymore since the ones whom I tried to save were murdered anyway. At the same time, life instinct appears. I have enough of death, enough of fear, I have seen too many tragedies, too much suffering, and - what is worst - human bestiality. I want to get out of here as fast as possible, get out of this hell... before someone does me in along the way. I tear off the white apron - so that I would not be suspected of aiding the "criminals." I help the elderly woman to her feet, arm in arm - maybe they would not have the courage to stop me along the way.

We drag at a snail's pace. The elderly woman cannot walk any faster, but this tempo suits me perfectly. Elektoralna, Chlodna, Wolska Street... Ruins and charred remains of houses are everywhere, not even one house survived. The city is dead, a desert. I don not believe that life should ever return here.

Elektoralna Street in the opening to Chlodna Street (photograph by L. Sempolinski)

Along the route, there are checkpoints of military police, Ukrainians, Russians. Some of them took out some chairs, armchairs or tables to the street. They sit on the tables, sipping beer or orangeade. Seeing this makes me even more thirsty. The heat is unbearable. I have not drunk anything in the last 24 hours.

We sit down on the kerb on the intersection of Chlodna and Wronia Street. We have some rest. I share a glass of water with the elderly woman. I give the glass back to one of the soldiers. He starts talking to me. He points towards the neighbouring gate as if he wanted me to follow him. It is hard for me to understand him - he says something about war prisoners, about insurgents. I follow him, keeping an eye on him all the time. I glance at the courtyard. It is empty. I stop. Suddenly I feel that someone catches my arms up to the elbows from behind. I resist with all my strength. Two of them are tussling with me now. They want to drag me inside, tear me off from the iron gate to which I hang on tightly. They do not manage it. I scream desperately; "No, I won't go there!" They give in. Laughing, the let me go.

I run to the elderly woman, who is sitting. I help her to stand up. We go on. We are passed by cars, wagons carrying the wounded and the elderly towards Wola. I put the elderly woman on one of them; she can hardly walk anymore. I go on my own. I speed up. It is already dark when I reach the church of St. Adalbert in Wola. The people are huddled, sitting on the floor. There are a lot of women and children here. Among them Ukrainians and members of the SS roam about. I do not like it here. I go outside. I find neither "Janka" nor "Wisia."

A large group of people gathered in front of the gate catches my attention. In threes or fours they are getting ready to depart. They hold some papers in their hands. They speak only in Russian. I assume they are Russians - "the white" - who were considered the allies of Germans during the war. I decide to slip away with this group. Taking advantage of the inattention of a gendarme who checks the documents by the gate, I get around him. They lead us towards Wolska and Bema Street. After the flyover we turn left, towards Warsaw West station.

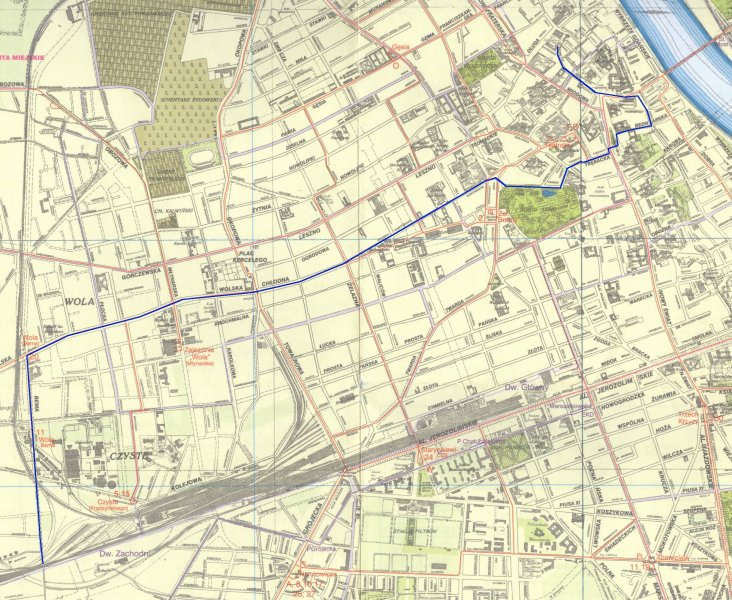

The route through which on 2 September 1944 the hospital staff from Dluga Street 7 was driven

together with the wounded and civilians.

The platforms are filled with people expelled from various Warsaw districts. They await the transport to Pruszkow. I hang around them, looking for friends and close ones. I feel terribly alone in this crowd of these strange people. I think about my parents, about my sister. They remained on the other side of Vistula, in Saska Kepa. What is going on with them now? I try to start a conversation with someone.. I sit down next to a young pregnant woman. She is here with her mother.

When the train comes, I help them to load their numerous bundles into the carriage. I sit down in the same compartment. The night is cool. I am shivering. The young woman gives me her coat so that I could cover myself with it. The mother is very displeased, and mutters that they can take care of themselves on their own and do not need anyone's help.

The train stops in Proszkow in the factory. Here, just like on the Warsaw West stations, crowds of people. I cannot stop thinking about looking for "Janka" and "Wisia." Nearby in the shadows, I notice a wagon filled with the wounded. This wagon will show me the way to the hospital barrack where I will surely find my friends, Mrs. Faryaszewska and "Ikar." I give the borrowed coat back to its owners, and head towards the wagon which begins to move. It is loaded to the brim. Going behind it, I must support an elderly woman who sits on the very edge of the wagon. One moment, she slides into my arms. The coachman stops the horses. I load the woman back onto the wagon, and taking advantage of the situations, sit down next to her.

We stop in front of a large shop floor. Here they gather the wounded, nurses, the sick and the elderly. It is dark, here and there I can see candle-ends burning, from time to time a match flashes. The people lie down on the concrete, others loiter around looking for a free corner to sleep in. I also crouch down next to the wall, and nap, holding my knees in my hands. Suddenly, something like "Janka's" voice reaches me. Initially, it seems to me that I am dreaming. I prick up my ears, and hear her laughter - resonant and characteristic. Though it is difficult to notice anything in this darkness, I follow the voice.

Yes, these are really "Janka" and "Wisia" - they carry chipboards to make a bed. There are also aunt Faryaszewska, "Ikar" and other wounded boy whom I do not know. We hurl ourselves into each other's arms. We cry for joy. Aunt Faryaszewska says: "Basia, I was so worried about you, when you got lost... I saw the Germans and Ukrainians drag young women from the ranks... How good that you're with us..." Yes... in such moments it is so good to be among reliable, faithful friends.

"Wisia" tells me what happened to her and "Ikar" from the moment they left the hospital on Dluga Street:

It was all right in the afternoon, when the Germans ordered the entire staff to gather on the courtyard. They assumed that some orders would be issued. "Wisia" who was by the wounded on the first floor, did not go downstairs. We watched from the window what is going on there on the courtyard. Gradually, it was filled with slightly injured. Also, the medical staff gathered almost in its entirety. One moment, this group of people began to prepare to depart. "Wisia" had a premonition and ran downstairs. Here she learnt that the Germans ordered everyone to leave the hospital and abandon the badly injured. But why? And what is next? Nobody could answer this question. One could only guess at the answer.

"Wisia" ran upstairs again. Unfortunately, in the entrance to the ward on the first floor there was a German who did not want to let her pass, blocking her way with his gun. She pushed him away with her hand. The barrel tore her apron and scratched her body, but "Wisia" was already inside, she reached the boys, caught "Ikar" who was lying on the edge, and told the rest that she would bring them downstairs one by one. "Ikar" who was wounded in both legs, walked with difficulty. But the fear gave him strength, and "Wisia" held up his body as hard as she could. Along the way, she got hold of a broom on which he leant with his good hand.

The member of SS, who threatened her with a gun, stood aside. He was impressed by her courage. When she ran once again to fetch the rest of our friends, there was a group of Germans on the landing. This time it was too late. She realised that she would not be able to do it on her own, but she met me and Janka in the gate on Kilinskiego 1, among the wounded. She hauled "Ikar" over to Mariensztat Street. This was where "Ikar" broke down. He sat down on a heap of debris and announced to her that he would go no further. The pain of wounded legs was unbearable. Neither "Wisia's" insistence nor the threat of death could help.

Deliverance came unexpectedly in the person of "Janka." On Zamkowy Square a family member took from her the little girl, whom she was carrying. She ran forwards, following a group of the wounded, expecting to find "Ikar" and "Wisia" among them. They could not have gone far. In fact, she noticed them sitting in the ruins of Mariensztat Street. "Ikar" was totally resigned. The Germans were coming. They went from the direction of St. Anna's Church with firethrowers. Others with guns. Along the street there were the wounded who had no strength to go further. One moment, a fire sent towards those who stayed behind flashed. "Janka" jumped up and started to look for some stick to make a stretcher from her apron, but she did not find anything in the ruins. One had to flee as fast as possible.

There was no time to lose. "Janka" said:

"No, Jurek, you can't stay here. I'll give you a piggyback ride."

And she carried him on her back. He was not her brother, nor her fiancé, he was not even from our unit. He was merely lying with our friends in our little hospital. She brought herself to do something which is hard to believe.

She carried him through Mariensztat Street, then she turned into Sowia and Bednarska Street, which was very steep and led upwards. There was a stopover by the Carmelite church. There one could leave some of the wounded, there was a hospital there. These wounded, as it turned out later, were all transported to the hospitals in Milanowek outside of Warsaw. Jurek did not want to stay there. Janka asked him:

"Do you want to stay here, or go on with us?"

"I want to go with you."

After what he had seen on Dluga Street, he did not trust anyone. "Janka" said then:

"So I'll carry you."

Janka carried him on her back. She went bent over and he clang to her neck. Then she told him:

"You know, 'Ikar' I can't carry you any longer like this, it's going to hurt, but I must carry you holding your knees, I won't manage it otherwise."

His legs were wholly bandaged. She carried him across Pilsudski Square, the edge of Saxon Garden, Chlodna Street, next to St. Borromeo's Church. There was a short rest there. It was a dangerous place, the Ukrainians drove people inside the church. "Janka" took "Ikar" on her back again and they went through Chlodna Street to Zelazna Street and then to Towarowa Street.

Finally, they came across a two-wheel cart with a shaft, on which the wounded were crammed. A robust man was pushing the cart. In spite of the wounded's protests, Janka put "Ikar" on their heads, though the price was that she had to push the cart. She was pushing it together with Wisia and the man. Later, the man disappeared and they pushed the cart on their own. The cart got stuck in the sand and blocked the way. A German jumped on the road and screamed that there is no passage here. Janka started to explain to him that they had no strength left. Then the German pushed a man towards the cart. There were also other volunteers and together they pushed the cart further, towards the branch track on the Warsaw West station, where the train was.

During the last days and nights, this girl carried over thirty people on the stretcher. She hardly ate or slept: there was no time. How come that she had so much strength in her? She was a sensation even to Germans who took her photographs.

They went onto the carriage. Janka told me that as she was sitting on the stairs of the carriage - these were old carriages - she looked around to check whether she would see me or Father Rostworowski somewhere. Nothing of this sort happened. They reached Pruszkow.

We came to Pruszkow camp on 2 September in the evening, and on 3 September in the afternoon we were out of it. "Ikar" and "Wisia" went to the hospital in Pruszkow. "Janka," Mrs. Faryaszewska and me - thanks to the Polish nurses - the German medical board counted us among the wounded and seriously ill, who were to be released from the camp. Polish staff tried to get passes primarily for the young people.

Our names were written down on the list of people who were to be released from the camp. I was written down as infected with tuberculosis, "Janka" with her bandaged hand, as a wounded person. I had a Kennkarte, but "Janka" did not have any papers. She left all her papers by the wounded friends and he did not get them back. There were about 30 people on each list. In this way, by a lucky turn of fate, we were free and not in a concentration camp like almost everyone from the Old Town.

Barbara Gancarczyk-Piotrowska

prepared by Maciej Janaszek-Seydlitz

translated by Katarzyna Wiktoria Klag

Copyright © 2013 Maciej Janaszek-Seydlitz. All rights reserved.