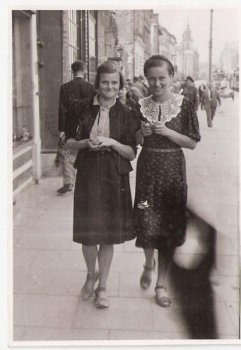

Barbara Bobrownicka as a teenager.

Interviews

Interview with Ms. Barbara Bobrownicka-Fricze The conversation with Ms. Barbara Bobrownicka-Fricze took place in the end of 2006. Its contents refers to the Memoirs, published in the section ,,Insurgent accounts of the eyewitnesses''. In the same section, the story "Our Maciek" by Ms. Barbara Bobrownicka-Fricze is published, as well.

W.W.: Could you tell us few words about yourself and your family?

B.B-F.: Tradition of fighting for the independence has always been very vivid in my family. After the fall of the September Uprising, my grand-grandfather walked to Siberia on foot.

My grandfather owned the agricultural tools factory in Warsaw, with his partner Lilpop. When the January Uprising broke out, they started to produce the weapon. After the fall of the insurgence, one of them had to run away. My granddad escaped through Zaleszczyki. I tell you one of my family's anecdotes. He [my granddad - A.R.] was waiting for a train, and a military policeman was strolling on the platform. Our family was a family of jesters and story-tellers. Granddad accosted the military policeman and started chatting. One had to wait for a train for a quite long so they had time to become friends. At one moment the policeman asked: "Sir, did you happen to know Mr. Bobrownicki?"

- "Well, certainly, I do."

- "Could you show him ?"

- "Of course!"

They were walking and looking for that Bobrownicki until my grandfather got on the train.

He left for London and was starving there, which gives evidence against Lilpop that he didn't help him. Then, my granddad participated in construction of the Suez Canal. Later on, in Paris, he was an author of many inventions, which have been deposited in the library on the St. Louis Island till today. He came back to Poland probably in 1904, when a telegram came from Paris asking my granddad to go there to put his inventions into practice, but at that time he was dead.

Another grandfather, on the distaff side, Ferdynand Borkowski, had a property near Vilnius. He ran a breeding of the race horses. When the Insurgence (in January) broke out, granddad- for my grandmother died, had two children and couldn't take part in the Uprising. The property involved four thousands acres, granddad would take care of the injured, he would hide them and provide with food. After the fall of the Uprising, the Russians seized the property and passed it to a general, who later came to my granddad and said: "Run this farm, please, I don't need this property".

After 20 years general came one more time to the Rodziewicz property and said: "Sell this property, please, because I can't vouch for my son".

People are different everywhere. Having sold the old property, my granddad bought a new one, called Todosc , near Grodno. Where did such a strange name come from? Well, Ms. Grabowska, morganatic wife of the king Stanislaw August, was very demanding and when he had bought her this country seat, he stated:

"To dosc" [which means: enough; a play on words- A.R.].

Barbara Bobrownicka as a teenager.

I was born in Debica, near Rzeszow, in the 20'th lancers' regiment, because my father, Teofil Bobrownicki-Liebchen, was its captain. He was a former legionnaire and remained devoted supporter of Pilsudki, hence, my viewpoint was the viewpoint of this particular political group. I was the first child who was born there. I spent first 5 years of my life in Debica. My father fought on the polish-bolshevik front in 1920, and then, he was a historian. He was writing the history of the war in 1920. During the war, all our hose was burned down, but my daughter found a brochure in the National Library which was a draft of the work entitled: "March from Wieprz". It's a very interesting publication. Before war, he would travel to Romania, Hungary, Bohemia and Slovakia as a journalist to launch an anti-Bolshevik campaign. The atmosphere became more and more tense and Russian kept an eye on him to the point of having arrested him in Romania, and the embassy had to get him out of trouble. He would publish the features in the "Polska Zbrojna" and deliver short speeches on the preparation to the anti-air-raid defence in the radio. He had a creative soul and would make a blunder all the time, still, he would have Wieniawa-Dlugoszewski standing on his side. They were both jokers. It wasn't beneficial for the family though. During the occupation, my father was a journalist in the Underground.

My mother graduated from the Art Academy and she was a painter. In 1920 she went to the front as a volunteer and that's where my parents met. She was a very beautiful woman, and I didn't appreciate it until I grew up. After getting married, she would stay at home and paint. All was burnt down during the war. She had a talent to make portraits. After war, after my father's death, she would make a living by making portraits, it was her passion for life. For a long while after the war I would make a living by making paper cut-outs.

Now I'm going to tell you about my brother - Jedrek. He was an extraordinary figure- the sort of Kmicic kind. I even had a letter from my friend telling that he was the most courageous person he'd ever managed to meet. To be honest, I didn't know anything about the dangers that threatened him. We wouldn't say a word so we didn't make nervous ourselves and our family. Conspiracy didn't include the external conditions only, it also included one's own family. They didn't know and it was easier: there was more peaceful.

Death of my brother took place in scandalous circumstances. It was an allied air drop near Blonie, or near Lowicz - I don't remember. Jedrek had just passed his driving test and was ordered to drive, together with a friend, a lorry with the freight from the air drop, among others, with four machine guns. He alone was armed with multi-barreled Belgian "FN" and granades. They were driving at night and at one moment they hit a German car. His commanders were driving with him on the back of the same car. It was not allowed to drive for an action with one's older commanders, who used to sit by desk! My brother governed three sections. They would never leave the dead friend, not mention the injured one.

As a result of the crash, the colleague who was sitting on a seat next to the steering wheel was killed on the spot. The Germans in the front of them were driving with dwarfed lights, they might have been smuggling something for they escaped right after the crash. My brother was injured on the road. We didn't know the course of the events. An elderly woman came to my family, to my house and told us that Jedrek was killed near Milosna and he was buried there. They not only lied but also gave the wrong place. I was living then on the Niepodleglosc Avenue. My father called me to let me know but I had an intuition and knew that my brother didn't die. It turned out that there was an accident near Blonie. I drove there with my friend Halinka Adamowiczowa and went to the local police station. And it was there where they told us about the event and that my brother was lying on the road. They had time - 17 hours - to take him from there. But those commanders, driving on the back, ran away and informed us that Jedrek was killed. I remember sitting inside of the police station, and there I spot a brown stain. So I ask:

- "Why it's so dirty in here?"

And they reply:

- "It's the blood of your brother".

- "And you didn't even give him a pillow?"

Then they gave an address of the doctor who had come to him. That doctor recognized me straight away because we looked very similar. He told me that the Germans came and took Jedrek to the isolation ward in Pruszkow. So I went with Halinka to Pruszkow, but he'd been already gone.

From the left side: Halina Adamowiczowa, Irka Czechowska (she died together with Maria Bobrownicka in the Warsaw Uprising in the vicinity of the Gdanski Train Station), Danuta Mancewicz, Barbara Bobrownicka, Andrzej Englert.

In the end, we went to two places, the name of the second one I can't remember, and he was taken away from each of them. The Germans knew that they caught a very important person - they had discovered the freight in the car- and they were looking for the isolation ward for him. But they didn't know his real name for he had faked documents with him under the name of Andrzej Jastrzebowski.

He was found in the Pawiak [German Nazi's main prison in Warsaw- A.R.] after three weeks. He had a head injury and they tried to cure it. Jedrek was so strong that he recovered from that. It would have been better for him if he head died there. Stasio Sosabowski tried to rescue him. And Halinka came up with the idea that we could send to The Pawiak germs of the typhus. The Germans were afraid of the typhus very much. The plan was that when he was to be transported to the hospital by the Germans, his friends from Kedyw would liberate him. It was December 1943. So Halinka went to the chemical baths, collected fleas and took them to the hospital for people infected with typhus. She took the fleas in a test-tube to place them on the body of the person suffering from typhus, and those infected fleas were to be delivered to the prison to Jedrek. But the prison guard couldn't get to him. And the test-tube was wasted. Halinka went to the hospital again and we prepared the next portion of the infected fleas. We lived then on the Wojsko Avenue. I had nothing to eat. I went to buy a biscuit, which cost 20 grosze. In this patisserie laid "gadzinowka" [Nazi German Propaganda newspaper- A.R.]. And inside of the newspaper I found a list of the people executed on the Leszno Street, among whom was my brother, under the faked name- as I had mentioned earlier - of Andrzej Jastrzebowski.

A friend of mine who was the witness of the execution told me that Jedrek kicked the German who wanted to hang him. This place is in the front of the court houses.

This is a story of my brother, as far as my sister is concerned - Maria - she died in the Uprising. She was 18 and worked as a nurse. I came to the Stare Miasto too late to protect her, because she wasn't afraid of anything.

But she wouldn't listen to me as I was 3 years older than her. A commandant ordered her to go to the Zoliborz and there's been no news of him since then. She could have been killed, with both her friends, in the vicinity of the Gdanski Rail Station.

Barbara Bobrownicka with her sister Maria. The photo was taken on the Nowy Swiat during the occupation.

W.W.: In the photograph replicated below there's you accompanied by your brother Jedrek and Danuta Mancewicz. You've already told us about your brother, could you tell us now something about your long-life friend?

B.B-F.: We've been friends for 64 years now. We met for the first time even before the Uprising. An actor Henry Ladosz was running a club under the auspices of the RGO, where he was dealing with the cultural development of the young and we met there. It was Danuta Mancewicz who drew me into the conspiracy. When she asked me to join the conspiracy, I was terrified - but I was ashamed of admitting it. During the fourth convention in the Zoliborz I took my vow and experienced a strange feeling - as if all of the fears had vanished, I felt physical disappearance of the fear after having taken this vow. It's a strange story. I wasn't afraid later on, although I would go through various "adventures" during the occupation. We both managed to survive. Danusia was in the only troop who had managed to push its way through going on the ground [and not in the drains as the rest of the people- A.R.] from the Srodmiescie, through the Saski Ogrod, by night from the 30'th to 31'st of September 1944.

Na warszawskiej ulicy podczas okupacji.

In a Warsaw street during the occupation. Barbara Bobrownicka (on the right side of the photo) in the company of Danuta Mancewicz and brother Jedrzej

W.W.: What were you dealing with- apart form the conspiracy- during the occupation?

B.B-F.: In the beginning I was fascinated by the literature, but I changed my interests and went to professor Kotarbinski to study philosophy. When Kotarbinski had to hide himself my philosophy was also finished. I wanted to have a broaden mind so I started to attend the underground school of politics. I passed my matura exam first. I didn't want to be a politician though.

W.W.:What kind of attitude did you have while taking part in the Uprising?

B.B-F.: I was over the moon- it was something wonderful! I didn't think then if the Insurgence would be successful: my thought didn't reach that far. I saw German soldiers, as they were walking as the defeated ones, all of them bandages-ridden. I was 22 and so inexperienced. I didn't see the signs that the Germans were not defeated yet. I had so much work to do. I had to alarm so many people. I would pull up my heavy bike on the fourth floor and inform. I would let them know to take food for three days, because the Insurgence was to be over in three days.

W.W.: How did you react to the news of cancelling the alarm for the Insurgence?

B.B-F.: We were left speechless, even enraged- for it was a terrible disclosure. All of the people would take their food in packages. Everybody could see that. I remember this feeling of amazement, when it turned out that this and that one were together with us in conspiracy, that there was our neighbour as well, that were so many of us...

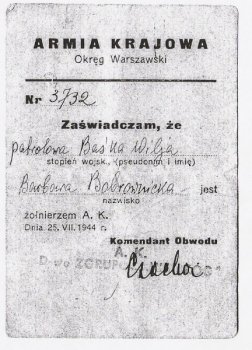

The identification card of the Home Army soldier, issued to Barbara Bobrownicka a few days before the Insurgence's outbreak.

W.W.: What did you remember from the first days of the Uprising?

B.B-F.: I start with the explanation that The Uprising for me began in the Srodmiescie. My troop was assigned from the very beginning to the Starowka, but woman doctor Joanna had borrowed me from the Srodmiescie just because she liked me. I remember her: bright blonde, smiling. She was a good person. We took an instant liking to each other. I was thinking about her as if she's been my real mother. She took me because I could create a good atmosphere; I was a sort of jester. She thought that I would stay with her to the end of the Uprising. She didn't know then that she would die after few days.

I remember the moment of hanging out the white and red flag on the Prudential. Boys took off the German flag first. I remember the fury with which they were trampling on it. We decided to use it for making the armbands. All of the girls with this armband made of the German flag, except for me, died. I can't say that it brought me bed luck. Later on, after the Starowka, I came back to the Srodmiescie, I found my grave. Then I was told that I would live very long.

I began my Uprising on the Dabrowski Square 2/4. I was witnessing the first attack on the Pasta, a very bad one, tragic. We started this attack very lately. They were sniping at us as to the ducks. The street nearby was very narrow and our boys were lying or sitting in the gates, and we would go and gather them on the sound of their moans. We were cringed for everything was under fire.

Our sanitary post in the Srodmiescie was placed on the Dabrowski Square, under the number 2/4. It was a high, eight-storied house in the shape of a quadrilateral. Volksdeutsch [the Polish people with German roots - A.R.] had been imprisoned here before they ran away and alarmed the Germans. The Germans dropped bombs very precisely from the plane.

All collapsed. All of my 24 friends altogether with my woman doctor Joanna were killed. My armband was found there; that's why they figured out that I was killed as ell. And then my grave, of which I've already mentioned, was set.

I was there when everything was knocking down. The water wires were torn and my friends, injured, were drowning and wanted me to rescue them, pull them out but I couldn't. I was so terrified! Anyway, how could I possibly rescue them when all was knocked down there, in the basement? I went out of the basement and saw the stairs. I was thinking about the stairs, that they were there and they are not collapsing. It was then when I understood that the hair could stand on end, not only in the literature! It's really possible to feel how the hair stands on end out of terror.

Later on, when I was left alone because my troop had died as a whole, we were told to go to the PKO. They told us to go to a shelter. And I personally wouldn't have gone to any shelter for all the tea in China! And I heard out of the blue: "Starowka"! There was my original troop and my sister was there as well. I went to the Starowka.

W.W.: Which day was that?

B.B-F.: It must have been before 5'th or 6'th of September, there was still a link between the Srodmiescie and the Starowka.

W.W.: What were the most important stages of your fight and work in Starowka?

B.B-F.: In the beginning I felt guilty that I abandoned this busy section, which was Srodmiescie. First days in Starowka were peaceful, but when the German attack began, it was rapid and massive right away. I was in the group "Rog" and my company had a number 101. Lieutenant "Szczerba" - Zygmunt Blisiewicz, actor from Vilnius, was a commander of our platoon. Later, in Germany, he committed suicide.

I'm filled with admiration for those boys, so courageous and noble. In my company there were people already experienced in fight. They stemmed from different districts. By the way, it was a good idea to tell us apart for it must have been impossible to put up with it otherwise.

Colleagues of Brabara Bobrownicka from the 101'st company. The photo was taken in the Srodmiescie by Sylwester Braun, in the end of September 1944.

Relations in my troop were excellent. There was only one person teasing me- my commandant- but it was because of me - I refused to obey an order to pass to the Kilinski Street and I called her a coward. The thing was that if I had obeyed her order and left the Rynek, I would not have managed to provide a first aid in time, going from the Kilinski Street. I remained in the vicinity of the Rynek and the Cathedral to the end of the Insurgence. I was a sentry there. Officially, I was subjected to the mentioned commandant but in reality I staid with the 101'st company and I worked for them. We did an awful lot of things for the civilians.

We represented the only sentry there, in the vicinity of the Rynek of the Stare Miasto.

I'm going back to your question that is the most crucial stages of my stay in the Starowka. I went through the first baptism of fire on the Starowka even before the 13'th of September, the memorable date of a tank's explosion on the Kilinskiego Street.

It was then when the first air-raid on the Starowka took place. On the Piwna Street the bombs fell down and knocked down the houses. I remember this resonant laud voice: "Nurses!!!". It was yet before launching the main assault against the Starowka.

What I went through then, on the Piwna Street, was my baptism of fire. I was on patrol and hit the spot altogether with my girls. I saw mothers running around; mad out of despair, for there were their covered children. Our boys tried to remove the rubble, but for me it was too slow. At on moment I felt that this situation made me crazy. And suddenly something strange happened to me; I was transformed into completely new human being. I was overwhelmed by some kind of peace.

W.W.: Was this transformation for good?

B.B-F.: Yes. It was then when I became a soldier. I wasn't prepared to be a soldier then. I would give valerian to those desperate women. What else could I've done? We were transporting the injured. It was the first moment. Soon after the bombardment took place, the Germans launched their attack on the Starowka.

W.W.: The next crucial event must have been the explosion of the tank on the Kilinski Street on the 13'th of August?

B.B-F.: I had a sanitary post at the Baryczka's house, under 2. I can see that moving tank till today, a kind of Russian tankietka. This tank was seized by our company. I remember the frenzy of joy. The colleagues shouted at me to join them. I was going to do that instantly, but how could I've left my girls? I was on patrol after all.

An amazing situation happened while the tank was passing by: it was probably passing through the Waski Dunaj Street and people removed the barricade, but in such a way as if somebody had blown it out! The tank passed by and the barricade was set again in its former place. After this I came back to my quarters. In one moment I heard and felt a huge detonation. We'd been already used to various kinds of missiles, to the tank destroyers and armed trains. By their sounds we would discern their types. I'm going out and I can see a huge fume. We take the stretcher because something must have happened. We're walking. While hitting the spot we see plenty of people, the pile of hands and legs. Human hands. Blood and children: killed or injured. Everything's mixed. In the moment of explosion many people gathered there to listen to a radio programme form London under a loudspeaker. I wasn't there only by accident. There were torn off hands hanging from the storeys. I saw how boys went mad and started to collect heads into the bags and took them away. And this smell of blood and plaster mixed together- unendurable! It was horrible. Krzywa Latarnia's hospital housed many injured people. Physicians were operating while there was a queue of lying people outside. We would place people in the queue. We didn't know if they were still alive. I remember unconscious little girl, she might have been alive, she didn't say a word. Physicians would operate these people in the candles' light and would faint because of overwork.

We were coming back having become absent-minded from the odour of the blood and the surplus of emotions. At one moment we see a boy: he is walking down the street and singing- he's drunk. "Such a misery- and you got drunk"- I said to him.

- "Because I was driving that tank and went for a coffee for a moment".

It was his destiny: It was only he who came out of this tank and his all colleagues died.

I have to confess that it was known earlier whose people were doomed to die. I remember my colleague, who used to come to our sanitary post and talk about his family, mother. I knew it then that it was his end. I had such a premonition which turned out to be true for I had many similar cases like that one. I remember tall Jurek from the Marymont, blonde, who used to tell a story about how his mother would work very hard so he could finish his studies. When I saw him telling about returning home I knew that he's going to die.

I knew it - unlike my brother Jedrek, who already in 1940 foretold that he's not going to survive the war- that I was going to make it and all of my family knew it.

And the story with this Jedrek was as follows. The Germans were shelling their way into the Brzozowa Street from the Praga and they were shooting at individuals using cannons. They call us and inform that there are 5 injured. Jurek, the one who was there, didn't tell us that we're under the fire. I'm leading the patrol and something touched me suddenly and I say: "Run!"

I don't know why I said that. The missile threw us on the stairs, and I was rescued by a metaphysical warning. I came to the spot afterwards. 5 boys were walking in front of us, with Jurek among them. He was lying on a table with intestines outside his body.

W.W.: Later on, to the very end of your stay on the Starowka, you were fighting in the vicinity of the Rynek and St. John's Cathedral?

B.B-F.: Yes. There were incredible people who one doesn't know anything about. I've already mentioned our commander Zbigniew Blisiewicz, who was a Vilnius actor. He was an amazing man. I can omit the civilians. We speak to little about them. We were lucky because we were in the action, we didn't have time to be scared, and they were sitting in a basement. On the Starowka, the basements had thick walls and children were born there. It was there where the son of my friend was born, and he became deaf from the bomb's explosion. It's not talked about enough. There was no light, no water. I was a nurse and at the same time didn't have the water to wash my hands. It's just incredible to imagine. I didn't cause any infection. Besides as an assistant nurse, I was carrying people to the hospital and they had to keep on dealing with it. My role was to give first aid.

We were extinguishing the fire in the Cathedral. We did it in the first place because then we set fire to it. I went through terrible experience on the Jezuicka Street. I've always been a bookworm and it was there where I saw burning rarities. Those books were 300-400 old and we couldn't save them.

Another story. I had a friend Basia Rankowska who passed the final exam with me. She was stunningly beautiful. She was known for her radiating beauty. Basie went to the Cathedral. She wanted to see a sculpture, but it turned out that it was a German and he shot at her belly. She found herself in the hospital. There's a book "Physicians' accounts from the Uprising''- I recommend it.

Doctor Kujawski describes Basia's stay in the hospital. She's just undergone the operation and her fiancé came with compote to visit her. He gave it to her and she died afterwards. This man, when realized that it was apparently him who killed her (she would have died anyway but it was a direct cause of her death) rushed into the Cathedral and was killed on the spot by the Germans. It was a kind of suicide on his part.

W.W.: How would you react to the view of people's suffering who couldn't be helped very often while the insurgent hospitals were located in the basements deprived of the electricity and medication aids?

B.B-F.: .: I was an assistant nurse, not a nurse. My role was for example to stop the blooding and carry somebody to the hospital. In this respect I had all means to do my job. Physicians and nurses were those in a worse situation, because they had to take care of patients working in the candles' light, not having in many cases adequate means or conditions to rescue the injured.

One of my duties was to transport the patient, but even this wasn't at all that simple: there were rubble everywhere and one had to make his way carefully through them so as not to slip up, one had to put his leg in such a way to make his patient no harm. It was a very hard work but it was also an emotional imperative: it was our colleagues and if one can help somebody then one doesn't think of himself. A man doesn't think but act. A man is an instrument; he acts and believes that he can help. He doesn't calculate: "Maybe I'll make it". No. He rather thinks: "I'll rescue this man, I'm saving a person's life".

In many cases the wounded supported us with their attitude. I recall the case of the 17-year-old boy whose foot was smashed. A physician was cutting his fingers off without the anaesthetic. I was holding his hand. We were telling jokes. It was an incredible experience. I don't know who was suffering more. I wasn't aware of the immensity of his suffering, was I? He didn't utter a word. If they were complaining it must have been the older injured, for instance 40 years old. They would give up straight away. But our youth were amazing. I met this boy in a captive's camp in Germany, when he was travelling back to Poland, after liberation.

W.W.: I myself would be scared even to think of how I would act in such a situation.

B.B-F.: If you underwent 5-year-old training, if you were taught how to shoot, if you had friends you knew you could count on and who trusted you, you would be a different man. If such a situation were to repeat itself now, everybody would do the same thing as we did. The youth nowadays is wonderful. Honestly. They are hard working people. We were triflers. When there are some people complaining about the youth I'm willing to suffocate them myself. The more a person was mediocre himself the more mediocrity he's trying to find in other people. I have so many grandchildren and I know their friends and that's why I say: If there was a need, it would be the same or even better! Maybe partially thanks to our experience which we would pass on to them.

Present teenagers face different challenges. What was I like? I was 17 and was going to go to my first ball on the following year. I would imagine my ball dress and a dance hall where I would dance.

It was my greatest dream.

W.W.: But it doesn't differ too much from the dreams of the present teenagers. To mention only but one television show, very popular in these days ",Dance with the stars".

B.B-F.: I don't watch TV and never saw this programme. TV was so-so in the beginning, when it was black and white. Now it's completely different.

As to the ball, it didn't take place. The war broke out.

We were thinking both with Halinka (who was in the representation of our government) who would we have become if there hadn't been any war? We would talk how a man would become more "humane" in a different direction.

W.W.: Still, I think that even if the war hadn't broken out, you would have grown out of your dreams about balls.

B.B-F.: Certainly. I wanted to be a scientist. For me the science was everything. I didn't want to get married. But the emotion overcame the passion towards study.

We were brought up by the war. We were nothing more than youngsters.

W.W.: Later on, after war experiences, you wouldn't learn more in life?

B.B-F.: It was quite the contrary in my case. I was disappointed by some of my friends' behaviour. They have never grown out of the Uprising. Life is wonderful. One mustn't, even for a while, stop enjoying it. One has to fight and learn to the very end. Fight- in the first place with oneself, for one is lazy or doesn't believe in his abilities. During the Insurgence, my fight focused primarily on the fight with my weakness, with fear.

Particularly in my case, the fact that I managed to live and survived the war and the Insurgence. I try to make the most of my life.

W.W.: Could you give some more examples of people's behaviours during the fights in the Starowka, those which most embedded in your memory?

B.B-F.: While we were leaving the Jezuicka Street, which I'd already mentioned about (when rarities were burning), when we had to set houses on fire so the Germans didn't have access to us. There was so few of us that we couldn't defend ourselves in other way. Brother of Basia Rankowska, the one who had died, announced "Szczerba" that he would set his own house ,on the Brzozowa Street, on fire. Then two elderly people came. They seemed very old to me at that moment, but they were younger than I am now. They were poor, tiny and they say to our lieutenant "Szczerba":

- "Why do you want to burn our house?"

And he's explaining it to them and I see that he has tears in his eyes. He was incredibly sensitive. And the attitude of those people was no more than that:

- "If you have to burn it, do it."

One keeps in mind such moments to the end of his life.

I have another story connected with "Szczerba". They sent a group of lieutenant Leśniewski from the Kampinos Forest to support and rescue us as our number were constantly decreasing. One can't send people from the forest to the city!

W.W.: They weren't accustomed to such conditions?

B.B-F.: Exactly. That's the reason why lieutenant Lesniewski was drinking. There was an action of the Germans at one moment. Our lieutenant "Szczerba didn't want to let Lesniewski's troop move into action. But the latter would quarrel with him, he envisioned himself as a hero, and so on. ,,Szczerba" yielded and permitted him to take part in the action. And the first bullet killed Lesniewski as he leant out of the wall. The man was inebriated and his people hurt "Szczerba" so much: they simply accused him of being guilty of their commandant's death!. But I remember perfectly how "Szczerba" didn't let him go. Fights in the forest differed from those in the city. I haven't seen people of Lesniewski afterwards.

W.W.: Results of the shooting among built-up area must have been multiplied?

B.B-F.: But on the other hand the structure of the Starowka gave a shelter. The Germans was dropping "szafy" (a kind of missile-A.R). I had my sanitary post under number two: on the Market of the Stare Miasto. "Szafy" were being dropped towards our direction. There were terrible gusts. Each time they passed, the missiles would destroy everything and we had to scrub the floor so it was clean. Then, there were next ones. Once there was a missile which passed unnoticed. Suddenly, the four of us found ourselves locked in the Ladies. We didn't even know how we made our way into it because each of us was in a different place before. I was standing together with my friends behind the slammed doors and thinking: "What if it's not going to open?'' But finally it did. We resolved not no clean the floor again and after that no "szafa" played again. This floor brought us bad luck.

W.W.:The Starowka used to be referred to as "hell". A quotation from the Padlewski's book can be cited: "March through the hell". What was, in your opinion, the Starowka's hell characterized by?

B.B-F.: I can't describe it as "hell". It was particular events. It was daily work. I felt that we were needed. I knew why we were doing it and I didn't treat it as hell. I treated it as fight and duty. Joy that we would liberate ourselves and finally get rid the Germans. As I've already told, the tradition of fight for the independence had been present in my home for generations. I grew up in that kind of atmosphere.

W.W.: So it was possible to get used to those conditions. A man wasn't scared all the time?

B.B-F.: I'll tell something very strange. We would feel very safe there. I didn't feel I was in danger despite the awareness that there are only few of us and we were left alone. I knew every nook and cranny. I knew those people. We weren't super humans. It's just a man get used to certain things.

W.W.: So the morale was kept high to the very end?

B.B-F.: Yes. We would also comfort the civilians. We were trying to help them in this awful hell they were living in, in hunger, stuffiness, gloom. The role of an assistant nurse is that she has to help, has to rescue, she can't let herself go through breakdowns. One mustn't doubt whether the thing one's doing is effective. I was comfortable with it, being a woman. There were girls who happened to shoot a gun. Thanks be to God I didn't shoot at anybody! I'm not able to imagine a person falling down after my shot.

W.W.: Could you describe your last moments on the Starowka?

B.B-F.: When we started withdrawing, from the total number of our company there were 27 boys left on the line. On the Rynek, there were two of them in each gate, and they were talking in whisper because thousands of the Germans were already there, so they mustn't have got to know that there were only 27 left while the rest of our troops were withdrawing to the drains. We were occupying the Rynek and the evening was drawing near. There was another house near the Baryczka's house; I don't know its name. One of our boys had his post there with a LKM [a kind of gun-A.R.]. He was targeting at all corners so as to deceive the Germans that we were still there. And at one moment the gun broke down. He started to run away. A soldier without his gun is so defenceless. It's a shock to him. It's not an accusation on my part. So I'm running away among those ruins too. And I had a sanitary bag with me as the last one left in this area. All of the girls had gone to the Kilinskiego Street. At one point I realized that there were those twenty-odd boys. In the meantime, the Rynek was already filled with green German uniforms.

I threw my bag and start running to the Krzywe Kolo Street. An AL troop [the Public Army- another type of the troops - A.R.] was deployed there. I tell their lieutenant to give me few people, because we have to shoot as our boys are there. He delegated three of them with guns. I was coming back with them. And once again my hair would stand on end with fear, but I knew that if I had moved back they would have escaped. Fear is a horrible thing! But it has to be kept under control. I located each of them in a separate window. Once they started shooting the Germans fell into a panic. They might have supposed that we had set up an ambush. And so they were running away, many of them got killed - my joy- I'm ashamed of it. German soldiers must have been so tensed, they didn't see anything, and they must have been scared. One of them was killed while sitting on the planks. There was so green with dead German soldiers' green uniforms. I've felt ashamed to this day that I was so happy then. I began shouting madly that there were no Germans finally! We were there together: AK [the Home Army - A.R.] and AL [the Public Army - A.R.]. There were no bad relations between us.

W.W.: It was you who were in command of this counter-attack because you placed those boys from the AL on the shooting posts.

B.B-F.: We can say that because our lieutenant wasn't around; he attended a meeting. His second-in-command came and said that I'm the person in command and he walked away.

After this event I had another story connected with the Baryczka's apartment house. I sad that there was no water on the Starowka and being an assistant nurse I couldn't wash my hands to put a bandage on. When the previous action was over, I opened a room and found supplies of the soda water, stored up to the top of the ceiling. What an experience it was!

One more experience from the very final moments on the Starowka. We were occupying the Rynek area all the time for the sake of the evacuation which was being carried out through the drains. I found a pancerfaust [a type of manual grenade - A.R.]. And I think to myself: "We are withdrawing, we have to hide it just in case a child will grasp it and it will explode". I went to the ruins nearby to look for a place to hide a pancerfaust and I met a six-year-old, blue-eyed child. I can remember this boy to this day. He asks me: "Are you going away?". I said: "No". This lie and those childlike eyes have embedded in me for ever.

One more thing. When I was permitted to leave a sentry post and move towards the drain. There was such a dark night.

W.W.: There were no conflagrations - only the ruins? I've always thought that a night on the Starowka must have resembled a day, because of the huge fire.

B.B-F.: It was absolutely dark then. It happened before that when there was something burning, huge tongues of fire would pop up- it was incredibly picturesque. The Starowka was made of brick. The fire would appear only then when the planks inside would burst into flames. The walls were hardly burning but they would collapse in a "magnificent" way. A bombardment would take place and a house would split up and its walls were slowly falling down on the ground and the heap of rubble was all that was left.

While moving forward through the darkness we were holding our hands so as not to get lost. The civilians were standing on the pavements. We didn't see them but we could feel they were watching us. Suddenly one of them speaks up: "When you started you didn't ask. Now you're leaving and don't say a word either".

These were the words that would get deep down a man's heart and accompany him for years.

In the end, having nowhere to sleep, we were sleeping on the floor. I got a wonderful blanket, shaggy one. I could unfold it on the floor and it was my great friend. When I stood in front of the sewer's manhole, major ("Barry") ordered me to leave it aside. I understand that I couldn't take it but it was a tragic separation. It was lying there so lonely and I was feeling like a traitor. These things are difficult to realize!

W.W.: Were you relieved after coming down to the drains? For some of the Uprisers it was a relief for they felt more secure than on the surface, where there were shots etc...

B.B-F.: .: I was not afraid of the shots, because, as I've already mentioned, I knew that I wouldn't die. I got scared a lot occasionally, I've already talked about it. I was scared of the basements, that I would be covered; this is what I was scared of.

While we were making our way through the drains, everybody was so exhausted that it seemed to us that we would never make it. At one point a helmet belonging to my friend Wojtek Wronski (future president of Toronto) fell down to this dirt. He was so wearied that he put it up and put it again on his head with all that it contained. Next moment he started to swear so badly that it made us laugh. We forgot about the silence that was obligatory in a sewer.

Our drains from the Starowka were not the same as those from the Wajda's movie. We were holding hands. The waste reached our ankles. The march was very wearisome and there came a moment when I wanted to lay down in the drain and didn't move on. I didn't care then but on second thought of everybody walking over me I decided not to do it. We were so powerless!

They were drawing us from the sewer near the Warecka Street. We couldn't get out unaided. First impression was: the houses are standing and there's light! They would place us on a straw; we were disgusting and smelly. They treated us with the lentil soup or something similar. On the following day there was no more food and one could hear that "The Starowka is robbing!". We had to eat something anyway.

Then, the scenery of the Srodmiescie was different, the people were also different. I heard someone's voice:

- "They will come for us now when you've come here!"

They thought that it was us who were attracting the Germans to come to their place! Our fight didn't matter to them.

We were lying on the concrete floor and couldn't wash ourselves. In the beginning we got a soup plate of lentil soup, and since that nothing more. They accommodated us out of mere duty. There was no kindness, no common language.

This was how the contrasts between the Starowka and the Srodmiescie looked like. Yet, later on, after the bombardments and the fights at the beginning of September, the Srodmiescie looked similar to the Starowka. It was those exhausted and bleeding troops from the Starowka who played a big role in the defense of the Srodmiescie, after the Starowka's fall.

W.W.: Could you tell us what happened to you later on, on the Srodmiescie?

B.B-F.: We went to the Savoy Hotel, but we had to leave it as the Germans were firing shells from the "szafy" and we moved to the conservatory.

I went then to the Kopernik Street where our commandant's sister was. There were beautiful books on the third or fourth floor. I immersed myself in those books and forgot about the whole world; and it was just then when the house was bombarded. When I gained consciousness it turned out that I'm lying on the threshold with an abyss below me. The whole house was knocked down and I didn't know how I found myself there, on this threshold, under the abyss. I might have been thrown there by the gusts of explosion. I was lying there not knowing what to do. I was afraid to move. At a point I heard the following conversation coming from the yard:

- "I'll go for her!"

He's being advised against going there for the house might collapse at any moment. However, he went upstairs for me. I was so "rude" that I fainted. I have no idea how this boy managed to carry me down. He was told to have had bleeding hands. Unconscious man is far heavier. I'd never seen this boy before; I didn't even know his name. Once I opened my eyes, I found myself lying on the dog's bed and a big animal was standing under me- a great Dane with such a wise eyes. And he's staring at me. I was looking at him and he was looking at me. Nobody was in apart from me and this dog.

W.W.: Talking about the Starowka, you were giving examples of interpersonal solidarity. In this case we have an example of the solidarity between man and dog. Pigeons on the Starowka, described by you in the story entitled: "Our Maciek", were another example of this kind of solidarity.

B.B-F.: I described it because for me it was an example of a great friendship and symbiosis. Those poor pigeons didn't know about my existence but I knew them. I saw those horrible planes and tried to compare them with those weak wings of a pigeon. I don't know what those poor birds would eat there? We had already run out of food ages ago.

W.W.: Was anybody hunting them?

B.B-F.: No.

W.W.: I've read somewhere that the pigeons on the Srodmiescie used to be trapped and killed for food.

B.B-F.: I can't imagine anybody on the Starowka eating a pigeon. But after that, on the Srodmiescie, our boys would eat dogs, and what the latter could have possibly eaten? It must have been only dead bodies. But I'll tell about a dog later.

W.W.: Maybe there was better food on the Starowka?

B.B-F.: Some of us would store the food on the side. Soda water which was found by me on the last day on the Starowka, came from this kinds of supplies. It got wasted. We had no time to make use of it.

To be honest we didn't even have time to provide for food. When I look back I'm surprised that we've survived. But even later, in the camp, the situation was far worse and we made it anyway.

There was a time when there was nothing to eat. One had to eat lump sugar all day long. One can come to hate lump sugar when it's the only thing to eat.

Now I'm going back to the further course of my experiences on the Srodmiescie. Somebody took me from the dog bed because I had a knee injury and I went with him to the conservatory. There my friends tell me: "Don't come here for there's going to be a bombardment". It had always been like that that the bombs were dropped wherever I was. I knew that the planes were "following" me. Indeed, they appeared immediately and set the conservatory's building on fire. Two of our friends were inside one of the rooms (a boy and a girl). They were knocking and banging to release them but we couldn't do anything because of the fire. It was then when Wojtek Wronski wanted to shoot himself but some people snatched the gun out of his hand. They must have burnt alive there. We couldn't do anything to rescue them. And we went away and they had to remain there.

Then I took a rest for a week - I had a knee injury - on the Srodmiescie Poludnie, at my aunt who had polished floors. In the meantime, the Germans seized the Powisle and were violently attacking the Srodmiescie. I came back to my troop when the biggest fights were over. I was together with my colleagues at Jablkowscy Brothers at the Main Post Office.

Barbara Bobrownicka (by the boiler) is cooking the corn flour soup for her colleagues. Vicinity of the Main Post Office. Photo: Sylwester Braun.

The following event happened to me there.

Ceasefire lasted three days. During this time, German soldiers would visit us; they were basically boys. They were so nice, we had a great conversation. How perfectly we understood each other! After three days, we started to shoot at each other again. One of them told us about an assistant nurse or a liaison soldier, with an armband, and he couldn't, he didn't want to shoot at her. I watched his helpless face and I remember this man till today. I saw for the first time that a German could be a human being.

Another characteristic event from this period. I was coming back from the Srodmiescie Poludnie to the Srodmiescie Polnoc. People, the civilians, were walking ahead of me. They were carrying the sacks with wheat- you couldn't see a man, only this sack covering his legs. Somebody turned to me at a point and said: "It's your fault!", because I had an armband.

Barbara Bobrownicka with her colleagues from the Starowka on the military post at the Main Post Office. Photo: Sylwester Braun.

W.W.: Were you wearing ,,panterka"? [military uniform - A.R.]

B.B-F.: I wasn't wearing panterka, I wasn't so privileged. I was wearing my cousin's jacket. The Uprising was supposed to last for three days when I was going to take part in it in September...

And those people put their sacks on the ground and move towards me. Their eyes are terrifying! I'm pushing my way to the wall and feel that it's over for me in a moment. Suddenly a voice spoke up:

- "People, what has this girl done to you?".

They pulled themselves together and came back to their sacks, put them on their backs and move on. It happened in the end of September, ten days before the fall of the Uprising. When I came back, we were located near Bracka Street or on the very Bracka Street - Jablkowscy Brothers. The boys suggested "Let's eat a dog!" . And I replied: "No! For me a dog has a soul and I'm not going to eat a dog!".

Later on, they would do something like that: they would sit on the couch and start barking when I would come around and say that they had two souls. At that moment I told them: ,,What? Do you think I'm not going to eat it?".

It was quite good with the pasta.

W.W.: The moment of capitulation. Feelings. Relief? Despair?

B.B-F.: An awful feeling. I described it in my diary. First and foremost one question: ,,What have we done"?. We didn't see the rubble, those falling walls in the fervor of fight. But when everything's fallen into silence and when we could take a look around, a question came out: "What have we done?". To be honest, I'm not speaking for everybody, I'm speaking for myself. It was such a horrible despair because we were not ready for it. Capitulation is the worst thing during war. I felt sorry for the commandants who had to make this decision. I wrote more about the capitulation in my diary.

W.W.: Later on, after the capitulation, the march to Ozarow took place.

B.B-F.: It was awful because I ate the dog. I was seriously ill through the whole night. My body went on strike. The awareness that I had eaten a dog triggered my illness. I wanted to be so brave while eating this dog, and the boys were laughing at me. The dog was tasty, mixed up with the pasta found in the basement.

The march to Ozarow. The people were saying goodbye to us, were crying. We hit the spot quite lately, for it was over 30 kilometers away. And in addition, I put a lot of heavy books with thick covers into my rucksack.

W.W.: Where did you take these books from?

B.B-F.: From houses where there were no people. I remember Spinoza. Then I would gradually take those books out of my rucksack and leave them along the road. Lonely and abandoned by me! To be true, I didn't read Spinoza again.

W.W.: Could you tell us the story of the photograph reproduced above?

B.B-F.: After arriving to the camp the Germans told us to take photographs. Photos were taken by French captives. All of the girls would put on a sulky face, looking daggers at them. However, I tell these Frenchmen: "Take a normal photo so I could send it to my house". French came and I smiled; Indignation among my friends was enormous. How could I smile on the photo taken for the Germans? My name was Bobrownicka. Frenchmen sent it to the barrack with a correct name on it and all of my girls would say afterwards: "What a pity that we haven't thought about it earlier!".

I didn't want my house to suspect me of starving. I didn't want to ask for sending me brown bread either, because if they only had heard about brown bread, they would have thought that I was dying of hunger and they themselves didn't have anything to eat. I just wrote to them: "Send me colored paper, because as I was traveling by train, the workers transported to the force labor would ask me: "Give us your addresses so we could write to your families". And so I wrote. The family was in Zakopane.

Somehow I didn't die of hunger and survived.

W.W.: There are no descriptions of your experiences from the captivity period in the Diary given to us?

B.B-F.: Right. I'll prepare those memories later. I can shortly outline what was happening in the first camp. It housed four nationalities. Our soldiers, Dutchmen, Frenchmen and the Belgians. They were standing behind the wires. We were walking with great difficulty. The Germans told us that there would be a camp for Polish soldiers next to it. What happened to us? We stood upright and mustered up strength. We were marching holding our heads high. They were Polish soldiers from September [1939- A.R.]. They were proud of us. Nobody had the soldiers like us- fighting girls. Frenchmen and Dutchmen (it was a Stalag, but they would be given packages) were throwing cigarettes and chocolate towards us. It was a crazy march after the Uprising. It was our victorious march past. We were so proud and didn't feel defeated at all.

We were given plank-beds with straw-mattresses when we hit the spot, as well as checked - covered blankets and quite tasty food. We were surprised that the Germans treated us in such a way. But it lasted only for three weeks. To the arrival of the Red Cross. After that, we were told to go on foot to the Bergen Belsen.

I will develop the follow-up story in the memoirs from the captivity.

W.W.: What does the Warsaw Uprising mean to you?

B.B-F.: .: It's a part of me. I'm organically bounded with it. The Insurgence made me a different person. I'm going back to this feeling on the Starowka: I felt as if some things had been reorganizing within me. It was very physical.

I hadn't been able to read about the Insurgence for 20 years directly after war. It wasn't until I started to appear on the radio when I began to plunge into the subject.

W.W.: How could you describe the people of those days?

B.B-F.: We were a united country in Warsaw. Everybody was so kind towards one another. Of course, spies, informants, blackmailers among us, but even anti-Semites would rescue the Jews. It was a spiritual revival in those circumstances, really! Only few people would cheat. For example, I can't recall my being afraid of my neighbors, acquaintances, people in a tram.

I give you an example of the atmosphere of those days.

I was traveling back from the Zoliborz to the Srodmiescie by a tram and was carrying with myself six guns. It was a heavy suitcase. Out of blue, on the viaduct near the Gdanski Railway Station, news-vendors run to us and shout: "Raid!".

All of the passengers go out or run away. I kept my suitcase under a table. I'm hesitating: ,,What am I going to do if I go out and run straightly into German hands!". The Germans haven't appeared on the horizon yet and the conductor comes near me. He says: "On the Narutowicz Square in 45 minutes".

He took the suitcase away from me and put it into some sand in a tram, into a box and drove away. I rush into the Gdanski Railway Station. I've got no money- I never had money- rickshaw men stand nearby and I talk to one of them: "Excuse me, Sir, I've got no money but I have to be on the Narutowicz Square in 45 minutes".

"Get in, please". - He took me to the place for free. I drove to the Narutowicz Square which is plenty of trams; how can I find the right one? I realized that I don't know how the conductor looked like, and the guns were highly valuable during the occupation. When I'm standing so helpless, a conductor comes to me, brings my suitcase and gives it back to me. How we trusted each other those days!

The photo of Barbara Bobrownicka taken during her duty in the YMCA, shortly after the end of the war.

W.W.: Thank you for the conversation and for giving us the Diary, thank you for the stories and for the preparation of the memoirs from the captivity which significantly enrich our collections.

Interview conducted by Wojciech Włodarczyk

Edited by: Maciej Janaszek-Seydlitz

Translation: Anna Rewekant

Copyright © 2010 SPPW1944. All rights reserved.